The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

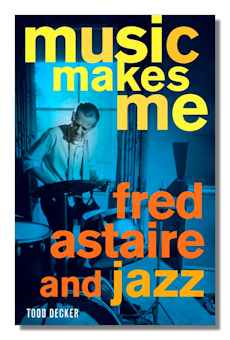

Music Makes Me

Fred Astaire and Jazz

Todd Decker

University of California Press. 2011.

391 pp.

ISBN-10: 0520268881

ISBN-13: 978-0520268883

Summary for the Busy Executive: Swellegant.

Of all the ink writers have spilled trying to capture the essence of Fred Astaire, surprisingly little of it has gone into analyzing his art – or arts, since he mastered more than one. We think of Astaire as a dancer, of course, or, as he would have put it, a "hoofer" – a designation that showed both modesty as well as an inclination to not let anybody get too close. After all, he belonged to a generation and milieu that produced art largely on instinct rather than analysis and that either dismissed analysis or were frightened by it. Today, of course, the highest praise you can give somebody in show business is "genius" – an accolade all too easily bestowed. For Astaire's generation, the gold-standard compliment was "professional," removing the creator from the long-haired preciousness and into the rough-and-tumble of the marketplace. Geniuses, of course, arose under these circumstances, and their quality yields little, if anything, to their Hochkultur counterparts. If Baryshnikov can idolize Astaire the dancer, so can I. I would also claim that Astaire sang the American Songbook better than all but very, very few. I prefer him to Crosby, for many musical reasons. However, no one, as far as I know, has yet written about him as a singer.

Even those who have talked about Astaire the star haven't emphasized what he did as a dancer. The best of these, The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Dance Book by Arlene Croce, talks about their numbers in terms of story, production history, and the ethos and conventions of Thirties Romance. Decker breaks new ground in actually breaking down the dances themselves – how they fit the music and vice versa, since Astaire sometimes radically changed the music he was given. He emphasizes Astaire the maker of musical "numbers" and talks a good bit about the performer's rhythmic habits. He also relates Astaire to the other tappers of the period, almost all of them Black. His dance style was almost always tap or ballroom fantasy, unlike Gene Kelly, more influenced by ballet and modern dance. Astaire eschewed the elegance of Bill Robinson and Honi Coles, both of whom emphasized the front of the foot, for the earthier style of John Bubbles, who came down hard on the heel. We think of Astaire as elegant, mainly because most of us register him from the waist up. Even his elegance, however, is, in Baryshnikov's phrase, "dangerous," especially as it relates to balance. Astaire banged himself up plenty in the course of his career, all to make us believe that, due to his light heart, he nonchalantly defied gravity.

Decker makes quite clear Astaire as the auteur of his numbers. He almost always conceived them, although not alone, figured out the music he needed, worked with (usually) his rehearsal pianist – who generally was also an arranger in fact, if not in credit – and planned the camera moves, as well as rehearsed. His box-office clout and his reputation for completing his jobs on time and either on or under budget ensured that the studios left him alone. He may not have been the "onlie begetter," but he had the expertise to strongly direct each number in specific ways. Of course he could dance. He also played decent stride piano, a style that requires you to be very, very good before you can play it at all, as well as drums. You can see some of this in his numbers on screen. That's all Fred, not a dub. For fun, he used to play his drum kit at home to the recordings of the best swing bands. At any rate, he himself could tell an arranger what he required, if by no other means than playing it.

Decker takes a pioneering structural approach to the numbers, answering the question how Astaire put them together. He considers them pretty much in isolation from the rest of the film. Since the old Hollywood studios ran on the factory system, there's a boatload of primary paper one can sift through, including production sheets, which include credits as well as timings of music and dance. Beyond that, we get Decker's musical analysis – which, incidentally, relies not on musical type, although there is some, but on the reader's ear. Many of the numbers Decker talks about you can watch on YouTube, and I would guess for most of us, who have either never seen the number in question or can't recall it in detail, these videos help a lot. I had a great time watching and reading. Even Astaire's obscure sequences from forgettable movies astonish me.

The really interesting part of Decker's book relates to jazz, a word whose definition changed by the decade. Astaire stayed relevant to popular music from the Twenties through the Sixties (the decade of his TV specials). Astaire's career began in the Jazz Age, where jazz could mean anything from Paul Whiteman to Louis Armstrong and J.P. Johnson. Gershwin, Berlin, and even Kern were considered to have written jazz. In other words, jazz was just about anything based on black syncopated music. The Thirties brought greater harmonic and rhythmic sophistication – the Swing Era, which actually lingered through the early part of the Fifties. The Rock revolution initially stymied Astaire, but he figured out an accommodation, if not a surrender, to it.

Early on, Fred (from Nebraska) felt the pull of black music. Along with Gershwin and others, he regularly went to Harlem during the Twenties to hear bands and players. He also attended Black musicals and revues on Broadway. I never thought of Astaire as politically liberal (because he wasn't), but he brought black performers and arrangers into his projects on a fairly regular basis at a time when the studios and movie unions rigorously patrolled the color line. He had the juice to get what he wanted. For one thing, hard, driving, blues-based swing appealed to his magnificent sense of rhythm. For another, he genuinely admired black musicians. As racial attitudes opened up, he pushed envelopes even further, in his casual way. The screen image of Blacks is background and apart in a number like "Slap That Bass." Astaire assumes the role of fascinated tourist who wanders in on a ship's engine crew (by the way, the sparklingest in not only the movies, but in the history of mankind) and then takes over the music. By his TV specials of the Fifties, Blacks are equal stars in their own right, who sometimes allow Astaire to join in. Consider that even in the Sixties TV created white reaction over nothing at all (Petula Clark giving Harry Belafonte a congratulatory peck on the cheek or Bill Cosby playing an educated Black on I Spy, for example), and you see something of the power of Jim Crow. Astaire's absorption of jazz shows up of course in his tap rhythms – in the very structure of his dances, where a 32-bar pop song can often be abandoned for a series of 16-bar blues choruses during the tune's "expansion." Sometimes he jettisons the tune altogether after its first statement, replacing it, again, with blues choruses which play to the number's end.

The book comes with great endnotes and a serviceable index. Decker puts penetrating thought and solid research into very readable prose. I loved particularly his discussion of "broken rhythm" and "dancing on the stems." This book is a milestone in Astaire studies.

Copyright © 2013 by Steve Schwartz.