The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

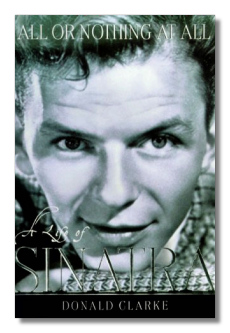

All or Nothing at All

A Life of Sinatra

Donald Clarke

New York: Fromm International

Originally published 1997. 290 pp

ISBN: 0880642246.

A friend of mine, now in his eighties, once remarked sadly, "Everything passes. Even Gershwin." The great age of American popular songwriters has gone, and we are left mainly with the witless and the self-indulgent. Arthur Schwartz, Harry Warren, and Burton Lane are, to most, names only, and the jazz-influenced harmonies of these men lie quite beyond the range of most of today's current successes. The music from roughly the Twenties to the Fifties became the bedrock of Sinatra's repertoire, and no one sang it better. As it became classic, so did he.

As the plays of Sophocles did for Aristotle, the classic invites us to make a definitive statement. Sinatra resists this kind of pinning down. In a sense, he is too many things to too many people. Mel Tormé, no slouch himself in Sinatra's artistic territory, called him "the voice of our time." To those of a certain age, Sinatra was simply The Voice. Tony Bennett realized early on in his career that Sinatra had made things difficult for other male pop singers. Once Sinatra had recorded a song, finding an alternate, individual interpretation an audience would accept took a great deal of work. To paraphrase the critic Gene Lees, if you didn't sing it like Sinatra, you sounded as if you were singing it wrong. If Sinatra were only the best male pop singer of his time, that would be something, but, as Clarke points out, Sinatra became central to the culture – even an icon. For a certain generation, he epitomized hip and cool, even though his personal life ran often at violent odds with the image. One can argue that a truly hip and cool guy doesn't punch out or have beaten up people who can't fight back. After the early Sixties, hip and cool moved away from Sinatra toward people like John Lennon, which must have really burned Sinatra up. On the other hand, a lot of high-profile rockers – from Jim Morrison to Elvis Costello – openly admired Sinatra's singing, as well they should.

Clarke's usual virtues (he has written on the pop music business and a bio of Billie Holiday, as well as edited The Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music) are abundant. He comes up with individual observations remarkably at the heart of the matter. He takes us on a breathtaking tour of pop music from the beginning of the Twentieth Century and tells us why American pop differs from its European counterpart. Also, without getting dauntingly technical, Clarke puts across what was so extraordinary about Sinatra's singing. In the field of pop (as opposed to jazz), Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire are probably the real revolutionaries. They laid down the ground rules for what to do with a microphone, but neither had Sinatra's impact. Astaire simply never had the pipes, although he had everything else. Crosby wasn't a repertory singer the way Sinatra was. He made a great deal of money even with a great deal of schlock, and he had about twenty good years. Sinatra went on and on, to a great extent revisiting the same songs but with new insight, and touched the culture more palpably. I don't want to give anything away, so you'll have to read Clarke for yourself.

Clarke also refers to Sinatra's messed-up, highly self-destructive personal life, but don't expect a tell-all. Clearly Sinatra's psyche doesn't interest Clarke as much as the answer to why so many of us let Old Blue Eyes act out so often. How Sinatra got inside of us is the grail Clarke pursues. Clarke shows Sinatra at the center of changes in the music business and as a representative of the postwar era. This thread alone is worth the price of the book, and very few people other than Clarke could have pulled it off.

We still need a technical book on Sinatra's singing, one that would benefit not only pop singers, but classically trained singers as well. Sinatra phrased with great acuity of meaning, which means he understood intellectually and emotionally his texts and could find the convincing musical expression of that meaning. Although as he grew older, he could no longer sustain the long lines that had made him famous, he still found ways – much as Mabel Mercer did – to make wonderful music, as in his late, hard-swinging rendition of Kern's "The Way You Look Tonight." His failures mainly had to do with choosing songs far from his style and ideal point of view – essentially urban, emotionally sophisticated, and tinged with jazz. Folk music, however beautiful, was beyond him. His attempts to find new songs, although he had a number of hits, weren't always successful. Even he hated "Strangers in the Night," although (as Clarke points out) this leaves the puzzle of why he recorded it at all. "L. A. Is My Lady" is even worse, and the Cycles, Duets (both volumes), and Trilogy albums (or substantial parts of them) crashed and burned. This to me is the saddest part of Clarke's story. Sinatra regarded himself as a singer of current songs, but with few exceptions current songs weren't right for him. The heart of his music, by the time he stopped performing, was forty to seventy years old. On the other hand, that heart was extraordinarily strong, and no one has yet supplanted Sinatra's musical pre-eminence.

Copyright © 2001 by Steve Schwartz