The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

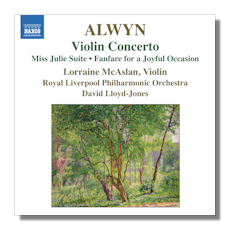

William Alwyn

Orchestral Music

- Violin Concerto (1939)

- Miss Julie Suite (arr. Lane)

- Fanfare for Joyful Occasion (1958)

Lorraine McAslan, violin

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.570705 TT: 58:19

Summary for the Busy Executive: Transformation.

When I think of William Alwyn, I think "prodigy." Not only did he compose, he played flute professionally and painted, translated from the French, and wrote poetry at respectable levels. He became a full professor of composition at the Royal Academy of Music by the age of 21. Obviously, he had mastered the craft. However, his early works, despite their finish, share much with other young composers – mainly, a search for an individual voice. Some of these pieces are even poetic, but they also seem in some way constricted. You sense that something has blocked the composer's real voice from getting out. In many ways, his compositions of the Twenties and Thirties try on masks of other composers. One hears Walton primarily, Moeran, even Vaughan Williams, Elgar, and bits of Delius. In the Forties, he felt that he had found himself and withdrew or destroyed much of his earlier work. Fortunately, he didn't get to all of it, because some of those early pieces, though different from the music we think of as characteristic Alwyn, are quite good on their own. In the late Thirties especially, they give us the sense of the composer's artistic self coming into focus, if not totally defined. The Violin Concerto of 1939 is one of those scores.

Alwyn wrote several concerti: an early piano concerto (1930), the Violin Concerto (1939), the Oboe Concerto (1944), Lyra Angelica for harp (1954), a second piano concerto (1960), and a chamber concerto for flute and 8 winds (1980). My favorite among them is the Piano Concerto #2, which reminds me of the Rachmaninoff concerti in its scope without appropriating that idiom.

Alwyn's only essay in the genre before the Violin Concerto, the Piano Concerto #1 is an odd duck, more Konzertstück than concerto and in one movement. The idiom is more obviously neoclassical – not only Hindemith, but something like Vaughan Williams's Concerto accademico, the British version of Back-to-Bach. Ultimately, it operates on a small, modest scale. Consequently, the Violin Concerto comes as a huge surprise. Three massive chords from the orchestra herald a scintillating annunciatory passage à la Walton, which contains the main motive of a marathon first movement. The violin enters with a Romantic, heroic part, essentially decorating and elaborating the basic idea, a rising and falling scalar fragment with a syncopated hiccup in it. Again, compared to the first piano concerto, the emotional depth astonishes. You have left a relatively safe port for the mighty ocean. Furthermore, Alwyn has begun to find a way to admit high Romantic elements into his 20th-century language, without succumbing to pastiche. It stands but little lower than the Elgar. If not one of the best concerti of all times and places, it's certainly one of the very best produced in Modern Britain. For all the movement's Tchaikovskian length, Alwyn keeps his architecture clear, with a strong first subject group and a lyrical second. The latter shows Alwyn's great melodic gift, not often evident in the music he wrote up to this point. The passionate second movement takes off from Vaughan Williams's pastoralism. We see here that although Alwyn hasn't quite absorbed his influences, he does indeed live up to them. I suspect Vaughan Williams would have been proud to have acknowledged his descendent, had he ever heard the concerto.

Which brings me to a sore point. Alwyn himself never heard the concerto as he wrote it. Henry Wood was to have conducted it, but the BBC, for some reason, rejected the score. The manuscript then disappeared until the Nineties for its first commercial recording. Alwyn had been dead for close to a decade. A run-through with violin and piano took place in a private performance in 1940. Stuff like this happened to Alwyn throughout his career, and with major scores, to boot. He never heard his Second Piano Concerto, either. To this day, the Violin Concerto waits for a full concert performance. What in heaven's name is wrong with the British? I can understand this happening in the United States, where too few people care enough or know enough about classical music to make a difference, but the British actually do care, and furthermore care about their native composers. It's hard for me to imagine a score of such obvious quality going begging to be heard.

The finale begins, not with fireworks, but with a warm, noble tune in the violin over a pizzicato bass. One goes through builds to various climaxes, only to fall back and begin again. The movement as a whole is notable for its lack of virtuoso flash, but in the last minute, Alwyn cannily begins to introduce it, just to prime the audience for thunderous applause. Nevertheless, the movement impresses more as a dialogue between soloist and orchestra than as display.

Outside of Britten, Vaughan Williams, and Adés, England hasn't been all that lucky in its native operas. Vaughan Williams's examples, although he wrote at least two marvelous ones, haven't held the stage, and it's still too early to tell whether Adés will continue the success of The Tempest. Alwyn's Miss Julie, to the composer's own strong libretto based on the Strindberg play, again is too good to ignore, although it has been. Although the BBC aired a broadcast performance in 1977, it received its first stage production twenty years later, again after the composer's death. Even today, despite a superb recording still available (Lyrita 2218), it remains in neglect. Remarkably, the score escapes the British operatic influences of its time, mainly Britten and Tippett. Alwyn's knowledge of the main verismo operatic tradition, his interest in almost every musical strand of his time, and his superb dramatic sense, make this a member of a very small fraternity: a Great British Opera Not by Britten. There are memorable tunes, stunning set pieces, and again a sure dramatic sensibility that makes its points swiftly and economically. The two main influences are Puccini and, believe it or not, Berg, a composer Alwyn honored several times in his late music. Unlike both Britten and Tippett, one doesn't get a dramatic distance through stylization. Like Puccini, Alwyn plunges in to the action fully committed, although unlike Puccini, he has a more sophisticated theater sensibility, necessary for Strindberg. The music is simply too good to lose, and the composer's widow commissioned Philip Lane to extract an orchestral suite from the opera. He uses mainly three scenes: the party in the kitchen where Miss Julie first sees the servant Jean; the love scene; the final tragedy. It's not a bad job, but the opera itself is so much better. I'm not really sure you can excerpt it. For me, the opera is too much of a piece, despite the presence of arias, interludes, and ensembles. Everything works together. I don't envy the job Lane had before him.

Fanfare for a Joyful Occasion for percussion and brass, written for the percussionist James Blades, turned out to be anything but. Blades was to have premiered the work with his two brothers, also percussionists, but fell ill. What should have been an occasion became merely a premiere. The work itself calls to mind similar brass writing by Malcolm Arnold, but the virtuoso percussion writing, particularly a xylophone solo taking up the main theme, takes center stage. This is basically a lollipop. I love lollipops.

Lorraine McAslan, a champion of British music (she's recorded works by Arnell, Benjamin, Bowen, Britten, Clarke, Holst, and Maxwell Davies), gives a strong performance of the concerto, which is no pushover. It requires close attention from both soloist and orchestra, and it gets it from McAslan, David Lloyd-Jones, and the Royal Liverpool Phil. These are no mere run-throughs, but full interpretations. The same goes for the Miss Julie suite and the Fanfare (although I could have done with a bit more juice in the latter). We're lucky the accounts are so good, because we won't likely receive new ones for some time to come.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.