The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weinberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

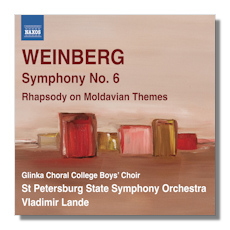

Mieczysław Weinberg

- Symphony #6, Op. 79 (1963) *

- Rhapsody on Moldavian Themes, Op. 47 #1 (1949)

* Glinka Choral College Boys' Choir

St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra/Vladimir Lande

Naxos 8.572779 61min

Those who follow developing trends in concert halls across the globe will know that the music of Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996) is getting a fair amount of attention of late. And undoubtedly among the reasons it is drawing notice is that it is quite dynamic and actually sounds familiar, some would say suspiciously familiar. Indeed, many musicologists and listeners have noted a stylistic similarity to Shostakovich. But is it fair to say that Weinberg was mainly an imitator of his older compatriot's style? Well, there are definite similarities where Weinberg could easily be mistaken for Shostakovich. But then there are passages in Hummel that sound like Beethoven and in Chopin that are very similar to piano music by Weber. I doubt, however, you could call Hummel and Chopin manqués, respectively, of Beethoven and Weber. That said, it must be conceded that Weinberg does owe a sizable debt to Shostakovich, because the similarities occur not just as passing moments but as lingering passages, where harmonies and instrumentation carry undeniable characteristics of Shostakovich. I could go to cite stylistic similarities in the Sixth Symphony here (or in the Fifth or Twelfth) to make the case, but the case has already been made.

Having written all this, one might expect a negative report on Weinberg here. But, nay, I can still say that Weinberg must be assessed as a composer of considerable talent. He wrote music in all genres but was especially prolific in, perhaps not so coincidentally, the two genres that Shostakovich was busiest in, the quartet and symphony. Weinberg produced seventeen string quartets and twenty-two symphonies (more or less) and perhaps a few of his works will get into or near the fringes of the standard repertory. I would guess the Sixth Symphony here might well be a candidate for such consideration. It is a dark work, with a long first movement filled with tension and emotional turmoil. A flute solo in the latter half is ghostly and very reminiscent of Shostakovich, and the movement ends with the tension unresolved. But a powerful impression is left.

There are three middle movements approximately half as long (seven to eight minutes each) and a finale of about ten minutes in length. The second, fourth and fifth movements feature a boys chorus, and the first of these is quite colorful and rhythmic, with a text on youthful subjects by Lev Kvitko, who by the way was executed by the Soviets in 1952 apparently because of his dissident views. The paranoid Stalin (and his KGB crony Lavrenti Beria) needed little reason to take out anyone who posed the least threat to the state. After a vigorous, jazzy Allegro molto, which is quite raucous with heavy doses of brass and percussion, there is a Largo movement of utter seriousness and sadness that features a text by Samuil Galkin about the murder of Jews in Kiev by the Nazis. Galkin, incidentally, spent years in prison for his unSoviet ideas.

Up to this point Weinberg is obviously showing defiance to the Soviets in his choice of poets, but the fifth movement is largely hopeful and peaceful in mood and features a text by genuine Soviet poet, Mikhail Lukonin, who in "Sleep peacefully, oh, people," speaks of a sort of Communist utopia. While the music here has a measure of depth, I believe it comprises the least effective movement in the symphony. Still, this is a fine, if slightly uneven work.

The Rhapsody on Moldavian Themes is a colorful composition for the most part, but has its moments of angst as well. In fact it begins darkly and takes almost five minutes to brighten a bit. The latter half of this thirteen-minute work is quite attractive in its exoticism and folkish vigor. Both pieces on this CD are performed with commitment and accuracy by the St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra, under the knowing baton of Vladimir Lande. The Glinka Choral College Boys' Choir also turn in splendid work. The Naxos sound is powerful and clear. Is this disc worth your attention? If you admire 20th century music or are looking for a substantive alternative to Shostakovich, this release should prove of great interest. Will Weinberg emerge from the shadow of Shostakovich and be regarded as his own man? Hmmm… I can only respond by invoking a similar but much older situation, and ask, will Medtner ever shed his largely uncomfortable association with Rachmaninov?

Copyright © 2012 by Robert Cummings.