The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- G. Coates Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

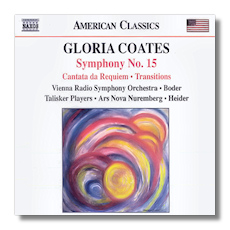

Gloria Coates

- Symphony #15 "Homage to Mozart" 1

- Cantata da Requiem "WW II Poems for Peace" 2

- Transitions 3

1 Wiener Rundfunkorchester/Michael Boder

2 Teri Dunn, soprano

2 Talisker Players Toronto

3 Ars Nova Ensemble/Werner Heider

Naxos 8.559371

American-born, Munich, Germany-based composer Gloria Coates (b. 1938) writes music in an unusual style: she is best known for her imaginative use of slow string glissandos, as well as for chorales that are often sourced in famous works of other composers. She also employs faster glissandos, creating an almost slithering, eerie effect, and often gives her music a sense of constant seething. These descriptions apply most accurately to the newest work here, the Symphony #15, from 2004-05.

Cast in three movements and lasting a little over 22 minutes here, the work has that trademark mysterious quality found in so many large works by Coates. The second movement, subtitled Puzzle Canon, quotes Mozart's final motet, Ave Verum Corpus. Therein lies the connection to Mozart in the work's subtitle; otherwise, there is nothing else here that bears any similarity to that master's music. The Ave Verum Corpus theme, as played here, sounds vaguely like that in Luther's famous Ein' Feste Burg. But Coates quotes it backwards, making it truly a "Puzzle Canon".

The symphony is interesting throughout, both in Coates' use of her trademark wares and other thematic material, as well as in her imaginative orchestration. It isn't a harsh work or at the forefront of avant garde expression by any means, but it isn't conventional either in its lack of catchy or easily recognizable melodies. Her music has been called "Space Age", but it's tougher stuff than that glitzy tag implies and it's also more substantive, especially as heard in the Symphony #15. The performance here, from a live rehearsal on June 16, 2006, is quite convincing on all counts.

The vocal work, Cantata da Requiem, is a relatively early effort, coming from 1972, when it was titled Voices of Women in Wartime. It is quite different in style from the symphony. Scored for viola, cello, piano and percussion, and using various German and English texts that employ descriptions and lamentations about war and loss, it comes across with a dark, tense and dissonant character in the first five of its six numbers. But in the latter half of the last, All These Dyings, the work closes optimistically, with quite lovely, accessible music that reminds me, at least in its mood and sudden shift toward tonality and optimism, to the close of the finale of Bernstein's Symphony #3 (Kaddish). The performance by the Talisker players is excellent and soprano Terri Dunn also turns in fine work, though her voice in the upper regions tends to turn a bit screechy.

The final offering here, Transitions (1984), opens up with howls and other glissando-like effects that more than vaguely recall the river foghorn sounds in Edgar Varese's Ameriques. Again, there is much use of the slow glissando in this three-movement work, though the scoring here, for chamber orchestra, is a bit more subdued. The composer made a larger version of the piece as her Fourth Symphony. The first movement (Illumination) has a mechanical sound in much of the piano writing and percussion effects, though the orchestra tends to be dreamy and mysterious, in contrast. The second movement (Mystical Plosives) is more agitated, with percussion dominated by clacks, eerie piano chords, and tinkling, trilling bells. Glissandos and howls continue here too, as the "transitions" activity moves the music away from seething mystery toward turmoil. The finale (Dream Sequence) halts that advance and turns toward the otherworldly. Glissandos and howls here seem to look toward the heavens, though perhaps in one's dreams. The work is always interesting, though perhaps not as compelling as its companions here. The performances again are excellent.

The notes by Kyle Gann are informative and the sound reproduction in all works is vivid. Recommended to those listeners interested in modern music.

Copyright © 2008, Robert Cummings