The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

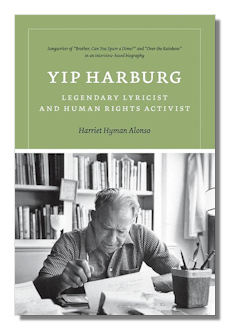

Yip Harburg

Legendary Lyricist and Human Rights Activist

Harriet Hyman Alonso

Wesleyan University Press. 2012.

305 pp.

ISBN-10: 0819571288

ISBN-13: 978-0819571281

Summary for the Busy Executive: Less than grandish.

This book combines a biography of lyricist E.Y. Harburg with a mainly political analysis of his shows and songs. Probably the most technically accomplished lyricist of his generation – which included Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin, Andy Razaf, Irving Berlin, Lorenz Hart, and, a little later, Johnny Mercer – Harburg had a leftist, although not Marxist, social point of view.

Born into grinding poverty, E. Y. Harburg (né Isadore Hochberg and known as "Yip") lived with his immigrant parents in the tenements of New York's Lower East Side. His parents worked in the garment-industry sweatshops, and their Yiddishkeit socialism informed his own view of the world. His older brother, Max, described by Harburg as brilliant, climbed out of the dirt to become a first-rate physicist and mathematician (he also earned a law degree). None of the family, including Yip, knew exactly how he did it, other than through brains and hard work. Max, however, died of cancer at 28. At that point, Harburg lost his faith and his belief in an active, caring, even existent God.

Harburg entered a scholarship program the City of New York had made available by competitive examination. He claimed that studying for that exam was the hardest work he ever did in his life, but passing it paid off. It not only got him into the best public high school in the city, but guaranteed him free tuition at City College. After a successful corporate career, he built up a thriving business in electrical supply during the Twenties and lost it all in the Crash. At that point and with the encouragement of his former schoolmate Ira Gershwin, he decided to give up, as he put it, the fool's gold and fairy dust of business for the solid realities of song writing.

You can find the main outlines of Harburg's life in Who Put the Rainbow in the Wizard of Oz by Harold Meyerson, Ernie Harburg (Yip's son), and Arthur Pearlman. Harriet Alonso gives you more detail. As the subtitle indicates, the book slants to the political (not necessarily a bad thing), and Alonso depicts the blacklist period particularly well. She also has extensive sections on Yip's collaborators in a series of "Pauses," which, among other things, try to get inside Yip's creative working relationships. A partner like Yip was both a joy and a curse. If he liked what you did or respected you as a craftsman (mainly song composers), he made working a high. If he felt insecure in some area (playwriting or dance, for example) and couldn't picture a result, he could be downright rude.

The meat of the book lies in Alonso's discussion of major songs and major shows, always from a sociological standpoint and sometimes from a dramatic one. We get very little – almost entirely from Yip himself – on the craft of lyric writing. Furthermore, she doesn't seem to understand the sources of Yip's poetry, other than W. S. Gilbert. Harburg grew up in the age of the great newspaper columnists, particularly the panjandrum Franklin P. Adams, who published light verse from contributors. FPA, as he was known, favored the old French troubadour "trick" forms like triolet, villanelle, and rondeau, expressed in contemporary American. Getting your work, for which you were not paid, into an FPA column meant that influential theater and literary people would see it, and several contributors, including Ira Gershwin and Lorenz Hart, went on to distinguished careers. Thus, you wanted to make FPA more inclined to accept your contribution. Harburg referred to himself more than once as a troubadour. It's a distinct kind of wit found as well among the era's writers like Ira Gershwin and Dorothy Parker. However, Alonso isn't alone. I've never seen a book that discusses this in depth.

I found the book more dutiful than entertaining (unlike Meyerson and Harburg). Harburg may have wanted to "educate" an audience, but he never forgot that he also had to entertain. For all the serious issues they bring up, Bloomer Girl and Finian's Rainbow give the audience a good time. What I miss in Alonso's book is a sense of fun. I'm sure she loves Harburg's humor and isn't Seriously Earnest in her daily life, but often she treats Yip's delights like a Chomsky essay. The sheer fun of Yip, serious though it may be, doesn't often come through to me from the text.

Copyright © 2013 by Steve Schwartz.