The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

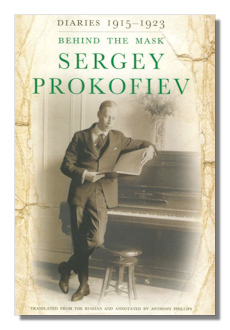

Sergey Prokofiev

Diaries 1915-1923

Behind the Mask

Translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips

Introduction by Anthony Phillips

Cornell University Press, 2008. 775 pages

ISBN-10: 080144702X

ISBN-13: B008W4CCGQ

The year 1915 began with Prokofiev and Nina Meshchersky deciding they wanted to be married. Various biographers have written that their desire was not fulfilled because of opposition from Nina's family but Prokofiev's account makes clear that this is not exactly what happened. What her family vehemently opposed was not their marriage as such but rather Prokofiev's wish to travel with Nina through dangerous wartime conditions to Italy, where Diaghilev was waiting to meet with Prokofiev concerning a ballet. Any attempted elopement was not going to be allowed to succeed. Instead of waiting for more propitious times, Prokofiev abruptly broke with Nina in a letter and they returned the ring and bracelet they had exchanged. And then Prokofiev did not leave St. Petersburg after all, because even the northern route – west, by water, instead of south, overland – was too dangerous on account of German naval warfare. He never met with Nina again, and even when he came across her later in Paris and elsewhere he did not greet her or acknowledge her with a bow. He said he was not entirely sure it was she, even on the occasion she looked at him directly. He did think of her occasionally.

In 1923, at the end of this volume, Prokofiev married Lina Codina, a singer whom he met in America and lived with in France, idyllically for a time. That she had become pregnant with their first son was revealed only in a footnote, because the diary entries for both 1922 and 1923 were uncharacteristically sparse. Although he loved her, he had been less than enthusiastic about the very idea of marriage, writing at one point that being married might be like having a stone attached to a leg.

Between these two relationships Prokofiev continued to attract and be attracted by a number of women including Stella Adler, who was to become one of the great teachers of acting. He might conceivably have married her, which would have made for a very interesting pairing indeed.

In his musical affairs during this period Prokofiev completed, in addition to piano music, his Third Piano Concerto and First Violin Concerto, his Classical Symphony, the Scythian Suite, the ballet Chout, and the operas The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Fiery Angel. He became famous worldwide as a composer and pianist but was not so successful as to prosper financially. He became acquainted with Rachmaninoff, Arthur Rubenstein, Koussevitsky and other important musicians, as well as wealthy patrons, but solo recitals tended to be financial losses because of expenses. Getting his operas produced was a terrible struggle, even after assurances had been given. The financial collapse of the Covent Garden on account of huge financial losses by Thomas Beacham, who had been a financial mainstay of it, was one thing. The taste of the managers of opera houses like the Metropolitan Opera, and the fact that Diaghilev disliked opera in general did not help. Near the end of this period, however, The Love for Three Oranges opened in Chicago the same week Prokofiev played the piano in the first performance of the Third Piano Concerto and conducted a performance of the Classical Symphony at the same concert.

The Classical Symphony is generally considered a satirical parody, but there is no evidence in his diaries that Prokofiev considered it such, or that anyone he knew spoke of it like that. In fact he called himself a classicist more than once. He did intend buffoonery in Chout and The Love for Three Oranges.

The background for all this was the First World War, the two Russian Revolutions of 1917 and the civil war between the Red and White armies. Prokofiev was apolitical, thinking of himself as a creative artist, and he was exempted from military service on account of being the only son of a widow and, as a matter of fact, as a composer. Battles in the streets were more of an inconvenience to him than anything, but he was an eye witness to some and wrote about what he saw. He put his important papers, including scores and diaries into safekeeping, and got the last train to Vladivostok, and from there went to Japan. Short of money, he planned to go only as far as Honolulu on the next leg of his journey but was able to continue by means of loans from kind people he met on the way. In California he was offered a teaching post for the coming season but it is not clear from the diary – because of missing entries – whether he actually returned for that. He went on to Chicago and New York, toured other cities in the U.S. and Canada, and sailed to France and England, thus completing his circumnavigation of the world. Both visas and ship reservations were extremely hard to come by. The fact of his being a Russian national following the Bolshevik Revolution was a factor in the visa difficulties.

On the dust jacket of the third and last volume of these diaries, Alexander Waugh, quoted from Literary Review, confesses himself "passionately engaged" with this book and predicts that "in time [these writings] will come to be ranked among the great classic diaries of European literature." I don't believe he will ever need to live that statement down.

Copyright © 2013, R. James Tobin