The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Brahms Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

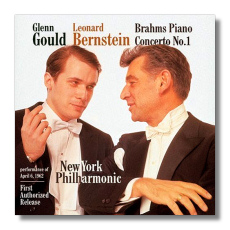

Johannes Brahms

Piano Concerto #1 in D minor, Op. 15

Glenn Gould, piano

New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

Live recording: April 6, 1962

Sony Classical SK60675 ADD 61:23

It must have been one of the stranger Philharmonic concerts in New York history. On the evening of April 6, 1962, Music Director Leonard Bernstein stepped onto the stage of Carnegie Hall, not, as the audience expected, to conduct Brahms' First Piano Concerto, but to give a little introductory speech. "Don't be frightened," he began. "Mr. Gould is here…." Bernstein and soloist Glenn Gould, it seems, had had a great difference of opinion regarding matters of interpretation, notably tempo, during rehearsals for this performance. Instead of opting out of the performance (or getting rid of Gould), Bernstein decided to swallow his objections and proceed anyway because of the great respect that he had for Gould's musicianship. Or so he said! Nevertheless, he felt the need to deliver the audience a disclaimer before bringing Gould out on stage.

Perhaps this is an example of having one's cake and eating it too. Perhaps it is nothing more than a particularly bizarre example of showmanship. This was not a foreign concept to Bernstein, after all, and now there are those who argue that Gould was not as pure as he might have wanted to seem in this area. Whatever the case, the music critics had a field day with both the performance and the extramusical circumstances. This performance has been in demand for more than 25 years, and its official release by Sony and the New York Philharmonic (Bernstein's introduction included) makes it accessible to more listeners than ever before. Now they can judge for themselves whether this is a valid Brahms First, a musical scandal, or something in between.

It's a slow performance to be sure, but it's not that slow. The movement timings are 25:49, 13:45, and 13:47, respectively. When Bernstein recorded the concerto 21 years later with Krystian Zimerman, the timings were 24:35, 16:28, and 13:00 – actually slower overall. Emil Gilels's recording with Eugen Jochum, which many critics regard as definitive, plays for 24:04, 14:44, and 12:33. Gould's divergences from the printed score are relatively minor – hardly on the level of a Stokowski – but like Stokowski, he illuminates the music by rethinking aspects of the score that many performers take for granted. For example, he can take a phrase, and, by altering the emphasis on a single note, give the phrase a surprising new meaning. There's no denying that this is a mammoth interpretation of Brahms' First Piano Concerto, but I find it faithful to my understanding of what this concerto is all about. If it lacks anything, it's a touch of vulnerability.

Because this is a live recording and never was intended for commercial release, one shouldn't expect the performance to be ideally polished. However, it is surprisingly free from faults (unless one faults its artistic conception overall). Similarly, the sound is not optimal, but it is very listenable. The disc closes with a brief excerpt (3:45) from a radio interview that Gould had with James Fassett the following year. In it, the pianist offers a tantalizing taste of his some of his musical philosophies.

This, then, is an interesting, even fascinating document. It's not the circus act that 27 years of story-telling have made it out to be. It shouldn't be anyone's sole Brahms First, but it has something to offer anyone who loves this music or who admires the pianist or the conductor.

Copyright © 1999, Raymond Tuttle