The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Lassus Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

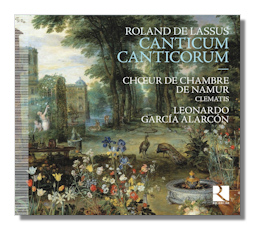

Roland de Lassus

Canticum Canticorum

- Osculetur me osculo

- Veni in hortum meum

- Tota pulchra es, amica mea

- Vulnerasti cor meum

- Surge propera amica mea et veni

- Quam pulchra es

- Veni dilecte mi

- Audi dulcis amica mea

- Magnificat super ancor che col partire di Cipriano à 5

- Missa super Susanne un jour

Clematis

Choeur De Chambre De Namur/Leonardo Garcia Alarcón

Ricercar RIC370

The Choeur De Chambre De Namur with Clematis (both Belgian) directed by Leonardo Garcia Alarcón on the enterprising Ricercar label give an excellent performance of the "Song of Songs", Canticum Canticorum, together with the Mass for five voices, "Susanne un jour", and a Magnificat (on "Ancor che col partire" by Cipriano, also for five parts). They prove conclusively – if proof were needed – that Lassus (1532-1594) was a composer who could turn his hand to anything. And did.

One of the lines which the composer trod carefully was that which avoided falling foul of the strictures imposed by the Council Of Trent that the material on which masses should be based on suitable subjects: that is, to avoid themes or allusions which were in any way risqué – ideally not secular at all.

The Missa super Susanne un jour was published as part of a collection of Masses dated 1577, while the eight verses of the "Song of Songs" (which was deemed acceptable to the church despite its amorous intensity) appeared throughout the two or three decades on either side of the Mass. The Magnificat (actually the longest single piece on this CD) was probably composed for a wedding ceremony in 1568.

It's all beautiful, sumptuous yet restrained music which derives its impact as much from the originality of its melodic invention (listen to the Mass's "Agnus Dei" [tr.14], for instance) as from anything unduly spectacular or "invasive". The singers understand this and have approached the music as an effective vehicle for the expression of faith and adoration in the circumstances in which it was first heard; not as anything over-demonstrative.

The music is also almost always lively, energetic and positive, upward-looking in conception and composition. There is a corresponding lightness from the Namur Chamber Choeur. Theirs is a spirited, gentle and equally buoyant style of vocal (and in places instrumental) projection. There is no lack of engagement with the music. But their singing comes from the heart; and they are obviously enjoying it too. It's all very natural.

One striking aspect of the style which the singers bring to this glorious music is the superb balance between ensemble and the individual. The full membership of the Choir consists of four each of sopranos, countertenors, tenors and basses, different selections of singers from each of which participate in the various works. Their individual deliveries, though – however colored and distinct in pace and phrasing – complement and support a combined approach which presents Lassus' complex lines and rich textures in a highly pleasing and convincing manner.

The juxtaposition of high and low passages in the "credo" of the Mass [tr.12] is a good example. The ways in which the group interweaves lines re-inforce the confessional commitment which this movement represents. At the same time, Lassus would surely have us recognize that it is an individual who believes – not an idea or "object" or entity. Distinct singers' voices support such an equilibrium. What's more, the Choir's articulation of the all-important text (especially given those dictates from Trent) means that it is comprehension which is advanced, not effect.

The acoustic (of the St Sébastien Church in Stavelot, in the Belgian province of Liège) is delightfully resonant. It never obscures the rhythmical subtleties that add such richness to Lassus' sound world. Rather, it somehow offers the listener a sense of how powerful Lassus must have felt his inventions to be. The booklet has the complete texts in Latin and translation as well as a short essay setting the context for Lassus' composition by Jérôme Lejeune, the CD's artistic director and specialist responsible for recording and editing. There are other recordings – perhaps surprisingly – only of the Mass. So this set of performances almost recommends itself. Lassus does not always command the attention he deserves; the performers in this case have quietly, yet unambivalently, commended him to us. We should respond accordingly.

Copyright © 2016, Mark Sealey