The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

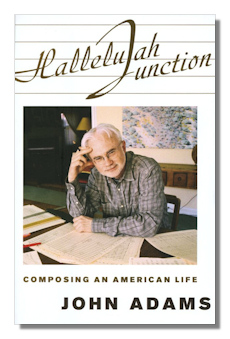

Hallelujah Junction

Composing an American Life

John Adams

New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2008. 340 pages

ISBN-10: 0374281157

ISBN-13: 978-0374281151

Summary for the Busy Executive: Hallelujah.

In addition to his standing as one of our current best composers, John Adams happens to be a prose master. Most of us, including me, plod our way through a sentence just trying to say what we mean. With Adams, the prose seems effortless and full of sharp poetry besides – not the poetry of the High School Sensitive, at any rate, but the energetic, compressed expression and keen observation that comes of the union of genuine thought, experience, a great eye, and a feeling for the music of the American language. I always look forward to Adams's notes on recordings of his own music because they give me a glimpse into his mind as he composed the work. You get more of the same here.

Primarily, Adams looks back on his life and mainly his work, so this isn't a straight autobiography. For Adams, his work comprises a good deal of his life and his conscious thought, and you don't get exhaustive detail on the standard events. That will undoubtedly come from some academic years from now, after Adams's death. Basically, this book gives us the mind of the composer as he creates something out of nothing.

The book's subtitle makes an interesting point. Adams thinks of himself and his work as particularly American in a time when such nationalism is very much not in vogue, nor was it when Adams was a student. American composers saw themselves very much a part of an international community. The enterprise of the Copland generation seemed quaint to the young bloods. The widespread adaptation of European avant-garde styles and techniques undoubtedly contributed to this. I think Adams actually had a wider view than the internationalists. As a young composer he wanted to express himself as an individual and worked to discover what he had to say and how to say it, rather than to write a "classic" piece, in the mainly Germanic tradition. In asking what shaped his musical self, he came up with not only that tradition, but with jazz, rock (particularly Jimi Hendrix), and the American Songbook, among other things.

Adams and I came of musical age at roughly the same time, the Sixties (he's a year younger). Many of his concerns as a composer were mine as a listener. Although we liked and admired at least some of the avant-garde, much of it didn't seem particularly relevant to our lives. It seemed too confined and restricted in the experience it embraced. Keep in mind that during the Sixties, we had a huge range of ideas and social currents competing for attention – a musical, cultural, and philosophical smorgasbord. To paraphrase Steve Reich, it was hard to feel Viennese fin de siècle Angst in Ohio, in the parking lot of a Burger King. Dodecaphony in particular seemed at odds with American optimism in the postwar era. Viet Nam would soon take its toll on much of that, but even so optimism remains a major part of the American outlook. So as young composition students churned out their versions of their teachers' work, Adams began his quest to go beyond the accepted styles. A move from New England to the somewhat isolated (and exotic) California of the time helped free him from East Coast biases. Tape and electronic music engaged him for a while, as did an energizing encounter with what became known as Minimalism through Terry Riley's seminal In C. As Adams lived through the Sixties and Seventies, much of what he encountered stuck to his artistic self, and through a combination of alchemy, luck, and a lot of hard work, he emerged with that most valuable composer's asset, a personal voice. You may not care for Adams, but for Adamic music, you pretty much have to go to him.

Adams takes you through his intellectual struggle to arrive at his mature self, and in doing so, gives his opinions of several key figures. These are both balanced and frank, and the latter quality has upset certain readers. But a composer (or any artist, really) makes no claim to critical objectivity. He is honestly ruthless in deciding what he can and can't use. He also tries to reconstruct how he got from a blank sheet of paper to a finished work and discusses several of his major pieces, like Harmonium, On the Transmigration of Souls, Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, Chamber Symphony, violin concerto, and so on.

Writing about yourself's a tricky business. How do you manage not to come off like a self-absorbed, pompous jerk? Adams creates a persona modest, funny, intellectually incisive, and quick to intelligently admire others. I can't say whether the creation is a natural expression of himself or a conscious literary creation. One feature of Adams's prose is that you don't see him sweat. Many have ranked this book with the best composer memoires – particularly to that of Berlioz. I actually found more parallels to the writings of Ralph Vaughan Williams – the same search for self, the same energy in clearing away the intellectual brush, the same modesty. Who knows? I can say that Adams at least has given us an important look at a particular place and time. I suspect that it will long remain an important source for scholars and critics to come.

Copyright © 2013 by Steve Schwartz.