The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

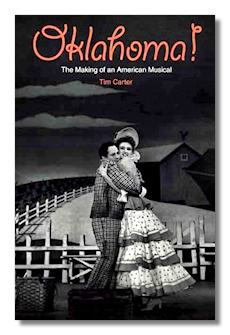

Oklahoma! - The Making of an American Musical

Tim Carter

New Haven & London: Yale University Press (2007) 327pp

ISBN: 030010619X

ISBN-13: 978-0300106190

Summary for the Busy Executive: Okay.

The bloom on the rose of the musical Oklahoma! has faded a bit since its Forties premiere. It ran – unusual for the time – four years to generally boffo business, won a special Pulitzer Prize, and provoked a rash of "think" pieces not only from theater critics, but from classical-music counterparts. Even the high-theater critic and theorist Eric Bentley singled it out, though not favorably. In its wake, it gave rise to all sorts of revisionist history about the American musical theater: that it was the first "play with music," that it was the first integrated musical show, that it was the first to incorporate ballet, and so on. All of these propositions are easily disproved.

Indeed, Oklahoma! pushed the innovation of the musical far less strongly than Kern's Princess shows, Berlin's Music Box shows, Show Boat, Of Thee I Sing, The Cradle Will Rock, Johnny Johnson, As Thousands Cheer, Lady in the Dark, Pal Joey, and Knickerbocker Holiday, to name just some of its distinguished predecessors. As far as its music goes, with the exception of "Out of My Dreams" and "Lonely Room" (a song very few people have heard of, let alone heard), it really doesn't come up to the best of Rodgers and Hart or, for that matter, of Rodgers and Hammerstein themselves. Alec Wilder, in his cranky classic on the American popular song, has no kind words for it whatsoever. Nevertheless, the show has achieved the status of an icon.

It almost never happened at all. From the beginning, the production suffered a plague of money shortages. It threatened to sink its producers, the Theater Guild (who had also presented Gershwin's masterful Porgy and Bess). The accounting leant toward the "creative." If Oklahoma! hadn't been a hit, some very prominent people might have wound up in jail.

Tim Carter untangles fact from myth, account from conflicting account. The creative team tended to emphasize their acumen and prescience – particularly director Rouben Mamoulian and choreographer Agnes De Mille – with the show's mounting success. The book's strength is Carter's research. If you want to know production costs or weekly expenses, you can find much of it here. Carter does less well on aesthetic analysis, and one looks in vain for a controlling thesis for the book. Furthermore, Carter writes in a style one could charitably describe as "academic," although many in the academy write better than this. He is particularly drawn to the word "diegetic," and at times he doesn't seem to know what the word means ("relating to narrative"), as in:

Similarly, in musicals (and for that matter, in opera) music always draws attention to itself as music even when it pretends to be emotional articulation; thus it will be diegetic to the genre even if it is not diegetic within the drama in terms of verisimilitude.

Surely at least one of those diegetics is wrong. You may catch yourself nodding off in the middle of a paragraph. Nevertheless, Carter comes up with interesting tidbits. My favorite concerns the near-decade it took for Oklahoma to adopt the eponymous song as its official state anthem. At least one Western Solon objected to the line "Every night my honey lamb and I" as "indecorous."

As usual with the current crop of books from academic presses, annoying little errors pepper the text. The soprano is Eleanor Steber, not Sterber, and Harold, not Howard, Arlen wrote Bloomer Girl. And this is Yale, for heaven's sake.

Copyright © 2007 by Steve Schwartz.