The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Byrd Reviews

Farnaby Reviews

R. Johnson Reviews

M. Locke Reviews

Matteis Reviews

Purcell Reviews

Veracini Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

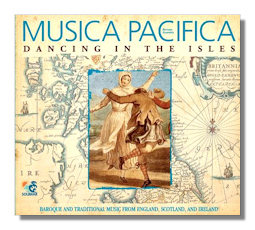

Dancing in the Isles

Baroque and Traditional Music

from England, Scotland, and Ireland

- William Byrd: La Volta

- James Oswald:

- 3 Trio Sonatas on Scots Tunes - Sonata in D Major

- Matthew Locke: Broken Consort, I - Suite #4 in C minor

- Nicola Matteis: Ayres in G Major

- Francesco Veracini:

- Sonata in A Major, Op. 2 #9 "Scozzese"

- Henry Purcell: 3 Parts upon a Ground

- Traditional British tunes and dances

Musica Pacifica Baroque Ensemble

Solimar 001 (700261311821) 74:58

Summary for the Busy Executive: From James to George.

This CD brings together different forms of mostly British secular music, high and low, from the Jacobean Renaissance to the early and middle Baroque. In the Renaissance, the main forms were sacred and vocal. The passage to the Baroque saw more focus on secular and instrumental. The program begins with country dances collected by publisher John Playford in his fabulously profitable collection The English Dancing Master (1650), essentially a "fake book" for musicians who played at popular, perhaps even low-rent dances. Many of the tunes survive today. However, it consists of melodies only – no harmonies, no other parts. It takes talented folks to arrange them. I've heard lots of arrangements, from the so-so to the extraordinary Sally Logemann and Marshall Barron. Musica Pacifica bases its fine arrangements on Barron, among others.

We move on to music for masques, usually an activity of the nobility or at least the very wealthy. Here, we also get keyboard pieces by William Byrd and Giles Farnaby from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (c. 1605).

The 18th century went on a bender for things Celtic. This is, after all, the time of the mania for "Ossian." Scottish and Irish tunes became especially popular. Scottish dancing master, publisher, and promoter James Oswald produced a collection of compositions based on Scottish tunes, of which the four-movement sonata is one. Far from trying to regularize the vernacular tunes, Oswald keeps their modes and irregular phrasing and charms with the "antique" result.

Musica Pacifica violinist Elizabeth Blumenstock beautifully arranges the traditional tunes in a faux-naïve way. With a few instruments, she gets great color variety.

Teacher of Purcell, Matthew Locke was perhaps the most prominent British composer of his day. Known for his testiness of temper, he saw himself as a defender of British musical tradition against the newfangled musical notions coming from France and Italy. His music still retains some connection to the Elizabethan fantasia and madrigal (especially in his counterpoint), as well as to the masques of the English court. The Suite #4 for "broken consort" is marked by quick mood swings and turns of thought. The final movement is a sarabande in a lively tempo, the first of its kind I've heard. Apparently, the sarabande slowed down as it went along.

Nicola Matteis brings to mind London as a profitable stop for touring virtuosi. An Italian guitarist, violinist, and composer, Matteis arrived in London around 1670 and stayed in England until he died. After some years of neglect, he came to notice by playing at private musical gatherings, around 1674. The diarist John Evelyn exclaimed:

I heard that stupendious Violin Signor Nicholao (with other rare Musitians) whom certainly never mortal man Exceeded on that instrument: he had a stroak so sweete, & made it speake like the Voice of a man; & when he pleased, like a Consort of severall Instruments: he did wonders upon a Note: was an excellent composer also … nothing approch'd the Violin in Nicholas hand: he seem'd to be spirtato'd & plaied such ravishing things on a ground as astonish'd us all.

In Matteis's music, you see a shift in English taste to continental productions. You get something typical of the music of the Italian Baroque violin-composers. Every melody instrument gets treated like a violin, with violin figurations making up a good part of the passage-work.

Veracini, another Italian violin virtuoso, toured all over Europe but finally established his home base in Florence. He was so good that he may have had to leave Dresden due to a plot by other violinists to kill him. He created a sensation in London, and Burney wrote that "There was no concert now without a solo on the violin by Veracini." Most considered him either the first- or second-greatest violinist of his time. Like the traveling virtuosos of the 19th century, Veracini was astute enough to capitalize on the local fondness for "national airs," a way of saying to the audience, "It's great to be here in Sandusky." The "Scozzese" ("Scottish") varies the tune "Tweed Side."

We end on Purcell's "Three Parts upon a Ground," an acknowledged masterpiece. It's a Purcellian "chacony," a repeating bass over which all sorts of ingenious canonic tricks are played and the harmonies stretch away from the implications of the bass line almost to the breaking point. It sounds effortless.

The Musica Pacifica Baroque Ensemble plays with both liveliness and a heap of suave. As appropriate for dances, they get the feet moving. Where they need to arrange, they do so with great elegance. If you want to give yourself a refreshing break from, say, Bruckner, I recommend this.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz.