The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

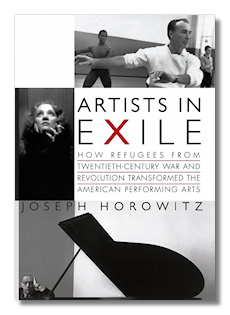

Artists in Exile

How Refugees from Twentieth-Century War and Revolution Transformed the American Performing Arts

Joseph Horowitz

New York: Harper Collins. 2008.

ISBN-10: 006074846X

ISBN-13: 9780060748463

Summary for the Busy Executive: An ambitious program, sloppily carried out.

Books on this subject have been needed for a long time. We have gotten books on individual figures, like Toscanini and Stravinsky, but not a history of the diaspora in which they took part. The interwar years saw the greatest migration of scientific and artistic talent probably in all of history, as writers, physicists, mathematicians, composers, and movie and theater people fled both the Russian Revolution and the rise of the Third Reich. Arguably, Europe and Russia have still not yet recovered, while the United States has been living off the intellectual capital created by these men and women since. George Balanchine created a new American ballet. Koussevitzky energized the best American composers by giving them a consistent and strong platform from which to present their work. John von Neumann thought up the first modern computer, whose conceptual design hasn't changed in seventy years. Kurt Weill helped extend the artistic possibilities of the Broadway musical, while Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, and Ernst Lubitsch forced the movies to grow up.

Horowitz announces his grand design early on in the book: to show how these figures changed America and how America changed them. As I say, this book needed to be written. However, so many factual errors plague it that one wonders whether anybody bothered to proof it at all. Also, there are many important figures Horowitz leaves out, and with rare exceptions, we still get little more than a couple of lines on most of those he mentions. Horowitz seems uncomfortably stuck between the archetypes he needs to make the case and a wish to be comprehensive. The still-huge cast of supporting characters tends to overpower the points he wants to make. Often, he will go through a career only to leave, at the end, the reader wondering why.

More important, however, the book often relies to a distressing degree on What Everybody Knows. As far as I can tell, there's very little original analysis. Stravinsky in particular is reduced to his Russian and early Paris works, while his American and late French music is viewed as somehow less. According to Horowitz, these weaker pieces include, by the way, his Symphony in Three Movements, Symphony in C, The Rake's Progress, Threni, and the Requiem Canticles. Robert Craft appears in the familiar role of the Svengali who led the Master astray, rather than as the man who facilitated the composer's last great harvest. Szell is the petty dictator who turned the Cleveland Orchestra into an automaton, and so on. You might be able to guess without reading the book what he says about Stokowski.

The problem with all of this is not really the viewpoint itself. After all, Horowitz is entitled to his opinion. But it doesn't often seem like he gives his own opinion. He neither argues nor fights for his opinion. Instead, he seems to continually dip into the sack of received opinion. The problem with that comes down to the fact that conventional wisdom tends to stay stuck while perspectives change due to a few brilliant minds, that art and history demand fresh encounters if they are to be anything but dead. A notable exception to this reliance on received wisdom is Horowitz's nuanced portrait of Kurt Weill. While I don't agree with Horowitz's conclusions down to the final particular, at least he's not merely recycling other sources.

Perhaps Horowitz originally wrote a much longer book which his editors eviscerated. If so, they did him no favors.

Copyright © 2008 by Steve Schwartz.