The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

DVD Review

DVD Review

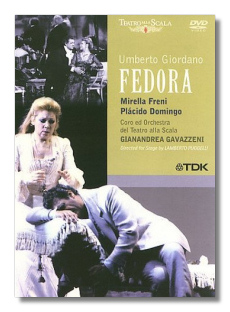

Umberto Giordano

Fedora

- Mirella Freni (Fedora Romazoff)

- Plácido Domingo (Loris Ipanoff)

- Adelina Scarabelli (Olga Sukarew)

- Alessandro Corbelli (De Siriex)

- Luigi Roni (Cirillo)

Orchestra & Chorus of the Teatro alla Scala/Gianandrea Gavazzeni

TDK DVWW-OPFED DVD 113 minutes Fullscreen Dolby Digital DTS

It's easy to dismiss Fedora on several levels. Yes, it is Giordano's "other" opera – i.e., neither as famous nor as successful as Andrea Chenier. Furthermore, its plot is incredible and melodramatic, and it is no surprise that it was adapted from a play by Victorien Sardou, he of Tosca, which Puccini later made into a "shabby little shocker" of his own. Also, it has been called a "one tune opera," the tune in question being Loris's aria "Amor ti vieta" in Act Two. (This is not fair. I find Fedora very tuneful, although it really is not a "numbers opera.") Still, give it a good cast, and approach it with a willingness to suspend disbelief, and its faded wiles can seem potent indeed. This is particularly true in its final pages, which make the handkerchiefs come out faster than you can say "La bohème."

Fedora Romazoff is a Russian princess engaged to wed Count Vladimir, playboy son of the Imperial Chief of Police. We never hear from him, however, as he is shot around the time that the audience is taking its seats. Fedora sets out to avenge his death, and when she extracts a confession from Count Loris (who in the meantime has become smitten with her), she denounces him in a letter to Vladimir's father. Then she discovers that Loris shot Vladimir not for political reasons, but because Vladimir was fooling around on the side with Wanda, Loris's own erstwhile amour. Joyously, Fedora then returns Loris's declaration of love, and they run off to Switzerland together. It is there that the chickens come home to roost, however. Loris finds out that his brother died in jail after being accused – nonsensically, it turns out – of complicity in Vladimir's death. Hearing the bad news, Loris's mother died on the spot. Loris realizes that the "mystery woman" who had denounced him and killed both his brother and his mother was Fedora herself. Understandably, he flies into a rage. Overcome with guilt and grief, she drinks poison from a hollow crucifix hanging around her neck (!). As she rapidly fails, Loris forgives her, but it is too late, and she dies in his arms as the song of a shepherd boy drifts down from the Alpine foothills. If you're not crying by then, then you're not paying attention!

The title role gives a good verismo performer something to sink her teeth into. Magda Olivero was one of the great Fedoras of recent times. Maria Callas also performed it at La Scala, and unusually, a tape of one or more of those performances has yet to surface. The present performance from La Scala, recorded live in May 1993, finds Freni in her late fifties and Domingo, as the hot-headed Loris, in his early fifties. They both look pretty good, and are convincing in their roles. He still sounds like a power-house, and there is little about his singing here to make one wish that he was 20 years younger. Freni's voice is no longer as fresh as it once was, but still, hers is an awesome performance in every way. Freni is a classy woman, and she can parlay some of that class into creating a suitably regal character. Individually, both singers deliver the goods. Together, they spur each other to even greater heights, and both the Act Two love duet and the Act Three death scene are examples of operatic craft at its most magical. This is what creates opera fanatics.

The rest of the cast gives excellent support. Scarabelli is adorable as Fedora's friend, the flighty Countess Olga, and Alessandro Corbelli is suave and mocking in his role as the French diplomat who warns Fedora in Act Three that her honeymoon is about to come to an end. In Act One, there is a powerful little arioso for Cirillo (Kiril), Vladimir's coachman, who after describing his master's shooting, kisses the hem of Fedora's skirt. Very "Old Russia"! Luigi Roni makes the most of this vignette. Gavazzeni conducts the score like the pro he is, earning the well-deserved cheers of the audience.

I'm not sure I like the other aspects of this production so much. Luisa Spinatelli's sets feature spectacular illuminated backdrops, but then she haphazardly places in front of them furniture which looks like it might have come from à La Scala garage sale. The furniture and the singers are placed on a turntable during Act Three, but it hardly rotates, so don't ask me what the point is. Lamberto Puggelli's direction is clumsy in proportion to the number of people on stage at any given moment. Why the dead Vladimir was brought back onstage at the end of Act One, only to be ignored by the cast, also is unclear to me. Puggelli also directed the video, and there are some clumsy moments here too, although the cameras generally are where they should be.

The sound is in the three usual formats, and a full-screen image has been used. Both are clean, clear, and have a substantial impact. The English subtitles are a little archaic in style, but they work well enough.

Copyright © 2007, Raymond Tuttle