The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Cage Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

DVD-Audio Review

DVD-Audio Review

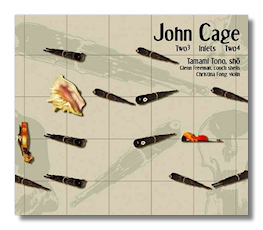

John Cage

- Two3

- Inlets

- Two4

Tamami Tono, sho

Glenn Freeman, conch shells

Christina Fong, violin

OgreOgress Audio DVD 634479370557 157:33 96kHz/24-bit LPCM Stereo

In 1990, John Cage met sho virtuoso Mayumi Miyata and wrote several works for her. What, you are asking, is the sho? One might think of it as the ancient Japanese version of the harmonica. It is more than a millennium old, and it was used in gagaku, the music of the Japanese imperial courts. As with the harmonica, those who play the sho usually produce several notes at one time, and because sound is produced whether the player is exhaling or inhaling, the instrument is useful in providing (literally) long-breathed accompaniments. Miyata demonstrated the sho's viability in contemporary classical music, and Cage certainly is not the only composer to have written music for it.

Probably conch shells also have served as musical instruments for at least as long as the sho. As they come directly from nature, they are considerably simpler than the sho, yet it is possible to modulate their sounds to a degree by inserting one's hand into them while blowing them, or by partially filling them with water. No doubt Cage was attracted to both of these instruments not just because of their cultural associations, but also because there is an element of irreproducibility or randomness in how they are played. A sho can be played for only so long before moisture collects in its tiny pipes; it must then be put aside (and sometimes heated) until the moisture evaporates. A conch shell is even less controllable. When it contains water, if it is tipped one way or another, a liquid gurgle is the result. Some might consider that a liability, but Cage welcomed it as part of the music, to the extent that the performance itself was part of the composition.

Two3 and Two4, both composed in 1991, are among Cage's so-called "number pieces." As indicated by their titles, they are the third and fourth number pieces that Cage composed for two players. Two3 is for sho and conch shells, and Two4 is for sho and violin. The former work is in ten sections, each at least ten minutes in length. The latter is three or four sections, depending on which instrument you are playing (!), for a total playing time of 30 minutes. In both works, Cage has given the performers guidelines (partly derived from chance operations) for what they will play, but the performers also contribute to the "finished" work. It is unlikely that there will be two identical performances of Two3 and Two4.

Both works challenge the listener, asking him or her to throw out traditional preconceptions about everything that music is supposed to "do." Melody, in the usual sense of the word, is absent. The pace is so slow that a pulse is obscured, and harmony plays no structural role. In fact, the music doesn't adhere to any traditional structures; it starts, continues, and stops, without any feeling of tension and release, or of narrative. It is best, then, simply to let the music "happen" to you, which is why listening at home probably is ideal.

Inlets (1977) is for conch shells alone, and is seven minutes of burbling and bubbling, and an occasional trumpeting. It is interesting how the sounds produced by the shells sound like African drums. Again, don't expect a listening experience that makes sense in any traditional way. Even asking yourself whether or not it is pretty probably is irrelevant. I do find that it has a certain fascination. I wonder if Glenn Freeman would consider posting a video of himself playing the conch shells on YouTube; I'd love to see how this is done.

With this repertoire, there's no such thing as a definitive performance, but neither Tono, Freeman, nor Fong leave one worrying about the music's untapped potentials.

The audio DVD medium allows one to hear all 121 minutes of Two3 without changing discs – a clear advantage. "Clear" also describes the 96kHz, 24-bit engineering. OgreOgress discs are available through cdbaby.com.

Copyright © 2008, Raymond Tuttle