The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

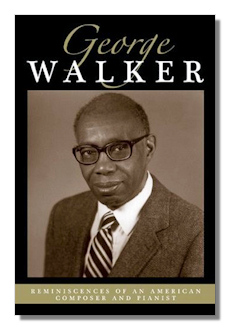

Reminiscences of an American Composer and Pianist

George Walker

Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. 2009. 230 pages.

ISBN-10: 0810869403

ISBN-13: 978-0810869400

Summary for the Busy Executive: Depressing.

The Black classical composer is as rarely glimpsed as a factual headline in the National Enquirer. Based on the little I've heard, however, I can guess they must number more than most listeners think, if they think of Black composers at all. I don't mean composers like Ellington, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Wynton Marsalis, or Charles Mingus, who inhabit a space between classical and jazz, closer to the second than to the first, but composers like William Grant Still, David Baker, Hale Smith, Roque Cordero, Olly Wilson, and of course George Walker, the first African-American composer to win a Pulitzer – and not a "special" Pulitzer, either. For some of these composers, like Smith, Baker, and Walker, I initially had no idea of their skin color. After all, I'd never heard their music in concert or saw pictures. I simply liked their work and followed what I could through recordings. And of course in the U.S., the default color is white.

Probably because of an unusual childhood, the idea of a Black classical composer wasn't strange to me anyway. Most of the Blacks I personally knew in music played or wrote concert music. If I had a bias, it was that not really understanding improvisation, I didn't think of a jazz musician as composing. When I attended college, Olly Wilson taught on the faculty, and his music didn't differ in kind from most of the rest of the composition department.

At any rate, I first came upon Walker's music on an old CRI (I think) LP: the Piano Sonata #2 and Spatials. Both struck me as tough nuts, but powerful and boldly Romantic in their very Modern way. This music grabbed you. It wanted to communicate, despite the density of the idiom. I could discern no obvious pop or jazz influence, although I later discovered that Walker sometimes embeds pop and jazz standards, often by Ellington, in his work as a kind of basic pitch-set – you really couldn't make them out through a casual listen. So here was another "difficult" Modern doing heroic work, and given the conservatism of audiences, the best of luck to him.

Consequently, I read this book with a bit of a shock. Writing in an unembellished, straight-ahead style, Walker remembers not only every triumph, but every slight, both real and fancied. Much of the book deals with how he hasn't gotten his due. He has an animus toward Gershwin, found in other Black musicians as well, and it's a can of worms I don't care to open. Nevertheless, he seems to placidly accept the Guggenheims and various other grants he's received but often attributes his turndowns to either ignorance or prejudice. I wasn't there, of course, so I have no surer way to judge, but it does seem odd to me that his critics in his accounts tend to be either drunks or racists. His dismissal of Donald Rosenberg, former critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer – an example I happen to know something about – takes very little of Rosenberg's circumstances into account. Unfortunately, Walker builds very little of a case and almost never goes beyond the retelling of the main events. Besides, most newspaper critics have little more influence than a blogger like me (I have practically zilch, thank goodness). Many of his disappointments I can easily attribute to the kind of "hard" music he writes. He's in he same boat as a lot of other contemporary composers. His skin color probably added another bit of weight to what he had to lift, but surely not now. I doubt that his lack of performances is presently due to the racism of music administrators, rather to their ignorance of contemporary music in general, their innate musical conservatism, and their eye on the box office. And at that, he's had more performances by high-profile orchestras and artists than most. Not everybody gets a Guggenheim. Not everybody wins a Pulitzer. It's a tough road for most composers, even relatively well-known ones. That's why what they do (including, by the way, Walker) is a matter, in many cases, of heroism.

The book is strange in many ways, in that we don't find out much directly about Walker himself away from music. For example, he has children he's rightly proud of, but he never mentions the woman or women he had them by or indeed whether he ever married. Did he adopt? Autogenesis? Nevertheless, we have relatively detailed portraits of his mother and father (no one gets a really detailed portrait), his grandmother, his sister, and even a cousin and an aunt or two. It just gets odder and odder as you read.

As I've said, the prose is bare-bones and the tone is mostly matter-of-fact. We learn of commissions, premieres, concerts (Walker is a virtuoso pianist as well), and here and there (mostly in the final chapters) a bit about how one composer goes about his business. There are several appendices: a list of compositions, excerpts from reviews, and most valuable to me, a list of CDs of Walker's music. When the chance of live performance hovers somewhere around breaking the house in Vegas, CDs become the main vehicle of dissemination. There's a serviceable index, but this is not the kind of book that needs a great one.

Copyright © 2010 by Steve Schwartz.