The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Ives Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

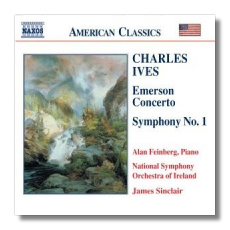

Charles Ives

- Emerson Concerto

- Symphony #1

Alan Feinberg, piano

National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland/James Sinclair

Naxos 8.559175

This release is part of Naxos' ongoing American Classics series. It is an important issue because it divulges the opposite ends of Ives' audacious imagination, coupling a huge, Dvořák-tinged symphony with a work of advanced character the composer never completed – the so-named 'Emerson Concerto', intended to be part of a series Ives called 'Men of Literature'. It was originally conceived as an overture for piano and orchestra devoted to the character and literary persona of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

From drafts made by the composer, musicologist David G. Porter fashioned this work, attaching the tag, 'Emerson Concerto'. It is a bold work – angry, dissonant, dark and dramatic. I'm not sure what it says about Ives' view of Emerson (an irascible, curmudgeonly genius?), but it certainly comes across as a progressive work for its time (circa 1910), and exhibits more of Ives' unique musical persona than it does of Emerson's literary character.

The first movement is restless and stormy, brimming with dissonant power and a craggy, almost Scriabinesque sense of individuality. Not that it contains the mysticism or ethereality of Scriabin – it doesn't, not here or in the succeeding movements. But some of the weird writing calls that composer to mind, especially in the more reflective moments of the second movement. The third movement, though it has its share of stormy music, is perhaps the least turbulent, and the work closes with a finale where the famous motto from the Beethoven Fifth Symphony – heard throughout the work in various guises – presents itself most clearly and ominously: Try the eerie ending, where that motif sounds utterly sinister. An interesting, if flawed composition then, with the outer movements containing the most compelling music. Alan Feinberg gives a thoroughly compelling performance and is abetted by the incisive leadership of James Sinclair, who draws fine playing from the Dublin-based orchestra.

The Symphony #1 is a well-crafted four-movement effort which Ives used for his graduation exercise at Yale University, where he studied under the meddling and unimaginative, though thoroughly-trained, Horatio Parker. The work is fairly light and attractive, though its forty-five minute length may not be justified. The Dvořák influence is undeniable, especially in the second movement, which is clearly modeled on its counterpart in The 'New World' Symphony, then a sensation in America and Europe. Again, Sinclair and his forces turn in fine, spirited work. The sound in both pieces is vivid, and Jan Swafford's notes are illuminating.

Copyright © 2003, Robert Cummings