The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Gershwin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

George Gershwin

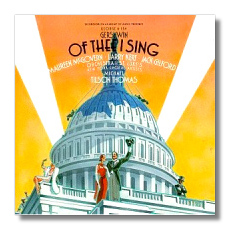

Of Thee I Sing / Let Em Eat Cake

Larry Kert

Maureen McGovern

Jack Gilford

Paige O'Hara

Jack Dabdoub

Orchestra of St. Luke's/Michael Tilson Thomas

Sony M2K42522

Gershwin performance stands in about the same place as Bruckner performance a few decades ago. Not only have the popular songs been arranged to a fare-thee-well, but the concert works have been silently "emended" by publishers. The same thing holds, by the way, for the Tchaikovsky symphonies, and this for an orchestrator revered - perhaps mere lip service after all - as a master. Textual scholarship applies not only to Renaissance masses or Schubert symphonies but also to music pretty near our own time. Gershwin especially has not been allowed to fail on his own. Someone always seems to know better.

Of Thee I Sing was probably the most sophisticated musical of its time, the first to win a Pulitzer (George Gershwin was the only one of its creators excluded by the committee, the jerks). Furthermore, as wonderful as Of Thee I Sing is, Let 'Em Eat Cake surpasses it, at least musically. This shouldn't surprise us, because Gershwin learned fast. Each one of his large works taught him something. He never fell back and never repeated himself.

All the acclaim, however, did not prevent both pieces from disappearing - at least in their original form. Samuel French, owner of the performing rights, butchered the book with horrid little updates and, probably without thinking twice (or once), reorchestrated the numbers. On television around 1972, Carroll O'Connor and Cloris Leachman appeared in a witless adaptation ("based on" the play), and yet again the music arranger (Peter Matz) cut down the original elaborate scenes for reasons best known to himself. I remember the reviews, most of which blamed the likes of George S. Kaufman, Morrie Ryskind, and Ira Gershwin because most hadn't seen or read or played through the original. I still have the lp of this, which I drag out now and again when I want to raise my blood pressure.

From that nadir until now, Gershwin's music has undergone a mini-boom, as far as scholarship is concerned. Yet, the current hum of activity would not have been possible, had the so-called Secaucus Trunk remained unopened in a Warner Brothers warehouse. They found, among other things, complete scores, missing numbers, original orchestrations, and so on. Also, Ira Gershwin's archives were turned over to the Library of Congress, and Ira had saved a hell of a lot. It is now possible for researchers to study Gershwin songs in manuscript (among new findings: Gershwin notated complete piano parts to almost every song). John McGlinn released a revelatory CD of Gershwin Broadway overtures and sequences from the film A Damsel in Distress (EMI CDC7479772). Three major recordings of the complete Porgy and Bess appeared within five years of each other. Gerard Schwarz had led a recorded performance of the première version of An American in Paris (interesting, although Gershwin's subsequent cuts strengthened the piece considerably).

Still, the work of Tommy Krasker reconstructing the Broadway shows has not only given us back national treasures in their original (or near-as-damnit) glory, but has forced a major re-evaluation of American theater history.

A great deal of loose writing has been unleashed about the origin of the "book musical" - in the most prevalent version, dating it from Oklahoma - as if the previous thirty years had been little more than revue sketches. There is something to be said for this view in regard to many teens and 20s musicals, including some of Gershwin's. The songs can be mixed and matched among shows, and in fact this has been done in revivals. The love songs and the novelties are a bit generic. You really don't have to know the dramatic situation to appreciate "I Got Rhythm," but you might find scene and situation impinging on "The Surrey with the Fringe on TOp." Nevertheless, the close relation between music and book had been around since at least Victor Herbert. Show Boat introduced the non-operetta musical on a serious subject, but the music's function was still essentially unchanged. What all these musicals have in common is the idea of dialogue leading to a "number" - choral, solo, or duet. François Villon makes a speech against the Duke of Burgundy and then launches into "Sons of toil and danger," which essentially reinforces the dramatic points just made. To use Monteverdi's distinction: the music does not advance the drama; the music comments on it.

