The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

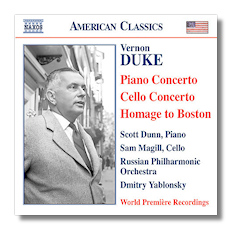

Vernon Duke

Concertos

- Piano Concerto (orch. Scott Dunn)

- Cello Concerto

- Homage to Boston (Suite for Solo Piano)

Scott Dunn, piano

Sam Magill, cello

Russian Philharmonic Orchestra/Dmitry Yablonsky

Naxos 8.559286 57:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: Pleasant.

If Vernon Duke had written nothing more than "I Like the Likes of You," "Autumn in New York," and the score for Cabin in the Sky, he'd still sit permanently in my pantheon. However, he had, in essence, two careers – one on Broadway and in Hollywood, and the other in the concert hall. As a 12-year-old boy with the name Vladimir Alexandrovich Dukelsky, he entered the Kiev Conservatory, where he studied with Reinhold Glière, among others. However, a fellow student and friend – Serge Prokofieff – impressed him more and exerted greater influence on his compositional development.

In 1920, Dukelsky and his family escaped from the Soviet Union (it took the Red Army a while to secure the southern part of the country) and by 1922, ended up in New York by way of Constantinople. Arthur Rubinstein had heard some of Duke's music and asked for a piano concerto "not too cerebral." He got his wish. In 1923-1924, Dukelsky composed one and played a two-piano version which Rubinstein liked and told him to orchestrate. What with one thing and another (including a successful Diaghilev commission), it never got orchestrated, and Rubinstein never played it.

In the meantime, Dukelsky had to make a living and began writing for Broadway revues. Unlike such emigrés as Grosz, Hollaender, and even Weill, Duke mastered the American jazz-based popular song fairly quickly. He seems to have actually listened to jazz before he wrote. Many of his songs actually became jazz standards. Nevertheless, he continued with concert work. For this bifurcated career, George Gershwin (a great admirer) suggested he adopt the name Vernon Duke for his pop stuff and keep his original name for his concert work. This Duke did until 1955, when as a U.S. citizen for nearly twenty years, he dropped "Dukelsky" altogether.

Duke's final years were bitter and sad. In the Sixties, he wrote an article titled "The Deification of Stravinsky" for a fledgling musical journal. In it, he slammed Stravinsky's serial music, especially The Flood and what he considered the blind critical adulation and mostly clueless media hype over anything from the master's pen. Stravinsky and (mainly) Craft fired back a reply written in acid and flame called "A Cure for V.D." in which, I believe, they didn't mention Duke by name once but kept referring to a mediocre composer with compositions like "Oktoberfest in Oswego" and "Mañana in Mexico," about whom Stravinsky and Diaghilev had shared a good, rueful laugh over Diaghilev's "mistake" over his commission for a Dukelsky ballet. As bad as the reply was, the reaction of Duke's fellow musicians was even worse. They wrote angry letters to the journal and cancelled their subscriptions. The journal folded after its second issue.

To me, Duke's essay smacked of disappointment and envy. After all, his works received nowhere near the number of performances as Stravinsky's, and his late music pretty much sank without so much as little bubbles popping on the surface. I don't know if he even composed anything after 1961.

I wish I could report that I found these works neglected masterpieces. After all, it gives me a thrill when I think I've discovered one. These works are well-made and diverting, but little more. Listeners forgot them, not because Stravinsky was a glory hound, but because they weren't strong enough to hang on. The piano concerto, in one continuous go, seems held together with duct tape and spit. When Duke runs out of gas with one idea, he drops it and goes on to something else, without any development that I can hear. You could of course say the same thing about much of Poulenc, but Poulenc has genius themes. Duke doesn't come close. To give a pretty hefty favorable opinion, however, I should say that Gershwin admired one of the lyrical ideas and kept asking Duke to play it at parties. As far as I'm concerned, however, not one theme comes up to anything in Gershwin's own piano concerto. Furthermore, you hear echoes of Prokofiev and Stravinsky without getting either a coalescence into something individual or something as good as the models.

The cello concerto of 1945, written for Piatigorsky, has altogether bigger ambitions. In three formal movements, it nevertheless suffers from the same formal problems as the piano concerto, although to a lesser degree. The best part is formally the simplest: the slow second movement, very beautiful in a quiet way. The finale has arresting moments, although for the life of me I can't recall what they are. Duke has added Gershwin and Shostakovich to his gallery of models – to me, a function of the times, when both composers' works enjoyed booms. Indeed, American publishers, at any rate, were asking composers to write "like Gershwin".

The Homage to Boston, a suite of miniatures for solo piano, runs pleasantly enough, like a new Chevy. However, it really doesn't stay with you all that long. A miniature needs a distinctive idea that, in lieu of intricate development, keeps the listener's interest. I heard this suite five times and forgot it each time. I can't tell you one theme. If I heard it again, I doubt I could tell you what it was or who wrote it.

Still, we don't listen with our entire souls all the time. Now and then, we need something that occasionally prods us for a few seconds before blending comfortably back into the wallpaper. The performances are fine. Dunn's orchestration for the piano concerto seems as good as Duke's for the cello concerto.

By the way, don't take my word for any of this. Check out Robert Cummings' review for a far more favorable opinion than mine.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz