The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Gurney Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

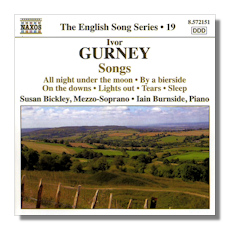

Ivor Gurney

The English Song Series #19

- On the downs

- Ha'nacker Mill

- The Bonny Earl of Murray

- The Cherry Trees

- a Bierside

- Five Elizabethan Songs:

- Orpheus with his lute

- Tears

- Under the greenwood tree

- Sleep

- Spring

- The Apple Orchard (from Seven Sappho songs)

- All night under the moon

- The Latmian Shepherd

- I will go with my father a-ploughing

- Last Hours

- Cathleen Ni Houlihan

- Cradle Song

- The Fiddler of Dooney

- Snow

- The Singer

- Nine of the clock

- Epitaph in Old Mode

- The Ship

- The Scribe

- Fain would I change that note

- An Epitaph

- When Death to either shall come

- Thou didst delight my eyes

- The boat is chafing

- Lights Out

Susan Bickley, mezzo-soprano

Ian Burnside, piano

Naxos 8.572151

Ivor Gurney (1890-1937) is one of a handful of highly original composers in the English pastoral tradition who are either largely misunderstood or – like Havergal Brian certainly and, to some extent, Gerald Finzi – unduly neglected despite having written music of great beauty, originality and insight. Indeed, Gurney's teacher, Stanford, assessed the composer's talents as those of a genius. Scarred by his experiences in the First World War, it's also generally accepted that Gurney (who was also a prolific poet in his own right) had not realized his potential by the time of his premature death.

With Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Holst, Gurney shared a love of the rich and historically resonant West Country – particularly Gloucestershire and the Cotswolds. His songs are infused with this, and with the rhythms and patterns of the vernacular speech of the region's inhabitants. Yet Gurney is successful in blending this love with almost artful (at least to our ears nearly a century later) sophistication in his choice of themes and their expression.

These themes are those to which the Georgian poets and writers were drawn, and which sound so natural to English ears: loss and pain; childhood and memory; the land and our relationship with it; the particularities of our experience of nature: the wind, the night, the moon; and the extent to which anyone (which meant everyone) affected by the slaughter of the War had perhaps somewhat wistfully to adopt a more carefree attitude to life's ups and downs.

Really to perform these 30 short songs (none is longer than four minutes) at all convincingly performers have to be fully in sympathy (or at the very least completely empathize with and understand) the implications of these considerations of idiom. The delivery cannot be histrionic or self-consciously exaggerated. Nor even have a hint at mockery. Nor condescension (Gurney ended his life in a mental hospital). But really enter his world; share his concerns; be taken by his worries and joys. Above all, perhaps, recognize that Gurney's songs evolved from an English tradition that originated in the concentrated world of the Tudor soloist. At the same time performers need to find every note that's modern and respect its own sense in its own right.

Mezzo Susan Bickley and pianist Iain Burnside go a good way towards satisfying such criteria. The pace and togetherness are exemplary. Neither wilting nor lilting, as might happen with a spurious attempt to draw out Gurney's few (and perhaps unconscious?) 'folk' elements. Nor maudlin. Yet nothing too spectacularly idiosyncratic, despite a superficial reaction to the (common, popular) reputation of Gurney. Their partnership, and imaginative interpretation of the meaning of the word, "accompaniment" can be enjoyed throughout: listen to the piano's role in songs such as Cathleen Ni Houlihan [tr.16]. And their collective sensitivity to the Five Elizabethan Songs [tr.s 6-10] and perhaps even more-so in The Apple Orchard [tr.11]. As well as the tenderness of the Cradle Song [tr.17], of whose amazing range of emotion and resolution they really make the most.

At the same time, though, there are occasions when Burnside in particular only narrowly avoids treating such songs as The Fiddler of Dooney [tr.18] as wan miniatures. One of several songs to a text by Yeats, Gurney is not merely "setting" his Irish contemporary's words – but interpreting them. Bickley, too, seems at times to be stopped, "kept out", by the surface of the music, rather than making it completely her own. Technically she is close to faultless with some lovely held high notes and always the right control, which lead to our feeling the greatest confidence in her approach.

But it's as though neither Bickley nor Burnside has really absorbed the idiom, which is a more European (and less romantic) one than those of, say, Ireland or even Finzi. It is possible to let the inner strength and conviction of the ways in which Gurney portrayed his world breathe sufficient life into these works without either rejecting (as passé) or being wholly enveloped by their gentle penetration. For all their exactness and phrasing, the heart of a song like Thou didst delight my eyes [tr.28] is still missing. Almost as if they've been commissioned to perform it on demand. But never really became lost in its depth.

Gurney wrote over 300 songs. Here is a selection that will please many. The acoustic is clean, if a little brilliant, perhaps. The booklet has a commentary on each song and some useful background on Gurney himself. It also has the texts. As a contribution in Naxos' ongoing English Song series the selection is a good and representative one. By the end Bickley and Burnside have created an atmosphere largely faithful to Gurney's creative genius (if Stanford is to be taken literally)… the conviction and subdued passion of Edward Thomas' Lights Out [tr.30], for instance, will stay with the listener long after the CD is returned to its case. But singer and pianist seem never to have completely realized (or maybe nor acknowledged) that they need to show us how they would follow through on an invitation to enter the composer's world.

Copyright © 2009, Mark Sealey