The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bartók Reviews

Chopin Reviews

Lees Reviews

Liszt Reviews

Prokofieff Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

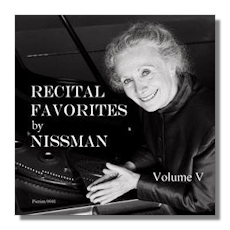

Recital Favorites

Volume 5

- Frédéric Chopin: Andante spianato & Grande Polonaise brillante, Op. 22

- Serge Prokofieff: Sonata #6, Op. 82

- Franz Liszt:

- 3 Concert Etudes, S. 144 #1-3

- Liebestraum #3

- Benjamin Lees: Odyssey #1

- Béla Bartók: Allegro barbaro

Barbara Nissman, piano

Pierian 41 73:38

Summary for the Busy Executive: Wonderful.

In this fifth volume of Barbara Nissman's projected ten-volume series of recitals, the pianist has set a particularly challenging program. By now, I should be used to seeing her Prokofieff and Liszt, but I always get a little buzz when I find them on the card. She does them so well.

The recital begins with one of my favorite Chopins, the Andante spianato and the Grande Polonaise brillante. A relatively early work, written in the composer's 20s, it pretty much encapsulates a good deal of Chopin's music – the serene, long breath as well as the driving dance. The composer discovered his artistic path fairly early. "Spianato" is an odd word, even in Italian. I know that it can mean "paved," "smoothed," or "evened out," and it may refer to the unruffled accompaniment over which Chopin spins a long melody, full of his characteristic arabesque. Unusually, it never leaves its home key. Its subsections distinguish themselves by changes in rhythm and texture, rather than by modulation. Chopin provides one contrasting idea to the main aria – chordal and seemingly bone-simple, little more than a cadence. You'd think something this simple would pose no difficulties at all.

How wrong you would be. I've heard a lot of pianists, including undoubtedly great ones, miss the mark over and over again. They either slow down to the point of somnolence or speed up to trivialization in the main aria. The little chordal passage can wreck an entire performance. It should melt your heart with its simplicity. Pianists tend to tart it up. The more successful tend to play the most straightforwardly, as is the case of one of my favorites, Horowitz in his live Carnegie Hall recital, one of the "returns." On the other hand, Rubinstein, normally a touchstone of such Chopin playing, doesn't seem to connect with the piece at all – straightforward past the line of prosaic. Michelangeli does superbly in the aria and fussily in the chordal statement. Richter takes everything so slowly, you'd think he was on heroin. I think I know why performers subject the piece to such horrors: its genuine depth tempts them to Significance.

Nissman is almost zen-like in this piece. The beauty seems so effortless, and she's so "in the zone," or Chopin's zone. She runs closer to Horowitz and to Michelangeli rather than to Richter, both in timing and in temperament. Nissman approaches her music with, I'd say, a "passionate classicism." She doesn't want the music to "speak for itself," exactly, but she does want it to speak – without inflation, an expressive collaboration between the composer and herself. The voice of the composer keeps her from wandering off into the outré. However, her own voice makes her readings personal. She began, I thought at first, a hair too fast, but she quickly convinced me. After all, her line is a living thing: it breathes. Tempo expands and contracts "naturally." Her rubato is absolutely gorgeous – among the best of any Chopin player I know. The little chordal passage – the sandbar that beaches so many readings – comes off as both simple and profound. Her Grande polonaise differs from that of many in that she emphasizes the "grande" less than the delicacy in the music. She still has plenty of power, usually reserved for the ends of large sections (with the coda the grandest of all), but also found in the minor-key episode. Equally impressive is her treatment of Chopin's ornaments. She reminds me of a jazz musician making it all up on the spot.

Nissman refers to the Prokofieff Sixth Sonata – the first of the three so-called "war" sonatas – as a symphony for the piano. This performance differs from her account in the complete cycle on Pierian 7/8/9, a reissue of Sony recordings. Nissman is a recognized authority on the composer's piano music. She was, if not the first, at least one of the early performers to give concert series of all ten. She has lived with this score a long time. Both recordings stand among the best of the best, so relative evaluations seem pointless. The overall timings lie in the same neighborhood. I find the later reading a bit more incisive, and, in any case the Pierian sound improves upon the Sony by quite a bit. The "war" sonatas, of course, represent a significant part of Prokofieff's reaction to the fighting on the Russian front during World War II. I find them quite distinct. The Seventh, the most concise, strikes me as the most psychologically distressed. The Eighth sounds mainly a meditative, retrospective note. A little loose, nevertheless for me it strikes the deepest. The Sixth seems to me the most Beethovenesque of the sonatas, and the sonata I have in mind is the "Hammerklavier," particularly the first movement, where Prokofieff not only creates an exciting musical argument, but manages to throw in other Beethoven references as well (for example, the opening of the Fifth Symphony). Yet all the allusions remain subtle, rather than in-your-face. The second movement, a characteristic Prokofieff gavotte, allows Nissman to feature her subtleties of touch, especially staccato. It wouldn't seem out of place in, say, Roméo and Juliet or Cinderella. It constantly suggests orchestral colors. I can say the same for the next movement, designated as a very slow waltz. I would call it my favorite of the sonata, but that sleights all the other movements. Here, Nissman once again impresses with her mastery of the singing line. She shapes, she phrases, she breathes. She imbues the line with such subtleties, again it reminds me of a living creature, and the textures are clear as water. The finale, a toccata, drives and leaves you gasping not only at its energy, but at the virtuosity it demands.

The Liszt concert etudes – "Il lamento" (lament), "La leggierezza" (levity), and "Uno sospiro" (a sigh) – show the influence of Chopin. Although published as a set, pianists often program them separately. Some disparage that part of Liszt's output unashamedly designed to wow, but not me. The mindset is so goofy that it charms and intrigues, and it leads to more "serious" work, like the Mephisto Waltz #1 and the visionary late music. They stem from the exploration and extension of piano technique and the willingness to visit bizarre neighborhoods. For these, however, Liszt has dialed down the outrageous. Again, although you can easily distinguish them from Chopin – they lack Chopin's characteristic "cool" – they lie somewhere between the opera paraphrases and the more abstract works, like the Sonata. "Il lamento" is less a deep, heart-felt lament and more of what you might hear from a troubadour and his lute. "La leggierezza" (levity, meaning lightness, rather than frivolity) reminds me of a shower of butterflies, and one can discern a touch of sadness in it as well, particularly at the very beginning and end. The start of "Uno sospiro" makes me think of an unruffled lake, but it quickly turns to romantic yearning, with a pentatonic idea that foretells early Debussy. Nissman gets more out of these pieces than any other pianist I've heard. Indeed, she raises the first two to a level I never thought they could reach. Performers do indeed make a difference.

Benjamin Lees wrote three "odysseys," years apart, the first for English pianist John Ogdon and the last two for Mirian Conti. When he had all three, he grouped them under the title Odyssey, rather than number them separately (available with on Toccata Classics69). I find them unusual in the Lees catalogue. The composer often got stuck with the label of Surrealist, mainly because when he lived in Paris, he hung around with that crowd of painters. However, it's very hard to be a musical surrealist. Most surrealistic pieces of music tend to be quite short and episodic, like those of Erik Satie and Lord Berners. Lees tended to large statements, and in fact most of his music displays extremely tight motific logic. An odyssey is, of course, a journey, often one where you don't know the goal or how you'll get there. Lees makes a musical analogy to a structure that has an argument, just not a normal motific one. Odyssey #1 proceeds gesturally, with heavy use of textures made up of octaves and fifths. The piece also holds together harmonically. One hears the same tonal qualities throughout. Psychologically, the work is "full of trouble." Nissman notes that despite the twists and turns, we end up where we began, and structurally, that is indeed the case. However, the unease at the beginning has been fleshed out. We understand better the nature of the psychic storm.

Bartók's Allegro barbaro origins lies in a nasty review from a French critic, who referred to the composer as one of the "young Hungarian barbarians." Bartók gave a rub-it-in-your-face response through this piece, which became one of his most popular solo piano works, if any of his solo piano scores can be called popular. The conservatism of contemporary impresarios and audiences tend to shut out even this work, written a century ago, 1911, slightly before Le sacre du printemps was even begun. The title really nails the character of the piece. At under three minutes, it had tremendous influence, launching such things as the Prokofieff Toccata and the vogue for "barbarism" among composers that lasted well into the Twenties. Just to confirm the fact that artists don't always pursue an orderly path of development, Bartók himself immediately fell back on a more Impressionist idiom. His own "barbaric" period gets going after World War I. At any rate, the piece combines folk dance with Modernist steel and muscle. I've heard pianist after pianist flail at it, and frankly the writing tempts them to do it. Nissman creates a reading as powerful as a modern locomotive, without rattle or bang – that is, purposeful, driven, without wasting energy. The poise of it paradoxically creates a more overwhelming effect.

We end with Liszt's third Liebestraum, the famous one. Indeed, it's so famous that for years I never realized there were two others. My favorite performance – if you can call it that – comes from a comedy recording by Victor Borge, who dumped all over the piece while playing it beautifully. I love this piece and feel not the slightest twinge of guilt. There's a little Wagner in it, particularly Tannhäuser, at least in process around the same time, but whether Wagner took from Liszt (as he surely did elsewhere) or Liszt from Wagner (the thefts were mutual), I can't say. All three Liebesträume have love poems as their inspiration. The poem on which the third is based talks about the grave and the enduring power of love. The endurance comes through; the grave, not so much, but I think it an important idea to keep in mind. A big tub of powdered sugar awaits the unwary pianist. This piece often dissolves into confection. Yet, it's not about the sweetness of love, but its strength – indeed, strong as death. Quite simply, Nissman nails it without turning it into a sermon. The rubato is both noticeable and "inevitable." You can imagine other great interpretations, but this one is individual and true to itself. It has enough romance for any adult.

Once again, I'd like to single out Nissman's production team: producer, recording engineer, and editor Bill Purse and piano technician David Barr, a wizard of the Steinway D. The piano tone has great depth and creaminess without sounding muffled. This is one of the best-recorded piano discs I've ever heard – simultaneously rich, spacious, and natural. What will these folks do next? I'm told a "Diabelli" is in the works. I'm getting anticipatory chills.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz