The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

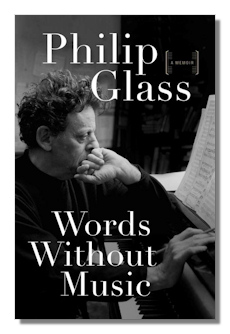

Words Wihout Music

A Memoir

Philip Glass

Liveright Publishing Company, 2015. 416 pages

ISBN-10: 0871404389

ISBN-13: 978-0871404381 (hardcover)

One day in the 1990s, a young man from the cultural division of the U.S. embassy in Paris handed Philip Glass some letters. They had been written long before by the eminent teacher Nadia Boulanger, in an attempt to get Glass' Fulbright fellowship renewed. What she wrote astonished Glass, who had not considered himself one of her most gifted students. She said, "I have been working with Mr. Philip Glass on musical technique. My impression is that he is a very unusual person, and I believe that someday he will do something very important in the world of music."

She was right. Glass, along with others, has made a difference in the history of musical style.

Glass had worked very hard with Boulanger, following his studies at Juilliard, to master the harmony and counterpoint basic to the tonal music Glass had decided in the course of his studies he preferred to twelve-tone and dodecaphonic music, even though he also appreciated much of it, particularly that of Berg. He found that Boulanger could be quite a terror. One day, for instance, after being reassured about his physical and mental health, she wheeled around and asked how he could account for the presence of a parallel fifth in one of his exercises. Something I had often heard about, but never understood, was the ancient taboo against "parallel fifths." Glass explains this concisely; the point of counterpoint is making different melodic lines distinctly heard, but the same fifth interval in two melodic lines make the lines audibly indistinguishable. My reaction to this: why didn't anyone say this before?

Besides giving Glass a more total grasp on what he was doing harmonically, I see an influence on his use of rhythm, coming from his study of Bach with Boulanger. There is a strong baroque element in the relentless rhythmic pulse characteristic of much of his music.

It was learning from another review that Glass had been one of Boulanger's students in Paris that moved me to acquire and read this book. Most of the composers I wrote about in my book, Neoclassical Music in America, studied with Boulanger, but I had not known this about Glass. He learned about Boulanger from a friend at Juilliard. After his graduation and two years writing music for public school students, he spent the following two years in Paris with Boulanger on a Fulbright fellowship he had passed up twice before being awarded one on a repeat application.

In Paris, Glass also made the acquaintance of Ravi Shankar and worked with him on music for a film. Indian music became another major influence on Glass's musical style. Alla Rakha, who worked with Shankar, and taught Glass the tamboura, identified a concern with the accents in the music Glass was recording with nine players; Shankar concurred. Rakha kept insisting "all notes are equal. " But they weren't – until Glass erased all the bar lines, revealing a stream of notes grouped into twos and threes. He turned to Rakha saying "all notes are equal, " which earned him "a warm, big smile." Glass was to work with Shankar and especially Rakha later, in New York also, gaining a "real grasp of how the rhythmic structure that was at the root of his playing shaped the outcome of an entire composition." He also learned the theory behind the music interms of music's basic elements of harmony, melody and rhythm.

In writing film music, contrary to the usual practice, Shankar insisted on seeing portions of the film before producing the music. Glass later did the same.

At the end of his time in Paris, in 1965 at the age of 28, Philip Glass married his first wife, JoAnne Akalaitis, a beautiful and brilliant theatre person. With her, after their return to New York, he had two children, whom he cherished. Philip and JoAnn worked professionally together for half a century, but the marriage ended in 1980 in consequence of a brief affair Philip had. He married again, to a woman Glass never names, but that marriage also ended in divorce, evidently not long afterwards, when meeting an artist named Candy Jernigan resulted in a very powerful mutual attraction. They had ten years together before she died of liver cancer. Glass writes movingly about her end. He says nothing about his fourth marriage, no doubt out of regard for her privacy, but he had another two children with her and he dedicates the book to his four children by name.

Meanwhile, returning to 1965, Philip and JoAnne made a journey to the East, from Paris overland to India and the Himalayas, in search of a yogi on account of of Philip Glass's strong interest in esoteric traditions: hatha yoga, Tibetan Mahayana Buddhism, Taoist quigong and tai chi; and later the Toltek tradition of central Mexico, all connected with an idea of another world. In later years, Glass once had occasion to respond to a heated attack on meat-eating by one teacher, by responding, "But Swami, I've been a vegetarian for forty years!"

Most of the foregoing is from the first half of Glass's memoir. The following two parts deal with Glass's professional and personal life in New York. He and JoAnne formed an unconventional theatrical company, Mabou Mines, and Philip founded his performing ensemble. He wrote music for Samuel Beckett's "Play." JoAnne was also very interested in Beckett. Glss became friends with many artists and poets, as well as musicians, and found immediately that they had little use for the modernist classical music of Stockhausen, Boulez or Milton Babbitt, preferring rock, actually. Glass felt that the training he had from Boulanger and Shankar had him "well equipped musically, [with] the beginnings of a new musical language...rooted in the grammar of music itself," that he could work with professionally.

Glass alternates chapters on his music and his personal life. He was acquainted with many famous people including Allan Ginsburg and is not only on a first name basic with them but even on a nickname basis. Others he mentions at various points are unknown to me. He does make vivid some of his neighbors on Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where he and a friend purchased fifty acres for summertime residence.

As Glass did not wish to pursue a teaching career he supported himself for many years with jobs as a furniture mover, plumber, assistant to the sculptor Serra, and taxi driver. JoAnne did house cleaning in addition to her theatrical work. Glass was shocked to find, following sell-out houses for his opera Einstein on the Beach in Europe and the Metropolitan Opera, that he was a hundred thousand dollars in the hole for expenses. It was not until he fully learned the difference between the musical scene and the music business that he began making money from his music. Eventually he was extremely prolific as a composer, with dozens of operas, film music, and ten symphonies plus one presently in progress. He discusses a few of them in depth. I have to confess limited acquaintance with most of his output, but I think very highly of his eighth symphony, the last two movements of which are particularly beautiful, and not what one might expect from his reputation as a "minimalist."

One of the first and last questions Glass asks about music is where it comes from. When he had put this to Ravi Shankar, at the time of their first acquaintance, Shankar told him that in his own case it came from his teacher. In Glass' final chapter he writes about his own creativity, saying that he does not think about it in the process of writing. He says, "I'm not thinking about music, I'm thinking music. My brain thinks music. It doesn't think words…. I have to find music to go with the image or music to go with the words. And I have to find the music from music itself."

I found this book riveting. From the opening chapters about his parents and early life it is vividly written. In the way it kept my excited attention it takes its place besides the wonderful autobiographies by Frank Lloyd Wright and Bertrand Russell. I recommend it highly – both for its illumination of Glass' career and for his personal revelations about his life and outlook.

Copyright © 2015, R. James Tobin