The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

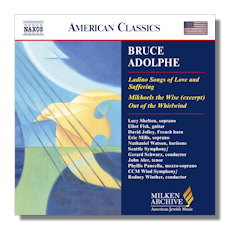

Bruce Adolphe

- Ladino Songs of Love and Suffering 1

- Mikhoels the Wise (Act I, scene 4) 2

- Out of the Whirlwind 3

1 Lucy Shelton, soprano

1 Eliot Fisk, guitar

1 David Jolley, French horn

2 Erie Mills, soprano

2 Nathaniel Watson, baritone

3 John Aler, tenor

3 Phyllis Pancella, mezzo-soprano

2 Seattle Symphony Orchestra/Gerard Schwarz

3 University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music Wind Symphony Orchestra/Rodney Winther

Naxos 8.559413 75:04

Summary for the Busy Executive: This CD probably won't change your life.

I first encountered the music of Bruce Adolphe with a piece for winds, the Night Journey. It seemed to me pretty and imaginative, so I had nothing but good feeling as I prepared to listen to this CD. This time out, Adolphe's music disappointed me.

The Ladino Songs of Love and Suffering take some lyric gems, poetry of Spanish Jews and gives them to the unusual combination of guitar, French horn, and soprano. As an exercise in sonority, it's fairly intriguing, and moreover Adolphe brings it off. The actual musical substance constitutes the main hurdle for me. It's almost entirely what I would consider recitative, no different and no worse than lots of other Modern writing in this vein. But there's nothing truly memorable (other than the instrumental combination) either – nothing that enhances the wonderful poems Adolphe has chosen to set. I don't really expect "Notre Amour," but I'd like something less superfluous than what the composer has given me.

The opera Mikhoels the Wise tells the story of Solomon Mikhoels, the great Soviet Jewish actor (and the father-in-law of the Polish-Russian composer Mieczysław Weinberg [Moisei Vainberg]), undoubtedly the most influential Jewish cultural figure during the Stalin years. Mikhoels was murdered by the secret police during one of the Anti-Semitic purges of Stalin's final years. The scene takes place in a special Siberian enclave set up for Jews by Stalin as the Soviet alternative to Zionism. Most of it consists of a dialogue between Mikhoels and Sin-Cha, a Soviet-Korean woman who has fled her own country to the "protectorate." Sin-Cha wants the visiting Mikhoels to emigrate permanently. Mikhoels gives her all sorts of reasons why he won't – from joking to serious – the most compelling being his conviction that he can do more for Soviet Jewry in Moscow, that the Socialism in which he has put his trust is larger than a small enclave, and that he has no desire to exile himself in his own country. Given the circumstances of Mikhoels' life, the argument becomes ironically poignant. In effect, he heads for an unavoidable tragedy, no matter what action he takes. But the emotion is all in the libretto. The music doesn't stick with you, despite the composer's best intentions. Alone on-stage, Sin-Cha sings a lullaby for Mikhoels and, by implication, European Jewry – obviously a set piece which, by its placement at the end of the scene, should ratchet up the emotional level. Again, the music doesn't deliver.

I liked best the sequence Out of the Whirlwind, settings of Holocaust poetry. Here, the music, rather than the text alone, does the emotional work of moving the listener. However, there's nothing that distinguishes the music from that of fifty other composers. One gets the feeling of a piece well-written, sincerely felt, but not entirely the composer's own.

Adolphe is mostly lucky in his performers. Lucy Shelton in the Ladino songs indulges her annoying habit of singing as if through a mouthful of hot porridge. I often couldn't understand what on earth she was singing about, with translations of the texts in front of me. But this is the only bump in the road. Guitarist Eliot Fisk and David Jolley on the horn lend sensitive support and bring off the tricky instrumental combination, convincing you that it amounts to more than a stunt. John Aler does well as Mikhoels, Erie Mills outstandingly well as Sin-Cha. Both can act with their voices. They give their scene dramatic point. Schwarz and Seattle do what they can with an often dull score (as in timbre, rather than interest, although the sound undoubtedly relates to the interest). The best instrumental work comes from the College-Conservatory of Music Wind Symphony led by Rodney Winther. They get sparks to fly.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz