The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

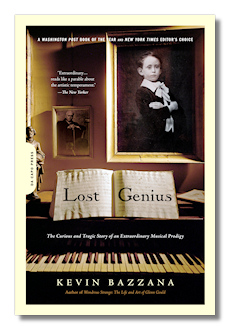

Lost Genius

The Curious and Tragic Story

of an Extraordinary Musical Prodigy

Kevin Bazzana

Da Capo Press, 1907. 383 pages

ISBN-10: 0306817489

ISBN-13: 978-0306817489

Ervin Nyiregyhazi (1903-1987 – his name is pronounced nyeer-edge-hah-zee) was a Hungarian American pianist devoted to the music and aesthetics of Franz Liszt in the most extreme sense. For him emotional expression was the supreme goal in performance, without regard to any performance tradition and even without high regard to adherence to a score. His performances tended to be very slow and extremely loud, though he could exhibit a wide dynamic range, but with some extraordinary tonal effects, some produced by the way he used the pedals and some by the way he pressed, rather than struck the keys. Sometimes his forceful playing left blood on the keys, though, and early in his career a representative of the Steinway Company made sure that he would not be entrusted with a Steinway piano. (Late in life he re-encountered a piano in Hungary with a key still broken from his playing decades before.) Knabe paid him every time he used one of their pianos, though. He impressed many listeners enormously; others despised his playing. The critic Harold Schonberg may have been on both sides of this divide. Nyiregyhazi was also a composer of over a thousand works, many quite gloomy in mood, especially toward the end of his life. He considered his compositions great but few have agreed with him. Nyiregyhazi's memory was prodigious. At quite a young age he read a new published work at the counter of a music shop and that evening played it from memory as an encore. In later life he was able to perform works from memory without having refreshed that memory in decades – not always with complete fidelity to be sure. At an early age he was the subject of an academic study of prodigies

By many standards his personal life was a disaster. He was exploited as a child prodigy by his mother – his father having died when he was quite young – and she kept him in an infantile state. Well into adulthood he was actually unable to tie his own shoes or cut his own food. He was forced to perform in short pants until he rebelled at age 16, telling his mother that if she still insisted on that he would cancel an important concert and, what is more, if he were not allowed to live on his own he would renounce his performing career.

He got his way but did not do well in his career, both because he was not well represented and because he was not particularly skilled in human relations, and that is an understatement. He had high self-regard as a musician but was greatly lacking in self confidence in other ways. Bazzana even calls him paranoid. Most of his life he was quite poor, even destitute, though mostly he did not seem to mind. He was attractive to women, however, and no fewer than ten women married him; some were devoted to him and to some he was devoted. It would not be inaccurate to say that he became addicted to sex of all sorts, had many affairs, frequented prostitutes and massage parlors etc. Bazzana will tell you more about this than you may wish to know. He also drank prodigiously, partly in order to function socially or musically.

Nyiregyhazi knew many famous people, from Eugene Ormandy who tormented him at the conservatory to various Hollywood celebrities. Schoenberg was impressed with his playing and recommended him to Otto Klemperer – who was not similarly impressed. He had, however, played under Nikisch with the Berlin Philharmonic when he was six. After decades of hardly playing at all, in the late 1970's Nyiregyhazi's fortunes seemed to be made at last when, thanks to Richard Kapp the Ford Foundation decided to invest in the preservation of his performances and some recordings were made by Columbia Masterworks, some of which did rather well for classical recordings. Some are currently available. He also interested some Japanese musicians involved with the establishment of a new school of music; they liked Nyiregyhazi's musical aesthetics and brought him to Japan. His last wife gave these sponsors greatly detailed advice concerning his enormous need to have respect paid to him, lest he refuse to cooperate even with well-wishers.

Every word of Bazzana's title and subtitle is well chosen. Ervin Nyiregyhazi was a real piece of work. But Bazzana, the Canadian musicologist who previously authored a book about Glenn Gould, takes his subject very seriously and has produced a biography that is both scholarly and extremely readable. He has no thesis to propound about prodigies and is not one of those biographers whose main aim is to reveal the clay feet of creative geniuses – though he certainly is not out to conceal those feet either. I have the sense that Bazzana admires the artist and is sympathetic to the person Nyiregyhazi was in spite of his enormous limitations as a human being.

Copyright © 2008, R. James Tobin