The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Daugherty Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

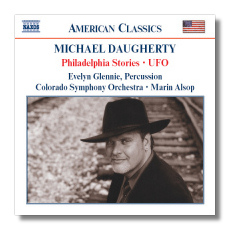

Michael Daugherty

- Philadelphia Stories (2001)

- UFO (1999) *

* Evelyn Glennie, percussion

Colorado Symphony Orchestra/Marin Alsop

Naxos 8.559165 64:38

Summary for the Busy Executive: High and low.

Michael Daugherty's music confuses many who think about it. They tend to mistake him for a light, in the sense of minor or trivial, composer. By me, he's an American poet, really no more light than Whitman or Ives. I admit his eccentricity. He combines within himself the hipster and the teen cruisin' for burgers on a Saturday night. As a teen, he began playing in school marching bands and in rock bands. He played jazz professionally for a while. However, he also studied at North Texas (a cradle for avant-garde musicians) and Yale and in New York with serialist Charles Wuorinen, where he met Boulez. He spent some time at Boulez's IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique) in Paris, and produced music by Conlon Nancarrow and Gyögy Ligeti. He has serious avant-garde street cred. Why doesn't he sound serious and Angst-ridden?

While knocking about Europe, he also studied with Ligeti, who encouraged him to incorporate American vernacular music, including jazz and rock, into his concert music. Most American composers with a pop background tend to keep it separate from Hochkultur. In short, Ligeti encouraged his student to get his entire self into music.

Daugherty took this to heart. He recognized the mutt culture of the U.S. and acknowledged the strength of his attraction to it. Part of an artist's gift is noticing the extraordinary in the normal, effectively unnoticed thing. If the sight of a '59 Caddy with tailfins does not excite you as much as a Brancusi, Daugherty may not be your composer. On the other hand, a musician of enormous cultural breadth works to adapt that culture to contemporary composition techniques. Daugherty also writes pieces inspired by Modern art.

Daugherty describes Philadelphia Stories as his third symphony. Its genre matters less than its music, of course, and he's entitled to his wrong opinion. By me, this is no symphony, or even a cohesive composition, shown by the fact that the first movement, "Sundown on South Street," and the last, "Bells for Stokowski," are often programmed on their own. The score resembles more an Ivesian set, independent pieces tied together by an extramusical concept – in this case, Philadelphia. Daugherty seldom gives you classical forms. He seems happiest as a tone poet, and I think this gives audiences another in with the music. "Sundown on South Street" captures big-city energy, as Daugherty leads us on a tour along the street of the nighttime musical joints. A great variety of pop music styles passes before us. The slow movement, "The Tell-Tale Harp," seems the weakest. It depicts the city once the sidewalks have been rolled up for the night. Edgar Allen Poe wrote his horror classic "The Tell-Tale Heart" in Philadelphia, although that's a truly slender thread to tie this movement to the others. Daugherty's movement features two harps, placed stereophonically on each side of the stage, spatial shaping of sound one of the composer's favorite effects. It combines moods of walking through a graveyard, lush nocturne, and scherzo excitement (7/8 time). However, it doesn't seem as sharply focused in conception as its companion movements. "Bells for Stokowski" meditates on the public career of conductor Leopold Stokowski, the creator of the Philadelphia Orchestra's "Philadelphia sound." We hear, among other things, Russian-like themes bringing to mind Stokowski's treatment of composers like Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky, a passage reminiscent of the C-major prelude from Book I of Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, which brings to mind Stokowski's classic, super-glam arrangements of Bach keyboard pieces, and moments of hard-edged Modernism, recalling Stokowski's pioneering performances of then-Contemporary music like Schoenberg, Mahler, Stravinsky, Berg, Webern, and, later, Ives. Furthermore, Daugherty alters the orchestral sound in a way that suggests Stokowski's experiments in orchestral seating, butt within the standard orchestral seating arrangement, accomplishing this by playing on ambiguous timbres of various instruments – violas sounding like violins and cellos, for example, or horn sounding like an oboe. At the finish, we hear organ-like buildups of sound, register upon register (Stokie began as an organist). A very evocative piece and, it turns out, a Daugherty "hit" on its own.

UFO, a virtuoso piece for percussion soloist and orchestra, explores the poetry of the tabloid staple of strange flying craft piloted by the green and be-tentacled. The conceit allows Daugherty to indulge in hardcore avant-garde timbral effects. Here, we see Daugherty's Darmstadt background most in evidence. Five movements make up the work: "Traveling Music," "Unidentified," "Flying," "???," and "Objects." It offers little narrative, and its two most common moods are the exhilaration of flying through the vastness of space and the strangeness of close encounters.

Evelyn Glennie gives a jaw-dropping performance in UFO. Her hands move quicker than the eye and almost the ear. However, she also can play very lyrically. Some of the effects Daugherty specifies can sound merely bizarre in other players. She makes them beautiful, without sacrificing their alien distance. Incidentally, her album photo makes her look a bit alien herself. She resembles a wild animal caught in a camera flash. This isn't a nice thing to do to such a lovely woman. Marin Alsop "gets" Daugherty and the Romanticism hiding beneath his ironies and jokes. She keeps a convincing narrative going in "Bells for Stokowski," which can sprawl and natter in other hands. The Colorado Symphony plays with conviction. I complain only about the recording of "Tell-Tale Harp," where the stereophonic image insufficiently separates the two harps, which should be antipodal. Here, the first harp is clearly on audience left, while the second sounds somewhere to the near right of the conductor's podium. Other than that, a fine disc.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.