The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Mozart Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Wolfgang Mozart

Piano Quartets

- Piano Quartet in G minor, K. 478

- Piano Quartet in E Flat Major, K. 493

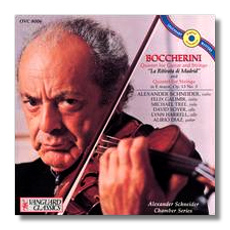

Alexander Schneider, violin

Michael Tree, viola

David Soyer, cello

Peter Serkin, piano

Vanguard Classics OVC8007

Like most terms, "chamber music" has meant different things at different times. From the late Baroque through the early Classical era, it served mainly as leisure for amateurs. After all, much was commissioned for the use of a patron. Franz Joseph Haydn's baryton trios, for example, written for Prince Esterházy to play, probably demonstrate this principle most clearly. Composers usually pursued virtuosity elsewhere – in the solo or concerted work which showed them off performing on their chosen instrument, in the elaborate orchestral work (usually orchestral suites; later on, symphonies), and in public music like opera and church pieces. Haydn, so often the key figure in the transition to new forms and – just as important – to new contexts for old forms, began to demand a higher level of ability not only in the chamber works like the piano trios (where, presumably, he played the keyboard part), but also in the string quartets, with their obvious connections to the series of symphonies, as opposed to formally simpler dance suites.

Mozart, in his mature chamber works, not only made Haydn's demands for more skilled players, but added something new, even modern: a new attitude toward the function of chamber music. For the performers, chamber music was still leisure and social activity; Mozart added something for the composer, who now wrote to express an inner seriousness (though not necessarily solemnity) of purpose. This corresponds to the literary movement of Romanticism, where the public forms of epic and drama give way to the interior lyric as the central poetic form. Chamber music similarly moves from divertissement to meditation.

Mozart seems to have invented the piano quartet. No one has found examples among his contemporaries or immediate predecessors, not even in Haydn, a prolific inventor of new instrumental combinations. Mozart left only these two examples, but they count among the very best. I say this, by the way, as someone who doesn't automatically swoon at the mention of Mozart's name. I'm not wild about the classical idiom in general, and a lot of Mozart bores the bejabbers out of me. However, Mozart and G minor go together like pan-fried chicken and oyster dressing. Furthermore, the technical problems of the combination – how to keep instrumental independence, how to give the cello or viola something interesting to do not already played by the violin or piano – Mozart has solved apparently without breaking a sweat.

This G minor and the one in the String Quintet, K. 516 both share a stormy urgency, which culminates in the Symphony #40, also in G minor. The first movement is full of memorable themes (at least one a major-mode variation on the opening theme), but it's really the development where the action happens. Textbooks usually call the development a "free fantasia on the major themes." This is true, but in this work, the definition misses the point. Rather than treat the development as an occasion merely to display his powers of invention, Mozart comes up with a dramatic structure, in which "we lose ourselves to find ourselves." In other words, we stray so far from our point of origin, that the matter of our return becomes an element of tension. How will he lead us back? Several times, the opening theme intrudes on the development, only to give way to other material. In a ten-minute movement, we arrive on solid ground only in the last minute or so, so it's a cliff-hanger. The second movement begins by playing elegant games with shifting accents and downbeats, so you only occasionally glimpse where in the measure you are. The third movement initially tries to convince you of its naïvete, with an extremely simple announcement of the main, rondo-like theme in the piano. The strings' immediate restatement, however, blows away that impression. In fact (although I haven't checked), it seems to be an "anti-rondo." Instead of episodes alternating with one or two main themes (a rondo, in words), a small group of ideas seem to occur in more or less the same order. It turns out not quite that simple, of course. For one thing, you're never quite sure when the initial theme will return. Mozart sets up transitional passages based on the idea and then switches you to something else. Also, the passages corresponding to "episodes" seem to have caught the bug of sonata development.

I apologize for going on so about the formal features of the work, but they do strike me as remarkable – revolutionary even – and as such at odds not only with Wolfgang the Powdered Wig Boy view of the composer, but also with the view that allows the listener a pro forma obeisance to Greatness before switching off the brain. In the interest of space, I'll avoid doing the same for the Eb quartet, although it's mind-altering as well, even though it approaches structure completely differently.

Alexander Schneider and company made a wonderful series of recordings which explored the chamber repertoire for Vanguard in the 60s. David Soyer and Michael Tree went on to the Guarnieri String Quartet. Peter Serkin emerged as one of the brilliant chamber players and contemporary advocates of his generation. Schneider, however, set the style of the performance – essentially, Romantic, a continuation of his Budapest String Quartet. I don't doubt that HIP (historically-informed performance) advocates would find this performance too Brahmsian, but, frankly, that's what I like about it. Unlike their unquestioned success in orchestral and choral repertoire, HIP-sters really haven't made the same march through the centuries in chamber music. They seem confined to continuo and earlier styles. I propose two reasons for this: the conflict between public, virtuoso styles and private, inner-light ones. Virtuosity, almost by definition, functions publically – it wants to impress somebody – and as such, it is more particularly rooted in its own time. After all, what you can do with an instrument depends in large part on the instrument you have. Neither the modern violin nor the modern piano is Mozart's.

We can also see this dependency in acting styles. John Gielgud, acknowledged as the great Shakespearean actor of his generation, in his recorded readings from the 30s comes off almost as a parody today. Similarly, it is very hard to watch Ronald Coleman and Leslie Howard movies. They're so stylized (a style perfectly acceptable sixty years ago) that you fight the urge to smack them into something more sensible – that is, more attuned to present sensibility. Thanks mainly to the movies, acting has become less a matter of public declamation and more one of communicating interior states. Actors no longer seek to create ideal types, but naturalistic ones. Musical virtuosi usually stick to their time as well. As much as I admire Wanda Landowska (especially her powers of invention), Pablo Casals, or Josef Lhévinne, I have to "think myself back" to listen to them. I'm always conscious of a gap between then and now, even though I think "now" has lost some of the value of "then."

Since Mozart, however, chamber music has moved from the realm of public expression to private, and, just as drama has striven to recreate the private and become more conventionally naturalist, so has chamber music. We seem not to want the music filtered through any historical style but our own. In other words, we do Brahms and Mozart piano quartets in the same way. The historically-informed stylistic filter we feel as a barrier to receiving the spirit of this music. It would be like listening to Shakespeare recited in a scholar-created approximation of Elizabethan English.

Consequently, I not only feel no reservation about Schneider's adoption of a Brahmsian style to Mozart, I welcome it. Furthermore, Schneider and his cohorts avoid the fey, walking-on-eggshells approach to Mozart playing and rip into it. They allow you to feel both the momentary vigor of the musical ideas and the drama in the overall architecture. Actually, with musicians of this caliber, the style they adopt means very little, and while I have serious reservation about such an approach to the grand choral and symphonic works, it seems right here, and it emphasizes the power – rather than the other-worldly beauty – of Mozart's musical mind. This is superior chamber-music playing.

The sound seems typical of the 60s – a bit bright according to present taste – but it is still quite acceptable.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz