The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Poulenc Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

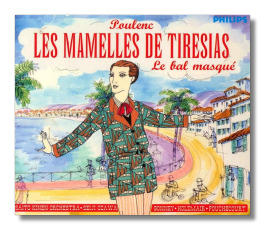

Francis Poulenc

Les mamelles de Tirésias

- Les mamelles de Tirésias 1

- Le bal masqué 2

1 Barbara Bonney (Thérèse)

1 Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (husband)

1 Wolfgang Holzmair (gendarme)

1 Tokyo Opera Singers

2 Wolfgang Holzmair (baritone)

Saito Kinen Orchestra/Seiji Ozawa

Philips 456604-2 72:20

Summary for the Busy Executive: Putting the "ooo" in "ooo-la-la."

These two works lie roughly fifteen years apart, Le bal masqué premiering in 1932 and Les mamelles in 1947. Poulenc conceived of Les mamelles as a diversion from his serious works of the war, notably the choral masterpiece La Figure humaine. For the opera, he returned to one of his earliest literary heroes, Guillaume Apollinaire, who exercised the greatest influence over the composer immediately following the First World War. Poulenc's music returns to his "bright" Satiean idiom of the Twenties. Indeed, when I first heard the opera (the Denise Duval LP), I thought it was from the Twenties. Naïvely I believed that composers "progressed." Surely, Poulenc had outgrown this sort of thing – a work of Dadaist hi-jinks. Poulenc did progress, in the sense that his work became increasingly assured technically, but a good deal of his career consists of a back-and-forth between an unashamed hedonism and a naïve, direct, and even stern Catholicism. Actually, it's probably more accurate to talk of an interpenetration of the two, particularly since key musical ideas appear in either kind of work.

Poulenc wrote all three of his operas – Les mamelles, Dialogues des Carmélites, and La Voix humaine – for the remarkable Denise Duval, a singing actress of great range, who got her start at the Folies-Bergère. Mamelles takes advantage of that aspect of her art. It's essentially a series of vaudeville comedy routines.

The piece also shows how Poulenc took over his texts. Apollinaire had written his skit as early as 1903, setting the action in "Zanzibar." Without changing a word, Poulenc shifted time and place to the French Riviera of the Twenties – for Poulenc, a magic place since childhood. The music and its vigorous pace call to mind the old René Clair musicals like Le Million and the early Chevalier movies like Love Me Tonight – the opera a high-class cousin, perhaps. But there's a serious undercurrent to the music at odds with the slapstick of the text, just as Apollinaire, apart from his joking, has some serious points to make. The prologue, for example, in which the moral is set forth ("France! Have more babies!"), is sung to music that would not have been out of place in Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmélites. Tiresias was, of course, the blind prophet who had the distinction of having lived as a man and as a woman. The myth goes that Tiresias saw two snakes mating, wounded the female, and became a woman himself (or now, herself). A number of years passed, when she saw the same two snakes. This time, she wounded the male and became a man again. By this point, we should be able to guess that Apollinaire wants to talk about gender.

Thérèse, a bored housewife, is sick of her confinement to the home. We get a more exact idea of how bored when she interprets her husband's calls for more bacon as lovemaking. She aspires to more than household drudge and recreation. She wishes to be a mathematician, a senator, a telegrapher, doctor, and so on, and so great is her frustration, that she wants to become everything at once. She opens her blouse, and her breasts, transformed into balloons float up. She explodes them with a cigarette, and begins to grow a beard and whiskers. Indeed, she becomes hairier than her rather meek little milquetoast of a husband. Once she shaves, she transforms into an elegant young man, gives herself the name Tiresias, and sets off on a great career as everything she wants to become.

The deserted husband meanwhile reasons that wealth is children. He determines to have children without the need of a woman and manufactures 40,049 babies in a single day. Almost all of them have great careers, and he lives off their income. But all is not ideal. The sudden huge population increase has put a great strain on the resources of Zanzibar. Thérèse returns with the knowledge that she is dissatisfied. All the careers in the world haven't made up for the love she has missed. She woos her husband and transforms back into a young woman. The couple reunite – not without the husband lamenting the loss of her breasts ("Bah!" she replies, "Don't complicate matters") – and the opera ends with a grand chorus advising people to "scratch if it itches."

One can, of course, see the work as sexist, but I think Apollinaire is up to something else, or at least more. What's wrong with the separate careers of husband and wife is not the gender reversal, but the fact that they are separate – a denial of love as well as of sex. Civilization gets in the way again. Convention makes Thérèse unhappy enough to forsake love. Forsaking love in pursuit of synthetic utopias also raises serious problems. Apollinaire ends his play in essentially one giant Prélude to lovemaking as all the women snuggle up to all the men and various actors invite the audience to join in. Poulenc ends his opera with a grand chorus, which alternates between a sultry waltz and a kick of satyr's heels, a hymn to "make babies!"

In Le bal masqué, Poulenc again re-creates an imaginary Riviera. The previous year, he had composed the song cycle 5 Poems of Max Jacob. Jacob, a French Jew, converted to Catholicism and, in Ned Rorem's phrase, "became more Catholic than the Pope." It didn't help him. He died in a concentration camp. The verses of Le bal masqué come from the 1921 collection Le laboratoire central. It interests me that while the verses Poulenc chose are highly acerbic satire, the music he wrote is so full of fun and so good-natured. There's an innocence that brings to mind a child making up songs about what he's doing or seeing at that moment. Poulenc's café instrumentation (piano, violin, cello, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, drum kit, and comedy percussion) emphasizes the René Clair side of Poulenc's musical personality. Much of the Jacob verse uses puns and near-puns ("le Comte d'Artois," "sur le toit," and "compte d'ardoises" – "the Count of Artois," "on the roof," and "count the slates," respectively). There doesn't seem to be an exact musical equivalent, but it does give Poulenc a certain license for outrageousness. Again, there's the curious appearance of musical ideas that attain fuller expressive scope in later, more serious work, like the organ concerto and the Dialogues, but they don't appear in the serious-sounding sections of this "profane cantata." Poulenc does throw an impressive curve ball, amidst the cutting-up, with the song "La dame aveugle" ("the blind woman"), a piece which sounds like an update of Schubert's lacerating "Die Krähe" – incidentally, one of Poulenc's favorite songs. Why it appears in such a sunny work I leave to better guessers. The cantata finale comes loaded with a funny surprise.

Ozawa's Poulenc has hitherto been almost criminally clueless, with truly bad recordings of the Gloria and the Stabat mater, among others. Here, he does a superb job. Fluke? You be the judge. Holzmair continues a minor tradition of great Germanophones performing La bal. Fischer-Dieskau and Wolfgang Sawallisch made a very fine recording of Le bal, with an equally fine Fauré La bonne chanson, and Holzmair and Ozawa at least match them. In fact, I find Holzmair's reading less up-tight emotionally and almost as accurate as Fischer-Dieskau's. The recorded sound is what most of us would consider acceptable, without calling attention to itself. If you don't have these works, this is a very good choice indeed.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz