The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Debussy Reviews

Ravel Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

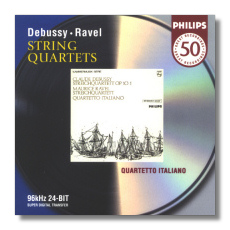

Debussy & Ravel

String Quartets

- Claude Debussy: String Quartet in G minor

- Maurice Ravel: String Quartet in F Major

Quartetto Italiano

Philips 464699-2 56:34

Summary for the Busy Executive: You probably won't find better.

It took French composers most of the nineteenth century to come up with a really good string quartet – Franck's example in 1888. Even so, Franck's German models – Schumann, Liszt, and Wagner – are pretty apparent. Debussy's string quartet appeared five years later. Most of Franck's followers hated it, which lets you know how radical the music must have seemed. While today we still see the lingering spores of German Romanticism in the work, it's still the first string quartet that sounds French, rather than Teutonic. The Teutonicism comes from a certain harmonic cast, particularly in the first movement, and in the approach to form. Once the first movement has passed, the Franconia shows itself in the quasi-modal shape of most of the themes, and most obviously in the scherzo second and slow third movements, where we stray rather far afield from Wagnerian modulations and immerse ourselves in the parallel chord progressions so characteristic of Debussy in particular and musical Impressionism in general. The slow movement dares much with bare textures, interrupting tutti passages with one instrument singing the remnant of a song. Further, for those who think of Debussy as dopey and moonstruck, the intellectual and architectural power of the quartet hits just as hard as its beauty. Every theme derives from the first idea, and Debussy can ring an apparently endless supply changes – some that take you to the limits of intelligibility, others breathtakingly and beautifully simple. The latter impresses me the most, particularly in the slow movement, where the tempo slows to barely moving and the counterpoint reduces almost, but not quite, to hymn. Above all, one encounters even at this early date that kaleidoscopic, subtle musical "psyche" so prevalent in the late works: En blanc et noir, the Villon ballads, and the cello sonata, for example. Franck called Debussy's scores "nerve-end music," and although he probably meant it as a slap, he pretty much got it. This isn't the Romanticism even of traders in the fantastic, like Hoffmann, Browning, Swinburne, or Poe, but very much a personality who revels in "unsettledness," who needs neither resolution nor transcendence. Debussy remarked that he wanted to write music "without sauerkraut." With this quartet, he got his wish.

The Ravel quartet comes almost a decade later. The Saint-Saëns first quartet intervenes, but that gives off mainly weak echoes of Mendelssohn. Ravel does something new – something not even Debussy achieved in his quartet. In a sense, Ravel takes a step backward – combining his thematic bits and pieces into mainly song-like forms. Debussy's quartet moves like a snake through the forest, tracing an unpredictable, yet in hindsight inevitable, path. The components tend to fall into place. The listener very seldom doubts his way. Ravel's quartet sings and dances. The modal implications of the melodies influence the harmonies. Ravel doesn't try to force them into a post-Wagnerian harmonic corset, as Debussy sometimes does. I can't come up with a more beautiful quartet than this one. I think of it as even profound, but in a very French sense. Influenced by the Austro-German masters, we tend to think of profundity as somehow "God-drunk." That is, the music wants to take us to infinite spaces and mountainous heights, ever-approaching (as Mahler has it in the Eighth) the divine throne. On the other hand, listening to the Ravel quartet is like being kissed by someone you love deeply and your realization, in that kiss, that you are loved in return. In short, you don't have to know God to be happy. Furthermore, there's brains as well as beauty in the work. As in the Debussy, just about every major idea relates to the opening measure, but Ravel goes about his business far more subtly. He conceals his art. It took me decades to realize, for example, that both the plucked pizzicato opening to the second-movement scherzo and the main idea of the third-movement adagio work changes on the very first theme of the entire work. Ravel dedicated the quartet to his teacher Fauré (yet another French master of chamber music, and a match for Ravel in compositional subtlety), but the older man didn't care for it. Fauré particularly singled out the last movement as "stunted, badly balanced, in fact a failure." About the only significant encouragement Ravel received came from Debussy, who pleaded with him not to change a note. To try to give Fauré his due, I think the finale the weakest movement because, in the light of the other three, it's the most conventional and probably the closest in its rhetoric to Debussy's quartet finale. At any rate, Ravel published the piece about five years later without revision. So there.

As you can probably tell, though I love the Debussy, I've gone ga-ga over the Ravel and have recordings of it from most of the major postwar ensembles – the Juilliard, the Melos, the Cleveland, the Emerson, the Guarneri, the Talich, and the Vlach, as well as two different recordings (three, if you count a better repressing) by the Quartetto Italiano. Keep in mind that I have a holy horror of duplicating pieces in my collection. Legendary New Yorker editor William Shawn once said something to the effect that the only time he believed in artistic perfection was when he listened to the Quartetto Italiano. To me, this performance runs so far ahead of even its splendid competition, it's hard not to agree. It's not even a matter of "imprinting," since I heard (and fell in love, I may add) the Juilliard first, roughly forty years ago. But that was probably a reaction to the pieces, since it didn't take me long to find performances I liked better. I've come to take the gorgeous string tone, precision of ensemble, and rhythmic bite for granted. Somehow, they wear the skin of these works. It's practically a spiritual exercise. The Debussy can sound almost clumsy under other bows. The Quartetto gives it incisive maturity. Their Ravel will break your heart, it's so beautiful.

The sound still has a bit of tape hiss (either that, or it's very bright acoustic), but that shouldn't stop you.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz