The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Prokofieff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

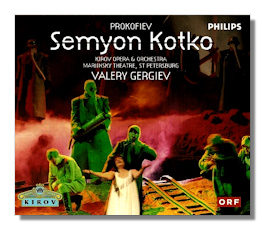

Serge Prokofieff

Semyon Kotko

- Viktor Lutsyuk (Semyon)

- Tatiana Pavlovskaya (Sofya)

- Gennady Bezzubenkov (Tkachenko)

- Yevgeny Nikitin (Remeniuk)

- Ekaterina Solovieva (Lyubka)

Mariinsky Theater, St. Petersburg

Valery Borisov, Chorus Master

Kirov Chorus and Orchestra/Valery Gergiev

Philips 464605-2 DDD 2CDs: 58:15, 78:31

The success of Semyon Kotko was crucial for Prokofieff's continued acceptance as a bona fide Soviet artist. He had spent all of the 1920s and a portion of the previous and succeeding decades in the decadent West, and when he came back to the USSR for good in the mid-1930s, he needed to work hard to convince the government that his heart and his political credentials were in the right place. Although the ballet Roméo and Juliet was produced in 1936, it didn't became a success until later productions, and the composer's attempts at frankly patriotic music fell afoul of the commissars. In 1938, a story by one Valentin Katayev titled I am the son of working people… came to his attention, and Prokofieff found what he had been looking for: an ideologically sound story, and yet also one that stimulated his creative juices, not least because of the Ukrainian setting. Katayev and Prokofieff prepared the libretto together, and the première took place in June 1940. (The arrest – and subsequent execution – of Semyon Kotko's stage director Vsevolod Meyerhold in 1939 could have put a damper on what turned out to be a good première for Prokofieff, who had to distance himself from Meyerhold to ensure it.)

Western audiences tend to assume that an opera that Soviet bureaucrats found ideologically sound can't be worth hearing. In truth, Semyon Kotko is a strong work, and its music is as interesting as its ideology is educational. The title character is a Ukrainian soldier home from the front in 1918. Upon his return he is regarded as a hero, and he rekindles his relationship with Sofya, whose father, Tkachenko, seems strangely opposed to their union. The first two acts depict Ukrainian village life, and the romantic ups and downs of Semyon, Sofya, and other young villagers. Then, at the end of Act Two, evil Germans suddenly show up and they, with the assistance of Tsarist loyalists (who include Tkachenko), begin to make life miserable for the villagers. Act Three ends powerfully, with the village in flames, good Soviet citizens hanging by their necks, and keening women, including one who is given a "mad scene" of sorts. In Act IV, Semyon, who has escaped, is hiding out in the forest with partisans waiting for orders from the Red Army. (These come hidden, of all places, inside a melon.) One detects subtle satire in a scene where Semyon instructs dull-witted partisans in the care and feeding of gun. Semyon hears that Sofya is about to be married off to a scummy loyalist, and when the orders from the Red Army come instructing him at attack the German HQ back at the village, he wastes no time in making a grand operatic rescue of both his sweetheart and his town. Unfortunately, he is captured in the town square. Just as he is about to be executed by Tkachenko, the Germans scurry out of town with the advance of the Red Army, and all the "good guys" sing a paean to the Ukraine and its fighting people. Curtain.

There are no arias or set-pieces in Semyon Kotko – there is little here to stop the show. What makes the opera strong, however, is its lightning-quick action and the characterization. In his essay to this set, Andrew Huth compares the libretto to a film shooting script, and he is right on the mark. This is an opera that keeps your eyes and ears moving. Although the characters are "types," Prokofieff finds music to make everyone an individual. He also is a master at establishing physical and emotional atmospheres, whether it be a forest at night, or the anguish felt by women who know their loved ones might be gunned down at any moment. There's little about the score that is memorable except for the overall impression that it makes, and that turns out to be very favorable indeed. This is one of those operas that is more than the sum of its parts. It might be Soviet hoo-hah, but it's good hoo-hah.

Gergiev and the Kirovians have been working their way through the Prokofieff canon; previous releases include The Fiery Angel, Betrothal in a Monastery, War and Peace, The Gambler, and Roméo and Juliet. (I look forward to Love for Three Oranges, and am curious about Story of a Real Man, which is supposed to be another politically correct pot-boiler.) This set was recorded in Vienna in cooperation with Austrian Radio during a series on concert performances in November 1999. The audiences are quiet, and, given the concert origins, stage noise is not a problem. (One suspects that this is a noisy opera to produce.) Gergiev's conducting is understanding, and the strong cast keeps characterization high. Lutsyuk is heldentenorish albeit a bit quavery; tenor Evgeny Akimov as a secondary lead has a brighter and more attractive voice. Filatova's Sofya is a bit of a twitterer, and the standout among the women is Solovieva, the one who gets the "mad scene" after her husband-to-be is hanged. Dark-voiced Bezzubenko is a sinister Tkachenko, and Nikitin makes a strong impression as the village's Kotuzov character.

The booklet contains a transliterated Russian text with an English translation, and Huth's excellent essay. I wish there were more photos of the Kirov's staged production, which, with its gasmasks and green lighting, looks intriguing.

Copyright © 2001, Raymond Tuttle