The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

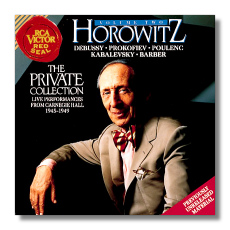

Vladimir Horowitz

The Private Collection, Volume 2

- Claude Debussy: Études, Book I (excerpts)

- Serge Prokofieff: Cinderella - Intermezzo & Valse lente

- Francis Poulenc: Intermezzo #2; Novelette #1

- Dmitri Kabalevsky: Préludes, Op. 38 (excerpts); Sonata #2

- Samuel Barber: Excursions, #1, 2 & 4

Vladimir Horowitz, piano

RCA 09026-62644-2

The 1940s saw Horowitz's career at its probable peak. He seemed to play everywhere (his status as Toscanini's son-in-law didn't hurt). To many, he represented the pianist, just as Toscanini, Heifetz, and Casals represented the conductor, the violinist, and the cellist. Horowitz eclipsed pianists as good, like Rubinstein, Gieseking, Serkin, and Horszowski, just as Casals eclipsed Feuermann. You get some of this in the hagiographic bent of the otherwise-admirable John Pfeiffer's liner notes. To some extent, audience fascination arose from a myth of technical perfection ("Horowitz never played wrong notes") as somehow a sign of superior musicianship and from the fact that the war had kept leading European musicians from appearing in the major American musical centers. For me, Horowitz was always more than a pianistic freak or pristine automaton. He possessed a patrician musical mind, evidenced by his gorgeous recordings of the Mozart Sonata #12 and of his classic Scarlatti. I believe that Horowitz felt trapped by his own myth, and this was one factor leading to his forsaking live performance during the 50s and early 60s.

Considering the last phase of his career, when he fell back on his bedrock repertory, I must admit that I forgot the amount of modern music he played. In fact, it surprised me a little. Scriabin and Debussy remained in his programs, although in his last years the Scriabin tended to the "Chopin" Scriabin and the Debussy of the lighter, popular works. Excepting the Debussy Études, most of the music here comes under the category of party pieces.

Some regard Debussy's music as moonlight, water, perfume, and the faint sounds of Spanish guitars - a mere sensualist. However, in the last decade or so of his life, Debussy's music became far more austere than the voluptuous Rêverie and Clair de lune would lead one to suspect. In fact, his works appeared more often in Schoenberg's private concerts in Vienna than those of any other composer. For one thing, he came under the influence of Stravinsky - only fair, since only a few years earlier, he had decisively turned Stravinsky from Rimskian nationalism to a modernist path. The Études, in two books, came about through Debussy's love of Chopin (he produced an edition of Chopin's piano works). Indeed, Chopin and Debussy are just about the only composers of études whose sets are simultaneously real studies of various aspects of pianism and real music. Each of Debussy's études concentrates on one aspect of technique: #4 (playing sixths), #1 (playing runs without cross-overs and -unders), and the sublimely odd #6 for 8 fingers (no thumbs!). #4 begins languidly but moves into some fast repeated notes and takes an extensive tour of all the ways sixths can be produced among ten digits. #1 starts as a witty take-off on Czerny five-finger exercises, but immediately takes off for the harmonic aether and dances a manic gigue. #6 is famous as an exercise in perversity: a ripping toccata for 8 fingers (I wonder how many pianists cheat). In contrast to what I believe current practice, Horowitz plays these as modern music, without overlaying a schmier of "absinthe and fog." These performances have a bright edge, emphasizing the new sounds, indeed the "new-ness" of the sounds. Odd note clusters splash across the tonal sky like fireworks in Étude #1. Étude #8 seems to teeter on a harmonically unstable ledge as the Horowitz fingers (no thumbs) run break-neck over the keyboard.

Horowitz was friendly with the Soviet consul stationed in New York (who defected some time around the early 50s) and, from that connection, premièred many contemporary Russian works. The Prokofieff transcriptions from his own Cinderella ballet proclaim that composer from the opening bars. Horowitz also gave the American premières of Prokofieff's Sonatas 6 through 8, and left a blistering recorded account of #7. The Cinderella excerpts are slighter, although they work beautifully in the complete ballet, but still bewitching. The Kabalevsky aims for more and accomplishes less - curiously "faceless" music, at best a pale reflection of Shostakovich or the Prokofieff of the Sarcasms.

With the exception of his Theme et Variee, Poulenc's music for solo piano has no ambition other than to charm. They take a musician, rather than a virtuoso, even though Poulenc himself played extremely well. His virtuoso writing for the instrument, curiously enough, went mainly into his accompaniments, as in the opening to his song cycle La Fraicheur et le Feu. The two pieces here unashamedly recall the Chopin of the salon, with melodies of sweet nostalgia and occasionally dripping with schmalz. Horowitz has an odd affinity for this music - odd, because I, for one, normally think of him as an essentially "cool" executant, non-revealing of self. He can certainly whip up fireworks and excitement, but even his Chopin wins, not by its fire or its "personal slant," but by its elegance. Poulenc used to remark that most pianists played him too dry, mistaking him for Stravinsky or Milhaud. "Food goes better with a good sauce," he would say as he constantly urged pianists to more pedal. Certainly, the music here benefits from it, and, wonder of wonders, Horowitz does press down the sustaining pedal more here than in other works, stepping right up to the line of overpedaling, and here and there stepping over. But they are two incredibly beautiful accounts. Poulenc had the last word on all those who called him inconsequential. True, he shied away from the great vistas of Mahler and Schoenberg. Yet at his most shamelessly sentimental, he became most human and most profound.

Horowitz also connected with American composer Samuel Barber, recording what remains an outstanding performance of the Piano Sonata. As he did with Prokofieff, Horowitz also played chips from the American's workshop. Barber's Excursions are a rare step for this composer into 1940s Americana. Essentially, they are exercises in vernacular styles undertaken with Stravinskian distance: boogie-woogie, blues, cowboy, and mountain fiddle. Horowitz plays only three of the four movements, because that's all Barber gave him. Indeed, Schirmer originally published Excursions with only these three movements, but as I, II, and IV. Still, Horowitz never incorporated the third movement - sweet and petite variations on "Streets of Laredo" - in any of his programs. Horowitz, with the exception of the last movement (a barn dance by Faberge), hasn't got the idioms at all. The performance isn't all-out terrible, just curiously detached from native musical context. In the boogie-woogie, for example, Horowitz needs to emphasize the bass. Try to imagine boogie-woogie with a self-effacing left hand. Barber himself doesn't help matters. His boogie bears little resemblance to the power of Pete Johnson or the rough and dirty Meade Lux Lewis. This is high-class music going slumming, but in a good-natured way - without sarcasm or parody. The term "excursions" itself gives the game away. The composer is taking a vacation from the serious business of music. Indeed, Barber, in later life, deprecated these little charmers (and they do indeed charm) as "bagatelles." Fooey. They are their own excuse for being.

Horowitz made these discs for his own use, so don't expect commercial-quality sound. A thin patina of crackles lies over every track. The Debussy in particular sounds like someone is crinkling cellophane in front of the mike. Still, if you can put up with "historic" sound in glorious mono (of course), this disc provides much of interest.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz