The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

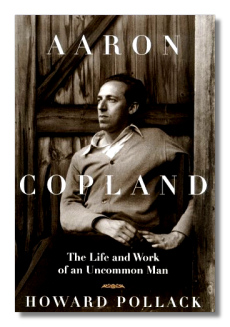

Book Review

Book Review

This joins other fine recent, substantial and well-balanced biographies of 20th Century composers: Barbara Heyman's of Barber, Tommasini's of Thomson, Burton's of Bernstein, and Carpenter's of Britten. (I am still waiting for someone to publish a good biography of Schuman.) Pollack's study of Copland's life and music is outstanding among these, in fact exemplary as a composer's biography, because he gives the music equal billing with the life. Unusually, the compositions are discussed in strict chronological order, whereas the person is presented thematically.

Pollack's previously published writing includes Harvard Composers: Walter Piston And His Students, From Elliott Carter To Frederic Rzewski (which has a full chapter on Shapero's Symphony for Classical Orchestra, by the way) and Skyscraper Lullaby: The Life And Music Of John Alden Carpenter. He is a music professor at the University of Houston. As in the first just-mentioned book (I have not seen the other) Pollack writes about music clearly and intelligibly without musical examples, in a way that non-musician readers of moderate musical literacy can understand. Someone once wrote that it was a waste of time writing about what goes on in a piece of music, because the musical listeners would be able to hear it for themselves and, for everyone else, whatever was said would not make a difference anyway. That was rubbish, of course, and insufferable rubbish at that.

To be sure, Copland's music has been much condescended to, in some quarters. I recall that, years ago on a news list, someone snorted after another person mentioned the Rite of Spring and Appalachian Spring in the same phrase. Copland referred to "sourpuss critics" of his piano sonata. (354) Pollack shows, though, that even Boulez showed respect for Copland's music – some of it anyway. Pollack also relates how various composers (like Thomson) thought Copland overly influential in deciding what music got performed (not that Thomson didn't throw his weight around, and settle scores, as critic for the New York Herald Tribune.

In a few places, Pollack challenges what he sees as general misapprehensions, such as the notion that Copland adopted serial techniques in some late works more out of peer pressure than from conviction. Pollack attributes this to Bernstein. My contrary view, which I have expressed before, is based on a reading of Copland's memoirs, specifically a conversation with Boulez that I recall him reporting. By the way, Pollack also finds fault with Bernstein's preformance of the late works in question, Connotations and Inscape, for not presenting these works as persuasively as might be wished. Pollack also challenges the notion, endorsed by Copland himself, that his work falls, stylistically, into relatively neat chronological segments. Pollack sees both the modernist and the accessible poles of Copland's creativity in all periods.

Chapters on the compositions are interspersed among the more strictly biographical chapters; 13 out of 29 are on music, all but three in the second half of the book. The works – at least 83 out of about a hundred, by my count – are discussed one by one, and many at considerable length. Brevity of the work is no bar to serious consideration by Pollack. Fanfare for the Common Man (one of three fanfares Copland wrote) is analyzed for a page or so, in terms of theme, harmony and orchestration. The Third Symphony gets extended treatment. The least satisfactory discussion, for me, is on Appalachian Spring, as it focuses much more on Martha Graham's changing scenarios for the ballet, than on the music. Typically, Pollack writes about the origin of each work and gives a summary of positive and negative ctiticisms it occasioned, as well as perfomance and recording history, in some cases, in addition to his reading of the harmonic, rhythmic, contrapuntal and instrumental elements of the work. For those who like Copland's music, this may make Pollack's book one to own rather than just to read, aside from the biographical information it contains.

Oh yes, the biography! Well, it is a biography, but with a difference. It begins conventionally enough, with accounts of Copland's family, early education and study in Paris. After that, Pollack writes what almost might be called biographical essays on various themes, which he carries through, narratively, as long as he needs to, chronologically. This works very well, because it brings together in a full way, especially for the reader who has read the two volumes of autobiography Copland wrote with Vivian Perlis and others (which I strongly recommend), accounts of Copland's professional and personal relationships with his composer-peers, worldwide; younger composers (like the very young Christopher Rouse who liked Connotations even if his family didn't); and lovers; also his political activities in the '30's and McCarthy's investigation of these in the '50's. One thing Copland did not mention to the Senators was the "communist song" he wrote in the early '30's. Copland's work for the theatre, ballet, and especially Hollywood, is presented thoroughly. Copland advanced the art of film music considerably, and was recognized for these accomplishments at the time.

A late chapter, "Identity Issues," outlines what some have said about Copland's music in terms of his Jewishness, his homosexuality and his attempts to create and promote an American sound. Much of what was said was less than convincing, especially on the first two themes mentioned.

The end of Copland's half-century composing career seems to have come gently, as Copland's inspiration, memory and mental powers generally succumbed to the dementia which had afflicted his father before him, from about 1975 to 1990 when he died. He was able to substitute a conducting career, for a time.

Pollack's sources, including the seemingly ubiquitous Paul Moor, are documented in about 100 pages of notes. There is also a list of Copland's works, a selective bibliography, and index.

Copyright © 1999 by R. James Tobin