In the "Of Thee I Sing" trilogy (Strike Up the Band - first version - Of Thee I Sing, and Let Em Eat Cake), we see something else at work. The main musical unit becomes increasingly not the song or number, but the entire scene. Music moves the drama along, much as the Act I finales to Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado and Iolanthe do, both of which introduce important plot points. In Of Thee I Sing, the Act I finale introduces the major complication (Wintergreen's choosing Mary Turner over Diana Devereaux), and the Act II finale resolves it. This is not done through the usual 32-bar song but by a musical tapestry that slips in and out of recitative, arioso, and song. You can see this in the trilogy by simply observing how much more sheer stuff the Gershwins contributed than is usual for a Broadway show. By the time he gets to Let Em Eat Cake, Gershwin has command of all the technique he needs for grand opera. It now comes down to a matter of a different kind of book.

The political satire of the trilogy, while not as harsh or as analytical as the contemporary German Zeitopern or especially the European stage works of Kurt Weill, still has considerable point. Strike Up the Band accuses American industry of promoting war to raise profits (actually, American industry has since found a way to sell weapons and yet stop short of promoting war). Of Thee I Sing chronicles politics without substance and by slogan. Let Em Eat Cake has some very dark fun with 30s totalitarianism and the contemporary American flirtation with revolution. In fact, all three shows demonstrate how fragile and precious democracy really is.

Krasker tracked down all the extant original orchestrations (by William Daly, Robert Russell Bennett, and one number - "Hello, Good Morning" - by Gershwin himself) and filled in the rest with orchestrations by my new hero, Russell Warner. The original Let Em Eat Cake orchestrations have been lost. Warner, with considerable knowledge of the style and considerable wit, worked from Gershwin's piano score. I certainly can't tell his arrangements from Daly's or Bennett's, which means that I can suspend disbelief and enjoy "pure Gershwin."

Tilson Thomas turns in his best Gershwin reading to date - vivacious, danceable - with no little fidgets of "personality" that marred his previous outings. The Orchestra of St. Luke's sounds as full as the Philharmonic. I do quibble with the casting. Larry Kert as Wintergreen sounds vocally tired, and Maureen McGovern's Mary Turner seems to be on the brink of turning into a pine board. Her voice is pinched and her line readings sound as if controlled from the Mother Ship. On the other hand, Jack Gilford, an actor known to bewitch audiences the moment he steps on stage or opens his mouth, lights up the entire recording as probably the best Vice President Alexander Throttlebottom ever (and, no, I haven't forgotten Victor Moore) - a mixture of haplessness and backstabbing stealth, and as dangerous (and loveable) as creme brulée. His musical roll call of the Senate is a sweet soft-shoe. His "Comes the revolution, everything is jake. / Comes the revolution, we'll be eating cake" manages fluff, fatuousness, and simplehearted, simpleminded joy. Paige O'Hara as Diana Devereaux manages to conjure up a slinky, comic femme fatale on the major make, almost entirely through her voice. By the way, her main musical tag is a startling adumbration of "Summertime." Apparently, the motif meant the Sultry South to Gershwin. Jack Dabdoub turns in a vital performance as the French ambassador in my single favorite part of the entire trilogy: "She's the illegitimate daughter / of an illegitimate son / of an illegitimate nephew / of Napoleon." Wow.

I can't recommend the entire Krasker series highly enough. However, there seems to be some time constraint on its availability. Girl Crazy came and went. Here are the labels and numbers:

- Girl Crazy: Mauceri, cond. Elektra Nonesuch 9 79250-2

- Strike Up the Band (first version): Mauceri, cond. Elektra Nonesuch 9 79273-2

- Lady, Be Good!: Stern, cond. Elektra Nonesuch 9 79304-2.

Outstanding. A personal favorite - Pardon My English: Stern, cond. Elektra Nonesuch 9 79338-2

- Oh, Kay!: Stern, cond. Elektra Nonesuch 9 79361-2

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz