The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Chopin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

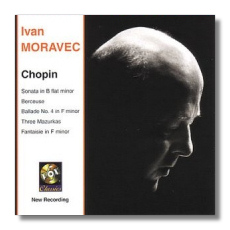

Frédéric Chopin

- Sonata in B Flat minor, Op. 35

- Berceuse, Op. 57

- Ballade #4 in F minor, Op. 52

- Mazurka in E Major, Op. 6/3

- Mazurka in B Flat minor, Op. 24/4

- Mazurka in D Flat Major, Op. 30/3

- Fantaisie in F minor, Op. 49

Ivan Moravec, piano

Vox VXP7908 64:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: Some of the best Chopin playing you will ever hear.

Moravec has long held the reputation of a musician's musician. In an age of flashy fingers and little else, he stands for the highest service to a composer's work. Artistically, he effaces himself almost completely. When I think of Moravec, I don't think of a musical instrument, but of a musical mind.

Chopin's music, like Bach's and Debussy's, can travel many different interpretive paths, but his performers tend to fall into two large categories. The first I could call the Individualists: those concerned with creating their Chopin. Extreme examples of this type might be Olsson and Argerich. The interpreters in the other category seem to "just play." The music sounds as if it comes to you directly from Chopin's brain. Rubinstein represents the archetype of this player. Of course, things aren't really so clear-cut. Players spread out along an interpretive spectrum. However, I should add that neither approach is inherently better than the other. Both have their pitfalls. In the first, the performer gets in the way of the music, rather than illuminates it. In the second, the performer makes no music at all.

Moravec, while definitely an individual, stands closer to Rubinstein than to Argerich. However, one hears more intention, more intellect if you will, in Moravec than in Rubinstein. Moravec gives the impression of more study than Rubinstein's "singing bird." Nevertheless, he also manages to convey the zaniness of Chopin's structural frame as well as clearly delineate it. This comes out most forcefully in the so-called "funeral-march" sonata, a piece which has confused many great musicians, including Schumann, who (although he enjoyed it) regarded it as a suite of Chopin's usual run of salon pieces, rather than a sonata. Shaw, however, admired the structure. Moravec plays through the first movement in such a way that justifies Chopin's designation. You can see why Chopin thought of it in terms of sonata form – the development of two subject groups of differing keys and character (in fact, a lot of Chopin's non-sonatas work this way). The sonata signposts are a bit mixed up, compared to Haydn almost willfully placed, but the sonata's essential point of contrast and development is kept. The second-movement scherzo, on the other hand, is almost classically chaste in its broad outlines, even though the new wine in the old bottle is pure Chopin. Moravec melts your heart in the trio, with a gorgeous singing line. Allusion to the trio, as in some of Beethoven's symphonic scherzos, briefly turns up in the coda.

I may have listened to the slow movement funeral march too many times to really hear it. It's certainly a bold stroke, but it seems to me very difficult to shape. Some pianists turn it into Mussorgsky's "Bydlo" from Pictures, making the procession approach and recede in one long span. I admit the effectiveness of the strategy, but it's become a cliché and, in the first place, not what Chopin wrote. Moravec manages to follow the score and keep interest. The fleet finale, lasting less than two minutes, is a wonder, with harmony and tonality largely in shreds. Moravec shapes it. One other thing: Moravec has a fantastic sense of harmonic movement and voice-leading. He almost never just plays chords. Whether from deliberation or instinct, he manages to string together constituent notes of successive chords to give you a line, wholly unexpected. This ability first attracted me to Moravec's work. He was playing (I think) the Liszt sixth Hungarian Rhapsody. By emphasizing the bass line near strategic cadences, he transformed the usual showpiece into real music.

The Berceuse, with the Bolero, is a genuine Chopin rarity. Not only did Chopin write only one, but you can see why pianists avoid it – "simple" music of horrendous interpretive difficulty. Its main problem is that it almost never changes key or significantly varies the left hand. In that regard, it's almost minimalist. How do you keep interest? Moravec does so by hesitating at the right moments – the ones where the possibility of change becomes apparent, thus building in a necessary, though low-key tension (this is, after all, a lullaby) as you wonder about the outcome.

I find the fourth the most ruminative of Chopin's ballades. This sort of thing is right up Moravec's street. Compared to some players I've heard, Moravec understates things. Those of you wanting your Chopin sautéed in chicken fat should avoid this. For me, however, Moravec makes the passion of the piece more convincing, rather than less. The quick parts of the piece are less an occasion for shock and awe at the grapeshot fired from the fingers than for building an argument. In short, the fireworks don't interrupt the reverie as much as they show the other side of it.

The mazurkas are fun. Moravec takes the opening of the first in a way that connects with Bartók's piano dances, with shifting accents. The second is a delicate marvel, without slipping into the fey. Moravec manages to hint at an underlying steel, without becoming pushy. This elegant restraint runs over into the third mazurka. The hesitations in phrasing are distinct, but never overdone. To me, this is a model of rubato.

My favorite work (and my favorite performance) on the CD is the f-minor Fantaisie. In too many hands, it doesn't come off as much of anything, except noodling around. Moravec delivers a powerful, moving account, making you feel the pianistic ornaments as an intensification, rather than a dissipation, of emotion. It's a difficult work, in the sense that Chopin shifts emotional gears on a dime. Moravec matches him and creates one gigantic, almost phantasmagoric span.

The recording has a touch more bass than I like, but only if I listen for it. Mostly, I'm too caught up in Moravec's music-making to notice.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz