The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Gould Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

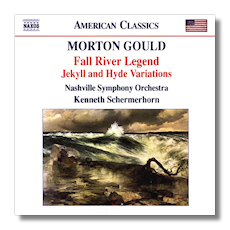

Morton Gould

Rare and Everywhere

- Jekyll and Hyde Variations

- Fall River Legend (complete)

Nashville Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Schermerhorn

Naxos 8.559242 73:48

Summary for the Busy Executive: Pope and populist.

Morton Gould, a composing prodigy, was writing directly into full score by his early teens. He got his first professional job as a musician in his mid-teens. By his early twenties, he was composing and arranging for radio networks. He wrote Broadway shows, scored films, and, in the Fifties, produced and arranged very successful hi-fi "concept" albums. He became that rarest of birds, the professional composer who actually made a living. The radio especially demanded to be fed, and Gould produced shovels-full of light music, all of it above the run of the mill, including classics like the American Symphonettes, American Salute, and the Latin-American Symphonette. Consequently, the fact that Gould also wrote concert works tends to get lost in the general image people have of him. Popular sources drew him: jazz, spirituals, folk music, marches, tap dancing (he wrote two concertos for tap dancer and orchestra), and so on. But, really, he could compose anything in just about any style, as the two scores here amply demonstrate.

The Jekyll and Hyde Variations make a rare appearance. They owe their creation to Dmitri Mitropoulos, then conductor of the New York Philharmonic, who commissioned the piece. People said of Mitropoulos that he wasn't happy unless he could do something for you. What he did for Gould was take him seriously and insist on a work away from Gould's perceived populist, light-classics style. The composer gave him this set of, creepily enough, thirteen variations, written in dodecaphonic, serial – but not atonal – style. If someone hadn't told you, you probably wouldn't have known. Indeed, some of the variations sound almost like modal hymns. The basic theme is not a closed melody, as in Brahms' Haydn Variations, but a "chain" of about seven pieces – strong, memorable gestures, really – which the composer often breaks up and rearranges, like differently colored beads on a string. The theme is also not the tone row, but one built from successive manipulations of the row. Thus, we get music that works closer to the ways traditional music has conditioned us to expect. Despite the title, Gould doesn't try to reproduce Stevenson's narrative. You could speculate why Gould chose the title at all. The liner notes argue that "Jekyll and Hyde" refers to the tonal-atonal split. It's a free country. What's more important, I think, is that the composer gives us not only variations of individual brilliance, but that he has linked them all together to form a dramatic arc. The music becomes increasingly tortured, until the climatic twelfth variation – a symphonic scream – and then a contemplative thirteenth variation, functioning as an epilogue. Incidentally, the variations never really caught on with audiences or critics, so far out of Gould's perceived groove. But they did serve notice that Gould wouldn't be writing any more symphonettes. His late phase incorporated many of the post-war techniques, as well as the enormous influence of Charles Ives, allied to his Stravinskian base. Nevertheless, I consider the work one of his best: a marvelous score that deserves resurrection.

Fall River Legend, a Forties ballet written for Agnes de Mille, has long been recognized as one of Gould's finest works – indeed, from its première. I believe this Naxos release counts as only the second truly complete recording, with the narrator part included. However, the narrator here, James F. Neal, a distinguished jurist, has a cowboy accent you could cut with a chainsaw, and it jars when you consider the Massachusetts locale of the story. The work shows the strong influence of Billy the Kid Copland: lean textures and scoring, clear orchestration, and an idiom based on, but not quoting, folk and popular sources. Gould, like Bernstein, was a musical magpie, taking from many places, but somehow knowing the trick of making his thefts his own. Prokofieff's side-stepping harmonies show up in the ballet's "Waltzes" section, Copland's Billy in the very opening, and Stravinsky in the "Epilogue." All the themes originate with Gould, a superior melodist, but even these echo traditional tunes, even if they don't quote them. For example, the "Hymnal Variations" seem a variation set on an unstated hymn, which I strongly suspect (though can't prove) is "How Firm a Foundation." The entire ballet, incredibly beautiful, keeps your attention. My favorite sequence occurs toward the end: "Church Social," "Hymnal Variations," and "Cotillion," with "Church Social" taking pride of place due to its soaring main theme. Even if you don't know the story, the music follows a strong narrative line, building and relaxing at just the right moments. Gould's dramatic instincts are sure. The actual murders have no music at all, while the "Death Dance" seems to take part behind a scrim of dreams. The most violent music is the "Mob Scene," as the village discovers the bodies, destroys the house, and builds a gallows from the timber. In contradiction to the historical record, Lizzie is found guilty and lynched. De Mille was uncertain about an ending, and Gould told her it would be easier to write gallows music than "acquittal" music. That seemed to settle it. But it does change the meaning of the popular story. Lizzie comes off as less a monster than a victim of slander and mob rule. I've seen productions of the ballet which keep Lizzie's fate undetermined. She steps not off the gallows, but into history. Gould's music works fine for that, too.

The late Kenneth Schermerhorn, long a stalwart on the Nashville classical-music scene (they named a concert hall after him), as a young man played trumpet with the Boston Symphony and studied conducting with Leonard Bernstein. He became music director of the Milwaukee Symphony, American Ballet Theatre, Hong Kong Philharmonic, as well as the Nashville Symphony. He is very much in the Bernstein mold – that is, the young Bernstein. He emphasizes a vital, nervous energy, sometimes at the expense of the whole work. But when he cooks, he's wonderful. The split shows in the performances of Jekyll and Hyde, which occasionally loses its way, and Fall River, which rocks. All that ballet experience paid off, I guess. He does at least as well as Gould himself (a pretty good conductor) on RCA, and you get more music. The ensemble is tight, generally speaking, with the occasional texture that could be clearer, but I nit-pick. Fall River Legend rips and grips. Who would have thought that Nashville, the city built on "three chords and the truth," had such a lively orchestra?

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz