The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Albéniz Reviews

Granados Reviews

Falla Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

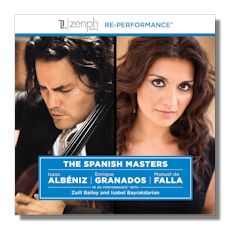

The Spanish Masters

In Re-performance

- Manuel de Falla:

- 7 Canciones Populares Españolas 1 (excerpts, arr. Maréchal)

- 7 Canciones Populares Españolas 2

- El Amor Brujo – Canción del Fuego Fatuo 2

- Soneto a Córdoba 2

- Isaac Albéniz:

- La Vega 3

- Improvisaciónes 1-3

- Enrique Granados:

- Piano Sonata #9 in B-flat, DLR VI:1.9 (arr. Scarlatti Sonata K190)

- Improvisación sobre "El Pelele"

- Danza Española #7

- Danza Española #10

Manuel de Falla, piano

Isaac Albéniz, piano

Enrique Granados, piano

1 Zuill Bailey, cello

2 Isabel Bayrakdarian, soprano

3 Milton Rubén Laufer, piano

Zenph ZS-1001 56:45

Summary for the Busy Executive: Spanish masters virtually resurrected, maybe.

I think most of us classical-music freaks fantasize what it would have been like to hear Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Liszt, and so on at the keyboard. Until time travel becomes practical outside of Star Trek, we can forget those performers born before the age of recording. Early recordings haven't the granularity to capture subtleties of performance. Most reproducing pianos also have problems capturing performer dynamics, touch, and so on. The Welte-Mignon system stood as a notable exception. Indeed, many composers – Debussy and Mahler among them – actually preferred Welte-Mignon to acoustic and early electric technology. The Welte-Mignon rolls have revealed worlds about certain composer-pianists, allowing us to see their music in a new light.

As I understand it, Zenph Studios has developed a method of capturing early acoustic and electrical recordings of pianists and translating them to a digital format, playable by a piano (here, a 1907 Steinway D) outfitted with a digital reproducing system. The translation process, according to Zenph, incorporates algorithms that analyze performance variables. So in effect, we have, thanks to the such a system, we can have high-quality recordings of a whole group of composers and pianists who performed in the era of low fidelity.

I have worked as a software designer and programmer, and I regard most claims of this sort skeptically. It's all very well to say that your analysis remains true to the performer, but in the absence of sufficient details, you can't really judge. As the old programming maxim goes, "Garbage in, garbage out." Also, I seem to have been slightly creeped out by the idea that no human hand has touched the keys, even at a remove – a kind of zombie music. At least Debussy actually put his hands on a Welte-Mignon keyboard.

On the other hand, this project has the imprimatur of producer Philip Amalong, a fine musician and pianist himself. The performances are terrific, if not necessarily authentic, and the sound is vibrant and exciting. I don't know what to think.

Albéniz and Granados won reputations as pianists – Falla, not so much. Consensus on their keyboard skills ranks Albéniz first, Granados second, Falla third. On the evidence of this CD, Albéniz produces the most subtle textures and colors, Granados the most finger-sparks, and Falla the most intense drama and crackling rhythm. Knowing absolutely nothing about piano technique (but I know what I like), I prefer Falla to the other two, but that may rise from my preference for his music over theirs.

I happen to own a recording of Granados's Welte-Mignon rolls (Pierian 0002) with three of the four pieces on the current program, so I decided to compare the incarnations. I listened to the recordings "blind." I had no idea which was Pierian and which Zenph. You'd think this would settle matters, but Granados apparently rarely played one of his pieces the same way twice (or with even the same notes). His performances actually differ from the published sheet music. The timings of the Danzas Españolas #7/#10 run from 4:20/3:51 (Welte-Mignon) to 3:04/3:07 (Zenph). The Zenph performances are fine, even distinguished, but the Pierians surpass them. For one thing, Granados seems to fashion a smoother, longer line in the latter, and the music breathes more.

However, his "arrangement" (more accurately, wholesale rewrite) of a Scarlatti sonata I've heard in an acoustic recording made for Odeón, the Welte-Mignon roll, and the Zenph system. The piano roll and the acoustic recording come from the same year, and the timings don't differ by more than seven seconds. Indeed, the acoustic recording may be the one that Zenph based its realization on. You can make out little more than the notes. The Odeón sound obscures almost all expressive characteristics. The Zenph recording swaggers, Granados apparently treating the score as an opportunity to wow. On the other hand, the Welte-Mignon roll retains the virtuosity while greatly expanding the color and the dynamic range. Again, remember that Granados made the roll with his very own fingers. Nobody had to infer the characteristics of his performance.

Pianist Milton Rubén Laufer plays Albéniz's La Vega – why, I'm not really sure, since the recreated performances were the point of the album. The liner notes mention that this particular version of the score came to light in 2007. Laufer does well enough, but keep in mind that both Alicia De Larrocha on EMI and Marc-André Hamelin on Hyperion have recorded some version of this piece.

Cellist Zuill Bailey and soprano Isabel Bayrakarian do amazingly well. Not only do they give fiery, colorful accounts, but they co-ordinate with the "ghost player" in a completely natural way. You forget that a computer-directed machine accompanies them.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz