The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

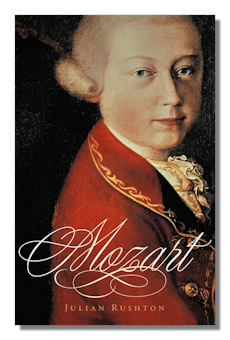

Mozart

Julian Rushton

Oxford (The Master Musicians series). 306 pages

Hardcover 2006

ISBN-10: 0195182642

ISBN-13: 978-0195182644

Paperback September 2009

ISBN-10: 0195388259

ISBN-13: 978-0195388251

Julian Rushton has had a distinguished career. He is Emeritus West Riding professor of Music at the University of Leeds; he served as President of the Royal Musical Association from 1994 to 1999; he is Chairman of the Editorial Committee of Musica Britannica and has been editor of Cambridge Music Handbooks, to which he contributed a volume on Don Giovanni. He is the author of a book on Mozart's Idomeneo (Cambridge), as well as The Musical Language of Berlioz (Cambridge) and The Music of Berlioz (Oxford).

Some of Rushton's peers have high praise for this volume. Cliff Eisen says that it includes the "finest short biography of Mozart that I know." In a somewhat back-handed critical compliment, Charles Rosen says: "It is too short – not too short for Mozart but for Rushton, who has certainly more to say that would be of interest." My own reaction is that it is indeed too short, both in the biographical chapters and the discussions of music. In contrast, the recent volume in this series on Tchaikovsky, by Roland John Wiley, at nearly twice the length, is much more engaging, especially for the musically-informed general reader, with respect both to biographical and musical details. Both books deal with biography and the works in alternating chapters.

Biographically, Rushton's account is concise and well-written but comes to something around a hundred pages, with Mozart's life before Vienna given half of that. One wants more detail, especially about the production of Mozart's last operas, the circumstances of the composition of the Requiem (though Rushton does indicate which portions of it were sketched or written out by Mozart), and Mozart's death. Particularly interesting, though, is an explanation of why he, as well as J.C. Bach, was unsuccessful in Paris, having to do with reaction against Gluck: Mozart was not given an opportunity to show that he could absorb both French and Italian musical currents. As a guide to the history of Mozart's compositions, Rushton's account is adequate and can serve as a reference.

The fact that Mozart's compositional output was several times greater than Tchaikovsky's makes Rushton's compression of his musical analysis appear strained, in comparison with Wiley's book. Wiley discussed even individual songs by Tchaikovsky; Rushton discusses just about all of Mozart's greatest piano concertos in a single chapter, and does so in a manner which requires rather sophisticated knowledge of technical terms. For instance, the term "ritornello" is central to his summary of concerto form and he uses this term, undefined, five times in eight lines. He makes short shrift of the earlier symphonies, a decision in which I can heartily concur, and it was gratifying also to see that he finds particular merit in #29 in A (K. 201).

Rushton includes fifty musical examples, from about thirty-five works, quite a few of those being early ones. These run as long as 72 bars of Symphony 27 (K. 199), filling about five pages in this case.

It is difficult to decide the target audience for this work. Not a popular work, to my mind, contrary to the views of some reviewers, it might be of particular interest to advanced music students for the expert musical analysis it includes and for the musical examples they will be able to read. As there is limited direct reference to these in the text, however, the reader with more limited expertise can skip the score-reading and even the more advanced analysis and concentrate on the more general account of the development of Mozart's ability and style, and the chronological account of just when in Mozart's career he wrote certain groups of works, notably the concertos and quartets.

As with other volumes in this series, the supplementary features are very useful for reference purposes. They include a Calendar; a List of Works, by type of work, with dates, keys and Köchel numbers; 17 pages of "Personalia"; and an index with emphasis on particular works by Mozart.

Copyright © 2009, R. James Tobin.