The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Korngold Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

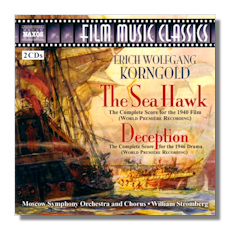

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Complete Film Scores

- The Sea Hawk

- Deception

Irina Ronishevskaya, soprano

Alexander Zagorinsky, cello

Moscow Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/William Stromberg

Naxos 8.570110-11 144:50 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: A landmark film score and a fascinating what-if.

My interest in collecting film music (other than "classical" works like those of Prokofiev and Copland) began in the 1970s with RCA's series of LPs by Charles Gerhardt and the National Philharmonic Orchestra, magnificent in repertoire, interpretation, and sound engineering. I bought almost every one of those LPs (except for those featuring Max Steiner, whom to this day I can't abide). Gerhardt whetted my appetite.

The series also introduced me to Korngold's music, of which I had heard only Heifetz's classic recording of the violin concerto. A violinist friend remarked that it was "pure corn and pure gold." Nevertheless, it ravished me, like a rich dessert. I've since heard a lot of Korngold, including the majority of his operas. Yet the movie music has always held a special place in my listening life, thanks mainly to Gerhardt.

Still, like most albums of movie music, Gerhardt's Korngold consisted of a few cues from any particular film. The cues were wisely chosen (perhaps by the producer, the composer's son George Korngold), but I always longed for a complete score, or at least a soundtrack album. In the meantime, almost the only way to hear the work was to catch somehow the films, and even then, dialogue levels could easily cover the music to the point of inaudibility. Fortunately, with the advent of the CD, more and more film scores have made it to transfer. We have here, apparently for the first time, the "complete" Sea Hawk and Deception. I use the quotes only because the raw cues, in most cases, make for an unsatisfying listening experience, due to their frequent brevity. So arrangers and editors come into the project. John Morgan, a West Coast composer and arranger with a deep knowledge of the history of film scoring, has ministered to Korngold's cue charts with taste and skill.

The Sea Hawk was perhaps the most elaborate and complex of Korngold's movie work. Not only did he write enough sheer stuff for maybe two movies, but the instrumental writing (according to Warner's principal cellist, Eleanor Aller Slatkin) was as intricate as Strauss's Don Juan. Furthermore, Korngold finished composition and recording in a couple of weeks (he had help with orchestration, and fortunately the studio provided copyists, overworked and badly-paid). Some writers claim that Korngold brought the techniques of European concert music to Hollywood films – not strictly true. Dimitri Tiomkin and Franz Waxman in particular had done this before, as had Max Steiner and Robert Russell Bennett in their simpler ways. However, Korngold raised the bar. The full score makes plain the power of Korngold's music in a way that snippets, no matter how individually beautiful, do not. What you get is a score conceived as a whole, like a post-Wagnerian opera, with genuine Leitmotiven and everything. Furthermore, Korngold got the opportunity from director Michael Curtiz to create long musical set-pieces that complemented Curtiz's action set-pieces. What's more, Korngold has constructed a scheme of modulation from one cue to another, as one would do in a symphony or a post-Wagnerian opera, so that you experience even longer spans across several cues. This score, as it swashes and buckles its way through the film, serves as a lesson in film composing, and Korngold's smarter Hollywood contemporaries learned from it.

An altogether different affair and the last movie Korngold scored for Warners, Deception represents a new direction in Korngold's music, less gorgeously sweet and illustrating darker psychological corners without recourse to supernatural fantasy or faux-medieval legend. It concerns the murder of a composer (Claude Raines) by his mistress (Bette Davis), married to the cellist (Paul Henreid) who premières the composer's new concerto. It's as close to film noir as Korngold came, and he felt free to indulge his "modern" tendencies. Most of the cues run very short indeed. Korngold wanted to use well-known classical pieces whenever possible. However, he also composed a piece for the "première" for cello and orchestra, which became his cello concerto. The movie cue is shorter than the final concerto, but only by a couple of minutes, and the final draft strikes more deeply than the cue. Nevertheless, a movie today about (especially!) contemporary classical musicians with this size of budget today runs pretty rare today. The Thirties and Forties audiences seemed more interested in the topic. One thinks of Hangover Square, the Claude Raines Phantom of the Opera, even Citizen Kane for starters, all made within a brief span from each other.

The performances are good enough, like the sound quality. However, the Russian singers wrestling with the English lyrics of The Sea Hawk's vocal set pieces are unintentionally hilarious. Fortunately, the notes provide the text, which turns out to be not that important anyway. The notes, by Korngold maven Brendan G. Carroll (also president of the Korngold Society and the author of the best-received bio of the composer), superbly lay bare the bones and grammar of The Sea Hawk. However, they fall into the trap of telling you more than you wanted to know, particularly about the production of the films. It leads to practically no analysis of Deception. Furthermore, I keep comparing Stromberg's fine reading with Gerhardt's great one, and the RCA sound is sumptuous. I particularly admire Gerhardt's interpretation of the Cello Concerto (I believe he uses the concerto rather than the cue). I would say that the Stromberg recording shows you the sweep of the scores and of course includes more music, but the Gerhardt has not yet become obsolete.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz