The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Debussy Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

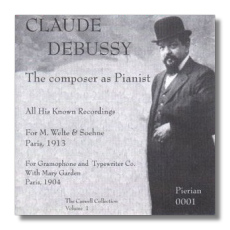

Claude Debussy

The Composer as Pianist

- from Préludes, Book I

- La plus que lente

- Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade

- Children's Corner

- D'un cahier d'esquisses

- Pelléas et Mélisande: Mes longs cheveux

- Ariettes Oubliées

Mary Garden, soprano

Claude Debussy, piano

Pierian 1 49:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: Revelations, and no fooling.

I can count my list of great composers for the keyboard on my fingers, with no necessity to resort to my toes: Bach, Scarlatti, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, Brahms, Debussy, Ravel, Gershwin, and Bartók. Your list will probably differ from mine. Composers make my list because, first, they show a new approach to the keyboard while true to the inherent nature of the instrument or because they bring an existing view to a new height, and, second, they write great music for the instrument. I've also noticed that most of these composers ask for an individual "set" of the hands – their music feels different to play – and their piano music can take a wide variety of interpretation. It would be nice to know, however, how Beethoven played his own sonatas.

Obviously, we don't get composers' interpretations until the age of recording. Yet, early on, most major composers wouldn't record on shellac because they hated the sound of the early rolls and platters. The two most widespread methods of mechanical reproduction (Ampico and Duo Art reproducing pianos) couldn't give back the subtleties of dynamics or a player's touch – at least, not without the aid of an intermediary technician, who marked down the dynamics on a score as the pianist played and then got them onto the roll later. As a young song-plugger and writer, Gershwin made many of these rolls, mostly for the money. They sound very little like the playing you hear on his 78s.

The third method of mechanical reproduction, the Welte-Mignon system, was the preference of many of these composers. Mahler and Granados made such rolls, as did Debussy, who, although he made conventional recordings, made far more Welte-Mignon piano rolls, in one 1913 session. The Welte-Mignon mechanism fit inside a piano – usually a Welte piano, but it could be custom-fit to others. The device differed from the familiar reproducing pianos in that it could reproduce not only dynamics but also touch and pedal technique, recorded directly from the pianists' actions. You also had the option of a mechanical "player," called a "Vorsetzer," which looked like a large ottoman, placed in front of – and probably covering – the keyboard. The problem with the system is its extreme fussiness. Different technicians in the modern era have produced different results. In this case, Pierian has used the talents of an engineer, Kenneth Caswell, who has devoted decades to studying the Welte mechanism. With his restored Welte reproducing piano, he has given the rolls a modern recording, and the results have won the imprimatur of Harold Schoenberg himself, formerly a severe critic of modern Welte-Mignon reproduction. That's good enough for me.

Given the importance of Debussy's piano music, as well as its popularity, I would consider this release one of the ten most important in the history of recording (please don't ask me for the other nine). You get an equivalent of having Bach play the Goldbergs for you. Now, many composers don't perform their own music all that well – perhaps one reason why they're so eager for somebody else to take on the performance. Debussy stands as one exception. His contemporaries remarked on the individuality not only of his music, but also of his piano playing. What strikes you from the opening track, Danseuses de Delphes ("dancers of Delphi"), is an extraordinary, even extreme, inwardness, practically a self-communion, as if the composer sings, or even hums, to himself. The first descending row of chords is just magic, raising the little hairs on the back of a listener's neck. La cathédrale engloutie ("the sunken cathedral") becomes surprisingly dramatic, with a large dynamic range, as the cathedral rises, apparently inexorably, from the sea. Indeed, Debussy at one point runs out of room: he simply can't get any louder. One can find more refined performances. The composer at times treats his music more roughly than what you usually hear from others. Minstrels, for example, lurches, the rhythm almost obliterated. On the other hand, Debussy seems at times to call for a delicacy beyond the capability of fingers or for a piano which has no hammers at all. La danse de Puck skitters around like sparks from a bonfire. All the playing, however, has a fabulous singing quality and steely sense of musical line – the sense that all notes, from first to last, connect one to another, as if the piano were really a string orchestra. La plus que lente shows Debussy's debt to Chopin in its mercurial shifts of tempo and of color.

I love the Children's Corner Suite best, mainly because I get it entire. "Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum" skims the musical surface like a skater, with mostly that super-delicate touch, but with bass notes occasionally accented, just to let you know that rock supports the filigree. The bass smoothes out considerably in the opening to "Jimbo's Lullaby," with that imaginative self-communion of a child (in this case, with a very deep voice) shutting out the world, while the main strain takes on the hypnotic quality of Ravel's "Laidronette." "Serenade of the Doll" and "The Snow is Dancing" manage to skip and caper, but smoothly. There's none of Horowitz's aggressive snap, for example. The heart of the performance comes in "The Little Shepherd," which sounds like the music from under the hill. "Golliwog's Cakewalk" is really my only disappointment, mainly because Debussy's syncopations are so sloppy. It's as if he tries too hard for eccentricity. On the other hand, D'un cahier d'esquisses, a piece that often gets routine performances, is a marvel of interpretation and refinement. There's plenty of heart in it as well, although Debussy doesn't wallow. Obviously, the piece meant more to the composer than to most of his interpreters.

We also get Debussy's acoustic recordings as Mary Garden's accompanist in the Ariettes oubliées ("forgotten ariettas") and in an extract from Pelléas. I find these more problematic than the rolls, mainly because the sound is so crummy. However, I probably make that judgment precisely because I have the rolls for comparison. Without Caswell's and Pierian's dedication, I'd have been extremely grateful for the acoustic recordings. Mary Garden, of course, was a favorite of Debussy, but it's not fair to judge her by these recordings. Her voice seems a little small and thin. Her virtues – precise intonation, fabulous musicianship, particularly in the Ariettes – nevertheless come through. The songs are tricky as hell, and none of the tricks seems to faze her. She's particularly breezy in "Green." The recording process (1904) fails completely to capture the subtle richness of Debussy's playing. It's as if you had water in your ears.

Pierian has several other discs I plan to review in the months ahead. They've done a great job so far.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz