The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

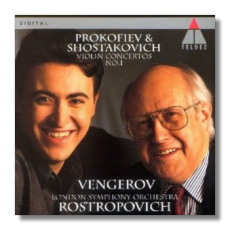

Prokofieff / Shostakovich

Violin Concertos

- Serge Prokofieff: Violin Concerto #1 in D Major, Op. 19 (1913)

- Dmitri Shostakovich: Violin Concerto #1 in A minor, Op. 99 (1955)

Maxim Vengerov, violin

London Symphony Orchestra/Mstislav Rostropovich

Teldec 92256 62min

Ever since the publication of Testimony, the supposed memoirs of Shostakovich, there has been a serious reassessment of his music by performers and critics alike. Double meanings and new depth have been found in nearly every work – especially those written at about the time of the Second World War. Thus, what we used to consider bland is now revealed to be a brilliant satire on the evils of Stalinism. And those merry, often banal finales that Shostakovich relentlessly churned out to satisfy the requirements of the Socialist Realist doctrine are suddenly found to contain dark, ominous overtones. Naturally, much of this is pure nonsense. Bad music is still bad music, whether it's a parody of a murderous dictator or a commercial jingle. Nonetheless, our understanding of some Shostakovich scores benefits considerably from our new knowledge of the composer's intentions. The First Violin Concerto is a powerful example. As Bernd Feuchtner points out in his excellent notes for this recording, "The concerto is a compendium of hidden messages which the composer systematically incorporated into his music as a means of communicating his moral resistance to the musically sensitive listener." Feuchtner might have added that sensitive performers like Rostropovich and Vengerov make these long hidden messages clear and unequivocal at last.

From the ink black darkness and desolation of the opening nocturne to the nightmarish apparitions and intense bitterness of the concluding burleske, Vengerov is in complete command. His interpretation boasts tremendous sensitivity to Shostakovich's wild mood swings as well as a breathtaking technique. Moreover, his dusky tone is perfectly suited to this eerie, haunted music. The level of tension that soloist and conductor generate in I is all but unbearable. Vengerov spins Shostakovich's long, sinuous melodic lines seamlessly, as if singing a moving and deeply personal lament. Rostropovich, meanwhile, brings a Mahlerian depth and symphonic richness to the orchestral accompaniment that adds immeasurably to the effect. The wailing and inconsolable grief of Oistrakh (on Monitor) comes close to matching Vengerov, but the young upstart is both more volatile and compelling. In II, Vengerov tears at the music in anger, employing rough, percussive bowing and slashing attacks that suggest the demented and threatening world of Bernard Herrmann's Psycho score (written more than a decade after this concerto). You can almost hear the bones rattle as the ghosts of Stalin's victims dance to the devilish fiddler. Indeed, it chills my blood all over again to listen to it as I type this. Following this harrowing experience, III comes as a gentle elegy, a tender consolation to the survivors of II's grim reaper. Vengerov sings out in a very heart-warming manner, becoming more ardent as this movement continues. The atmosphere of forced gaiety that permeates IV is captured wonderfully by Vengerov, who is far more effective than Oistrakh in exploiting the ironic sub-text. Vengerov venomously spits out the notes, demonstrating as he did in II that he is more concerned with exposing the composer's tormented sothan merely producing beautiful sound for its own sake. Indeed, the harshness of his playing helps convey the underlying hopelessness and desolation that permeates this finale. Vengerov's profound understanding of every note of this work is nothing short of astounding. No one – not even Oistrakh – can approach him in this concerto.

A radiantly lyrical version of Prokofieff's First Violin Concerto completes an excellent program. In this intensely personal reading Vengerov displays all the qualities of a master storyteller. While there are more demonically possessed versions in the catalog (such as Mutter, also with Rostropovich, on Erato), this one has a special timeless quality. Rostropovich once again proves an ideal partner, revealing every delicious detail of Prokofieff's inventive scoring without ever calling undue attention to himself (though he uncovers a startling flute sfortzando near the beginning of II that still surprises me every time I hear it). The crystalline clarity of Teldec's recording ensures that every orchestral solo is easily heard. The violin has been very closely miked and given rather more prominence than it would typically have in the concert hall. This ensures that every scrape and scratch of Vengerov's bow (and there are quite a few) is audible and that the soloist is never smothered by the orchestra. A very special recording that belongs in the collection of anyone with even a passing interest in 20th century Russian music.

Copyright © 1998, Tom Godell