The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

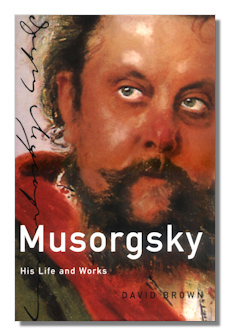

Musorgsky

His Life and Works

David Brown

New York: Oxford University Press. 2002.

ISBN-10: 0198165870

ISBN-13: 9780198165873

Summary for the Busy Executive: Cluttered.

David Brown has specialized in 19th-century Russian music, producing among other things the standard biography, in four volumes, of Tchaikovsky and a pretty good one-volume introductory cut-down. Here, he takes on the Tchaikovsky's equal, though opposite, Mussorgsky – or, as Brown spells it according to the latest academic fashion, Musorgsky. Mussorgsky died young, his output comparatively meager. Practically every work he wrote falls into the category of either juvenilia or early. But his assurance, his breathtaking originality almost from the get-go, the powerful mixture of genius and immaturity, and his inability to repeat himself artistically guarantees his place as one of the great composers of the Nineteenth Century and a progenitor of Modernism.

I wish I could call Brown's book a success. Brown has done what I thought impossible: he has managed to make Mussorgsky boring. Of his Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music I complained about the lack of technical information as well as about the lack of any substantive discussion of the originality of Tchaikovsky's achievement. Here, Brown gives us plenty of technical detail, but his argument gets lost. In short, we get pounded with detail for apparently no reason. Yes, the Pretender's love music in Boris Godunov lies in the key of E, but so what? Why does this matter? What does the key tell us about the drama or about Mussorgsky's structural planning?

In his introduction, Brown mentions Richard Taruskin's Musorgsky: Eight Essays and an Epilogue, which I reviewed recently, and notes that he has disagreements. Apparently these arguments mean more to specialists than they do to me, since I really didn't find all much out of synch with my memory of the Taruskin. However, Taruskin argues better and more pointedly than Brown. I learned a lot about Russian music in general and Mussorgsky in particular from Taruskin's book, even though the essays covered smaller ground. Brown's prose wanders all over the place. He mentions and even cites in musical type differences between the first and second versions of Boris Godunov, but, beyond the usual (lack of female roles and so on), leaves open the question as to why the composer revised. It tired me so that I could read no more than five pages at a stretch. Part of this, I'm convinced, arises from the lack of an argumentative spine running through the book. Brown bogs us down, again, for no reason.

I happen to know Mussorgsky's music in great detail. Boris is one of my three favorite operas, and I can hum long sections of it at a stretch. I once spent a year learning Pictures at an Exhibition on piano (I still couldn't play it), and I've sung the Songs and Dances of Death. Brown often cites score numbers without putting in a musical citation. I have no idea what this means to people with no scores or no recording. On the other hand, Brown doesn't address scholars or specialists, either, who presumably already know all this stuff.

Of all Mussorgsky's music, Brown does best on the songs, especially the Sunless and Songs and Dances of Death cycles. Perhaps his heart lies closest to these. The operas and Pictures fare less well.

Brown never really gets beyond chronology in his discussions of either Mussorgsky's life or his work. When I read, I don't want just facts. I want an argument, a thesis based on the facts. I wish I could have found one. The one insight I gleaned was the centrality of Mussorgsky's songs to the bulk of his work, and I had to work hard for it myself, connecting one set of Brown's facts to another. I wish the book had been better at this. Furthermore, accounts of Mussorgsky's life are handicapped by the fact that we don't know all that much about it. Months go by without any documentation of what the composer may have been up to, and this state of affairs worsens the closer we get to Mussorgsky's death (which, ironically, is surprisingly well documented). One assumes that the composer was busy drinking himself to death or composing. Most of what we have convinced ourselves we know of Mussorgsky's life comes down to inference. Brown neither goes beyond the facts nor provides much insight into the composer's personality. He contents himself with reciting "just the facts." Obviously, Mussorgsky had demons. Unfortunately, Brown won't satisfy your curiosity beyond noting the composer's severe alcoholism.

In short, the book is hardly worth the trouble.

Copyright © 2009 by Steve Schwartz.