The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vivaldi Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

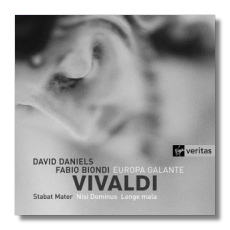

Antonio Vivaldi

Choral Works

- Stabat Mater, RV 621

- Nisi Dominus, RV 608

- Longe mala, umbrae, terroris, RV 629

David Daniels, countertenor

Europa Galante/Fabio Biondi

Virgin Veritas 5 45474 2 DDD 55:25

Vivaldi's early career as a composer was devoted mostly to instrumental works. Then, in 1712, when Vivaldi was in his mid-30s, he was commissioned to write the Stabat Mater included here for the church of Santa María della Pace in Brescia. Current scholarship indicates that it was his first sacred work. Then as now, the singer was a male, although we don't know whether he was a castrato or a countertenor. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this Stabat Mater doesn't feature the soloist at the expense of the instrumentalists, whose music is nevertheless kept to a modest scale. Modesty also figures in the work's thematic content, as the music of the first three sections is recycled in the second three. Virtuoso display and extreme emotion are absent in this work, which is attractive, balanced, and above all, devout.

The Nisi Dominus was written in 1717, during the period when Vivaldi, either by luck or by subtle political calculation, had been given the prestigious position of interim choirmaster at the Ospedale della Pietà, the same institution where he already had been teaching and composing instrumental music. In contrast to the Stabat Mater, this music was almost certainly written for a woman, probably one of the students at the Ospedale. Also in contrast, it is a more varied work, dramatically speaking; the soloist alternately expresses fear, awe, satisfaction, and joy at the Lord's strength. Irresistible opportunities for word-painting include the brilliant runs at "Sicut sagittae in manu potentis" ("As arrows in the hand of a powerful man") and a lullaby-like siciliano at "Cum dederit dilectis suis somnum" ("For he gives sleep to his beloved children").

It is uncertain who first performed the motet Longe mala, umbrae, terroris (Long-standing ills, shadows, terrors), which was written in 1725. He or she must have been quite a virtuoso. In the furious first movement, Vivaldi unleashes these and other afflictions ("wars, woundings, rages, furies," and so on) to music of staggering floridity. After a short recitative-like section, the work concludes with a calm plea for deliverance and a serene Alleluia. In less than 14 minutes, Vivaldi takes the singer (and the listener) from the fires of Hell to the joys of Heaven.

Few singers could do justice to this motet. David Daniels shows why he is rapidly becoming the preeminent countertenor of the current decade with this recording. His voice retains its evenness in all registers, and he cleanly articulates Vivaldi's most difficult runs and fioriture. In the other two works, he consistently makes a favorable impression with his tone, and with his sensitive yet lively interpretations. One of the most interesting things about Daniels is that his voice retains its masculine character no matter how high he sings. Compare him to Jochen Kowalski on Philips Classics and the difference is immediately noticeable.

Kowalski is partnered by a larger ensemble than the one that accompanies Daniels. On this recording, seven members of Europa Galante are listed, including conductor Fabio Biondi, who also plays the viola d'amore. Original instruments are used. As we have come to expect from Biondi's earlier Vivaldi discs, there is nothing reticent or modest about his accompaniments. As a result, an interesting and not unpleasant dynamic is created between Daniels and Europa Galante.

This recording was made at the American Academy of Arts and Letters in August 2001. Perhaps the engineers have placed the balance too much in favor of Daniels's voice, but it's not a major fault.

Copyright © 2002, Ray Tuttle