The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

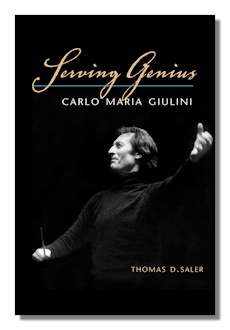

Serving Genius

Carlo Maria Giulini

Thomas D. Saler

University of Illinois Press, 2010. 256 pages

Cloth; acid-free paper

21 black & white photographs

ISBN-10: 025203502X

ISBN-13: 978-0-252-03502-9

Carlo Maria Giulini was the antithesis of the authoritarian conductor. Unlike Toscanini, Szell and Reiner, for instance, he never raised his voice or ruled by fear. Invariably courteous and considerate of feelings, he gave respect to his players and stressed mutual effort in orchestral music-making. He had no enemies. Having been an orchestra player himself – viola – he tended to be egalitarian, going out of his way to give even a newly hired second violinist a welcoming greeting. He did get his way as a conductor, but by persuasion, inspiration, manifest commitment to the music, superlative standards of performance, and by ways mysterious even to him. In rehearsal, for which he demanded and got more time than most conductors, especially today, he emphasized phrasing and melody, in meticulous detail. He also focused on balance, even asking a second clarinet to hold back and the third clarinet to play with more volume; and he worked on string tone, which became full and rich under his direction. Even years after he had left an orchestra and the sound of the strings had changed under other conductors, string players found themselves playing works they had often played for Giulini with that same full tone.

On the podium, Giulini shaped phrases with his enormously expressive left hand, which I could not help noticing during the one concert of his I was fortunate enough to attend. With his baton, he was said to conduct "through" the music, rather than to beat the time rigidly. Melody mattered more than rhythm to him, not that he neglected the latter. He also conducted with his facial expressions and his eyes, even telling the players of an orchestra new to him that he did not know their names yet but he would soon know their eyes. A rebuke or taking note of a mistake did not require vocal expression from him. When young he was extremely energetic on the podium but he once said he did not know what he did on the podium and once when he saw himself on a video he became so self-conscious that his performance later that day was spoiled.

Giulini's repertoire was limited to works he loved, which, aside from those of Britten, included few composed after the middle of the last century, which he left to others, even when he was music director in Los Angeles. He had a particular affinity for Brahms. His early performances of Beethoven did not satisfy him and it was many years before he undertook the Eroica and Fifth Symphonies again. When he did, the results were superb, as in the slow but intense Eroica I heard that wonderful evening in Chicago, not long before he left for Los Angeles, where he produced a fine recording of it. His Deutsche Grammophon recording of Dvořák's 8th Symphony was so satisfying that a Fanfare reviewer declared that no further recordings would be needed. The legato phrases in that reading are positively caressing.

Such detail is the stuff of this fine biography, particularly in the chapter on his Chicago years and the one following, called "Molto, molto espressivo." It is a full account of his life, as well as his work, though, from his early years to his last, which included an account of hiding in an underground tunnel during the German occupation of Italy toward the end of WWII, to avoid internment; an account of how he was persuaded to become Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the negotiations which spared him the usual administrative chores so that he could focus exclusively on making music; and his many engagements all over Europe, Britain and the United States, as well as his many recordings, sometimes of the same works.

The biography is a labor of love on the part of the author, who lists over fifty interviews of persons associated with Giulini, from 2005 to 2008. Giulini died in 2005 and this book was published five years later. Saler is a conservatory-trained musician who sang for many years in the Milwaukee Symphony Chorus, which would have put him into close proximity to the Chicago Symphony (eighty five miles down the road), which in Giulini's years there used to play in Milwaukee as well as Chicago. Saler begins his preface by saying that "As a young conducting student in 1973, I had the privilege of sitting a few feet from Carlo Maria Giulini as he conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in Mahler's First Symphony. To this day, it remains the single best performance of any work I have ever heard." Several of the players that Saler interviewed expressed the most fervent admiration for this conductor also, both as a musician and as a person. Not all players agreed with his interpretive choices, of course, but, aside from one concertmaster early in his career, this does not appear to have resulted in personal conflict. Now as for singers – some of them Giulini declined to work with again.

The book is highly readable and musically substantive. Strongly recommended.

Copyright © 2011, R. James Tobin