The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Saint-Saëns Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

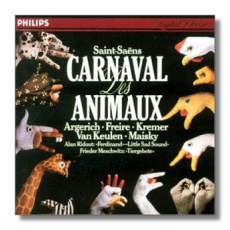

Argerich & Friends

Le Carnaval des animaux

- Camille Saint-Saëns: Le Carnaval des animaux

- Frieder Meschwitz: Tier-Gebete

- Godfrey Ridout:

- Ferdinand

- Little Sad Sound

Martha Argerich & Nelson Freire, pianos

Gidon Kremer & Isabelle van Keulen, violins

Mischa Maisky, cello

Philips 416841-2 62:17

Summary for the Busy Executive: A masterpiece and three musical rice cakes.

Camille Saint-Saëns wrote a prodigious amount of music, in every genre. To me, you can have all of it except the Danse macabre, the late sonatas for wind instruments, and especially Le Carnaval des animaux, and I think the last his masterpiece – ironic, since he allowed only one number from it, "Le cygne," to be published during his very long lifetime. I love every single number, including "The Swan," the most conventional part of the suite. Every other movement seems adventurous, "outside the box," more than not only "The Swan," but more than anything else in Saint-Saëns's output. Surely "Aquarium" is Debussian Impressionism before the fact of "Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun." The rest of it is fun and high spirits, and you can't get enough of that in classical music, where we tend to pull long faces and await transcendence over this "black Aceldama of sorrow." If a good time wasn't beneath Mozart in his Figaro overture, it's certainly not beneath me.

The question really comes down to which carnival we want. Encouraged by André Kostelanetz (who seems to have been inspired by the dubious proposition that enjoyment plus enjoyment equals more enjoyment), Ogden Nash, a poet people either love or hate (I can do both simultaneously), wrote verses to the suite in 1954. Nash, I think, almost always wrote his best about animals. A favorite of mine is the one about the cow:

The cow is of the bovine ilk;

One end is moo, the other, milk.

I like his verses for Carnaval on their own, but they annoy me when performed with Saint-Saëns's "zoological fantasy." To me, they get in the way of the music. So I pretty much write off every performance with a narrator (almost always a terrible reader besides). The one exception is Stokowski's with the classy Basil Rathbone as the narrator, (available on the Avid label). Stokowski really gets what this music is about. He understands the jokey nature of it, and the dissonance between Rathbone's British clip and Nash's breezily American verse delights, mainly because Rathbone understands the wit of the dissonance. On a slightly lower level is Prêtre, who leads a very elegant (très French) performance, sans récitant, on EMI.

How well do Argerich and her sandbox buddies do? Mainly, I like the chamber size of the performance, the original context of the piece (a private at-home party, I believe). Everything is clear. Rhythms spring. Individuals get to leave their cherry bombs on the doorstep or to sing beautifully. Argerich and Freire, for example, outrageously mug up "Pianistes," rhythmically pulling the pianos ever more wildly out of sync, and then bringing them back together with a bang at the "coda." Irena Grafenauer's flute chirps merrily in "Volières." Eduard Brunner on clarinet emits the cuckoo's cry from the middle of the deep woods. I've rarely heard it sound so lonely. Overall, the performance blends extremely high musicianship with kiddie rough-house.

The other three works are melodramas – that is, music written to accompany a speaker. To me, this genre usually doesn't work. Either the music makes the words unnecessary, or the words the music. The examples that worked on me the best have been Schwantner's New Morning for the World and Prokofieff's Peter and the Wolf, although I keep longing in my heart of hearts to hear the Prokofieff without the words. Ridout and Meschwitz use wonderful, even classic, texts which relegate the music to the realm of the superfluous. Ridout's Ferdinand, for speaker and solo violin, is based on Munro Leaf's tale of Ferdinand the Bull (illustrations by Robert Lawson, one of my favorites when I first began to read; I took out every Lawson book from the Cleveland Public Library. It turns out I do judge a book by its cover). Gidon Kremer plays the violin, so the music gets every chance. The speaker, pianist Elena Bashkirova, just blows him away, with a pitch-perfect reading and a Russian accent as thick as Natasha Fatale's. Meschwitz's Tier-Gebete (animal prayers), for speaker and piano, take beautiful poems by one Carmen Bernos de Gasztold, depicting animals praying to the Almighty. The best way to convey their flavor is to quote:

Prayer of the Ox

There was once a time when animals could talk. And so they went before their Creator with a prayer, so they could tell him what they had in their hearts. Each in his own way. The ox began:

Lord, give me some time. Men are always so frazzled. Let them understand that I simply can't be rushed. Give me time to chew. Give me time to put one foot in front of the other. Give me time to sleep. Give me time to meditate. Amen.

The music arouses even less interest on its own than Ridout's for Ferdinand, but it's a decent accompaniment. Kremer and Bashkirova divide the duties of the narrator. Kremer is fine, but Bashkirova will amaze you in the range and depth of her characterizations. Her mouse is a bundle of nerves jangling at high speed. Her cat conveys regal condescension, sensuousness, and a willingness to tolerate you if only you had the minimum intelligence to see things her way. Bashkirova could give lessons to professional actors, and she plays the piano, too. The only problem is that you need the pitter-patter of little Teutonophones about the house, since the texts are all in German and the notes give no translation.

Ridout appears again with Little Sad Sound, for speaker and double-bass. The text is annoyingly whimsical, but – who knows? – a child going through an infatuation with Shirley Temple might enjoy it. Once again, the music counts for nothing – in this case, less than nothing; it's even more the handmaid of the text than in Ferdinand. However, Kremer hams it up with good humor and without patronizing. Children should appreciate his efforts, as they tune out the music.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz