The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

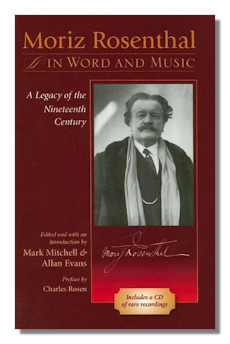

Moriz Rosenthal in Word and Music

A Legacy of the Nineteenth Century

Mark Mitchell & Allan Evans. Preface by Charles Rosen.

Indiana University Press. 2006. 185 pp.

ISBN-10: 0253346606

ISBN-13: 978-0253346605

Summary for the Busy Executive: The little giant.

Moriz (or Moritz) Rosenthal, a major pianist of his time, most people today probably would recognize only as a name, if they recognize him at all, mainly because he didn't record all that much and even then not often the repertoire on which he built his reputation. I would say that he has survived mainly through his wit – often bitingly satiric and very Viennese. For example, he remarked after a heavily hyped concert by Paderewski, "He's good, but he's no Paderewski."

Many people who know what they're talking about (not me) consider Rosenthal the finest pupil of Franz Liszt. As a prodigy, he also studied with Karol Mikuli, a pupil of Frédéric Chopin. Born in Polish Galicia, his Jewish family moved to Vienna so 13-year-old Moriz could study with Rafael Joseffy, a pupil of both Carl Tausig and Liszt. As an adult, he too became a Liszt pupil. His own pupils included Charles Rosen and Robert Goldsand, and Brahms and Johann Strauss II (the pianist dubbed him "the second and only") considered him a friend.

Rosenthal had both formidable technique and formidable intellect. For example, one of his parlor tricks was to play Chopin's "Minute" Waltz in thirds faster than most pianists could play the original. As a rather short boy, he took Napoleon for his hero and then, learning of Bonaparte's later career, dropped him for Beethoven. Rosenthal never grew tall, and I think it significant that he chose another shortie as the object of his adulation. In addition to his piano studies, Rosenthal acquired culture, apparently mainly on his own. He read the ancient Greeks in the original, among other things. He also emerged as a superb writer.

Liszt instilled in him the aesthetic value of raising the composer above the performer. The performer had to discover the secrets of the score, considered sacred text, in such a way that revealed the mind of the composer. Of course, standards of artistic fidelity change with the times, but Rosenthal stands among the least dated pianists of his era. How did one happen upon the intent of a composer, particularly a dead one you couldn't ask? Rosenthal assiduously read the letters if they existed or biographers and gave special weight to those writers who knew the composers, who "saw Shelley plain."

Charles Rosen provides a charming mini-memoire of his lessons with Rosenthal and his wife. According to the contract his father signed, Rosen should have had one lesson a week with Mrs. Rosenthal, by all accounts a great teacher, and one a month from the eminence. In practice, at the end of a lesson, Mrs. Rosenthal usually said, "Now go in and amuse the old man." I suspect that Rosenthal had a sense of obligation. His family had to scramble to come up with the money to pay for his pianistic education. This may have been his way of giving back to those with talent, but I don't know this for certain and often think in Romantic clichés.

The volume consists of: the extant parts of Rosenthal's autobiography; a selection of articles; several reviews of Rosenthal's concerts and Rosenthal's often scathing replies to his unfriendly critics; a section of Rosenthal's aphorisms; appendices on his humor, his concert repertoire, and his recordings; a CD of some of the pianist's recordings, with a few premieres. The notes are mostly informative and the index both fine and welcome. I don't agree with the editorial policy, but I admit Mitchell and Evans carry it out excellently. At issue is the question of repetition. Rosenthal sometimes recycled material for different articles. Rather than repeat these passages, the editors decided to use what they considered the best version. To their credit, they mark the passage so that you recognize an editorial insertion. They want to favor the "general reader," who apparently has no interest in such a level of detail, rather than the scholar. I'm no scholar, but I believe this gives a false impression of Rosenthal the writer. It's like splicing "best takes" rather than recording an entire performance as it happened. This story from Paul Hume: A pianist known for his Mozart and Beethoven decided to tackle the Brahms d-minor concerto, a finger-buster. He kept messing up, so the session proceeded in dribs and drabs, with the engineers joining the pieces. When they had a movement, the engineers, pianist, conductor, and producer would listen. At one point, the pianist said to the conductor, "Not bad, huh?" and got the reply, "My boy, if only you could play like that!" I suppose I'm just geeky enough not to mind repetition.

The accompanying CD confirms the plaudits, at least as far as Rosenthal's virtuosity and sense of structure go. One hears stuff you'd swear needs at least another five fingers (his paraphrase of the Blue Danube Waltz, for example). Chopin is the composer most represented (no Beethoven at all, because Rosenthal didn't record any). The pianist approaches Chopin almost Classically – no swoops or swoons. Rosenthal rated Chopin just slightly lower than Beethoven. However, the sound, God help me, is aggressively "historic." The static, wow, and flutter overwhelm not only the subtler aspects of his playing, but sometimes actual notes. He occasionally seems too fast for the microphone. There are no acoustic recordings because he began to record only in the late Twenties. One can also get Rosenthal's complete known recordings on APR, but I haven't heard any of the five-disc set. I wish Pristine Classics could get hold of Rosenthal's tracks and clean them up.

Copyright © 2014 by Steve Schwartz.