The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

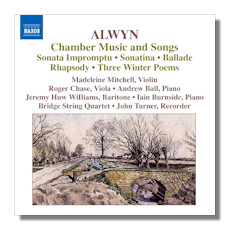

William Alwyn

Chamber Music & Songs

- Rhapsody for Piano Quartet

- Sonata Impromptu for Violin & Viola

- Ballade for Viola & Piano

- 2 Songs for Voice, Violin, & Piano*

- 3 Songs to Words by Trevor Blakemore for Voice & Piano *

- Sonatina for Violin & Piano

- 3 Winter Poems for String Quartet

- Chaconne for Tom for Treble Recorder & Piano *

John Turner, treble recorder

Madeleine Mitchell, violin

Roger Chase, viola

Andrew Ball, piano

Lucy Wilding, cello

Jeremy Huw Williams, baritone

* Iain Burnside, piano

Bridge String Quartet

Naxos 8.570340 TT: 70:15

Summary for the Busy Executive: Alwyn that glisters isn't necessarily gold.

One of those British composers eclipsed by Vaughan Williams, Walton, Britten, Tippett, and Davies, William Alwyn has attracted audiences mainly from recordings. During the Fifties, he briefly had a reputation as a fine symphonist. His symphonies I'd say belong to the Walton wing of British Modernism. I enjoy a lot of his work, often powerful and strongly Romantic, always well-written.

His major works, with the exception of his operas, have received multiple recordings, and now companies are filling in the gaps, bringing especially early work to notice. This CD claims five recording premieres. Alwyn himself more or less repudiated a lot of his early stuff, but in some cases, at least, he was too hard on himself. Nothing on this program can claim the status of neglected masterpiece, but a lot of it charms.

The Rhapsody (1939) for piano quartet begins as an aggressively neo-classical work, but very quickly shows its neo-Romantic heart. The Sonata Impromptu for violin and viola (1940) is a nice, tight work and like most in its genre, aims to fool the ear into hearing more instruments than are actually there. For me the two masterpieces for this ensemble, the Duos of Bohuslav Martinů, show what the Alwyn lacks – some deeper emotional element. Nevertheless, it's a lively, engaging piece. On the other hand, the Ballade for viola and piano (1939) is all moony-swoony emotion, mostly second-hand.

That the songs moved me not at all surprised me. Alwyn's opera Miss Julie, to his own libretto, effectively taps the power of Strindberg's play, and his instrumental music abounds in memorable themes; not so these songs. The songs for voice, violin, and piano (1931) seem stuck in the 1900s, somewhere around Vaughan Williams's House of Life cycle, with tired harmonies. The texts by Alwyn don't make you want to write home about them, but they're good enough for song texts. The pastel, weak-tea Blakemore songs (1940) show a great sensitivity to their texts and fine craft in the interplay between voice and piano, but ultimately I don't care and forget their genteel gestures a couple of minutes after I hear them.

The Violin Sonatina (1933) also seems stuck in the music before World War I, but it moves surely and purposefully. Alwyn doesn't let interest drop. The level of invention remains high throughout within the older idiom, and Alwyn talks to the listener both elegantly and directly. I particularly like the finale, a gigue sandwiching a lyrical middle.

The 3 Winter Poems come from 1948, and here we finally get the mature Alwyn. The superb string writing goes without saying. One feels the desolation and loneliness of winter, the stasis of ice (illustrated by an obsessive repetition of a single motive), and a final dance of snowflakes. One gets a feeling for Alwyn the poet as well as his ease in working out his ideas. The main difference between these miniatures and his string quartets comes down to a lack of sustained, complex argument, but you can tell that both come from the same mind.

Alwyn lived to 80. As he got older, composition took more out of him. The Chaconne for Tom was the second-last thing he wrote and is a tribute and bit of a gag for the birthday of composer Thomas Pitfield. Recorder virtuoso John Turner got Alwyn and his fellow-composers Alan Bush, Gordon Crosse, Anthony Gilbert, and John McCabe to contribute morceau to a presentation volume for Pitfield. Alwyn wanted to beg off, but his wife persuaded him to do it. When he handed it over, Turner noticed that the range didn't fit the treble recorder. Keep in mind this was before the days of music-notation software. Turner meekly asked, since this was to be a facsimile volume, whether Alwyn would please recopy the part for a treble, Alwyn refused and told him to simply use the descant recorder. This was done, but it didn't sound right. Years later, Turner transcribed it for the treble Alwyn meant the piece for.

A chaconne is a repeating harmonic pattern, with or without a repeating bass line (called the ground) over which a set of variations plays. The work begins with a rather torturous ground, which initially sounds all by itself. The recorder comes in with the tune "Happy Birthday," or as near to it as one can get without inviting a lawsuit, and – hard as it may be to believe – the two fit. However, the ground bass drops out early on. The chaconne consists of nine variations and a brief coda, including melodic variations, a canonic variation, a variation in the minor, a variation with "Happy Birthday" in the bass, and so on, until a lickety-split waltz. The recorder and the piano blow a few kisses to the birthday boy, and we're out.

The performers are all first-rate. I single out violinist Madeleine Mitchell and violist Roger Chase for their fine, focused tone. Baritone Jeremy Huw Williams has a Peter Pears quality in his voice, but his diction is much better and he declaims poetry well. The Bridge String Quartet gives an evocative account of the Winter Poems, while John Turner and Iain Burnside realize the sly humor of the Chaconne.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.