The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

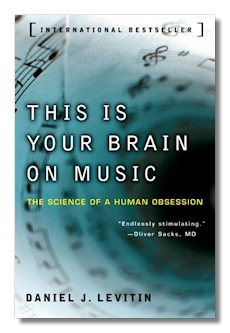

This Is Your Brain On Music

The Science Of A Human Obsession

Daniel J. Levitin

Penguin Group

2006, 2007. 322 pages; previously published by Dutton

ISBN: 0452288525

Some interesting things I learned from this book:

That music activates more parts of the brain than any other mental activity. That hearing a piece of music activates the same parts of a listener's brain as it does in the brain of a musician playing the piece. That ordinary untrained people can reproduce the exact pitch and tempo of songs they are familiar with a single version of. That timbre is the musical element most easily remembered and which, when heard, can most quickly (fraction of a second) enable a listener to recognize a piece of music. That the octave is central to all musics, based as it is on laws of physics. That the average female voice is exactly an octave higher than the average male voice. That divisions of the octave – and its beginning pitch – are a matter of arbitrary convention, but that irregular divisions of the octave in some scales make music easier to remember.

Levitin is an internationally distinguished neuroscientist with chairs at McGill University. Prior to his academic career he worked as a record producer, sound engineer and session musician. He studied music at Berklee in Boston. His personal musical interests are mostly with popular music but in this book can be found a brief discussion about Mahler's Fifth Symphony in relation to his Fourth and other references to classical music, I think that his scientific results will apply to all kinds of music.

What I found particularly refreshing about Levitin's extremely well written book is that he simply presents, as scientific fact, claims that are often tediously argued as some kind of irresolvable philosophical problem. I also particularly liked his emphasis on timbre and rhythm, elements that get short shrift in many musical discussions. On rhythm, incidentally, toward the end of the book he introduces a "complexity curve" which makes some sense of the fact that individuals have a very varied capacity for enjoying, say, complex Latin rhythms.

Some open questions that Levitin takes up have to do with the nature of musical memory. Does it fill in the blanks, so to speak, or is it a more exact recall capacity for details of music; he finds both extremes unsatisfactory. He also argues, in the last chapter, that music first came about in the evolutionary process as part of the courtship process.

The book begins with a clear and substantial account of the rudiments of music, which he invites musician-readers to skip; but I recommend that musicians at least skim through this because it gives meaningful context to the concerns of his later chapters.

Copyright © 2007 by R. James Tobin