The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Flagello Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

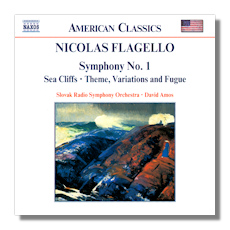

Nicolas Flagello

Symphony #1

- Symphony #1

- Sea Cliffs

- The Piper of Hamelin - Intermezzo

- Theme, Variations and Fugue

Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra/David Amos

Naxos American Classics 8.559148 63:49

Who carries the banner of Romanticism in the mid-20th century? Who is the successor of Rachmaninoff and Puccini? I refer to true romanticism – music that is rooted in the 19th century in both gesture and content – that proudly uses the standard orchestra, the tonal system, and all the sonata and variation forms, but just as importantly has freshness, personality and life, and judiciously "steps out" in more modern rhythmic, contrapuntal and harmonic complexity, when called for. I do not seek the "neo"-romantic who strives for a primarily emotional pay-off but uses all manner of non-tonal, non-structured, even ethnic idioms as may suit him (yes… I'm in that class as a composer, but that is not the current subject) or what I might call the "retro-romantic" who reverts to oversimplified "pretty" kid-stuff (out of gentlemanliness – I refrain from naming names… )

If there is true late-romantic writing after 1950, perhaps that precarious distinction belongs to Nicolas Flagello (1928-1994). Here is true heart-on-sleeve emotional music, throbbing and crying out, in a personalized tonal and formally traditional language. Some works actually SOUND like Rachmaninoff, though they do so naturally, comfortably and warmly. In the later and darker works, the involvement and structure and counterpoint bring about a density which is more clearly modern. Very few composers seek climaxes of Flagello's intensity; his writing is a virtual textbook on achieving them. For example, there is the moment where a steady crescendo appears to have nowhere to go, and the composer suddenly drops back to mezzo-piano, with an agogic hesitation and concurrent interesting harmonic turn – only to build again even further than before. This technique is hardly unique to Flagello, but he uses it both very frequently and with great skill.

The earliest work presented is Theme, Variations and Fugue. Flagello was not yet out of his 20s and had completed study and degrees under the tutelage of Vittorio Giannini in New York and a year of "European polishing" under Ildebrando Pizzetti. To these ears the piece is a student work – albeit one of great promise. The pitfall the modern composer faces in this form is easily expressed if not as easily surmounted. Can the listener identify exactly where the "double bars" are – as one variation ends and a new one begins, and does the listener find that the first four bars of a variation all but pre-figure the rest of that section? In the 18th century such sectional dryness may have been acceptable – but it was not so earlier for Luis Milan or Henry Purcell, and a modern work like Peter Mennin's Symphony #7 clearly succeeds in this regard. The Flagello work does not generally do so despite some fine moments, here tender and here exciting. I find the work further flawed by a theme which is a little too tonal – starting by spelling out 5-3-1-6 of a minor key; the opening arpeggio becomes tiresome. The ending uses blazing brass triads with chiming percussion and while quite effective it seems to come somewhat "out of nowhere".

About a year later Flagello wrote Sea Cliffs, which is a melodious, sentimental, short work for string orchestra. While there is a resemblance to "The Impossible Dream", Flagello is certainly blameless. Man of La Mancha was not yet written.

The "main event" of this CD is Symphony #1 written in the middle and late 1960s. As it turned out, this was the composer's only official symphony for full orchestra; #2 turned out to be for wind ensemble. The earlier "Missa Sinfonica" (Flagello actually used this title- mixing Latin and Italian, where "Messa… might have been more consistent) is something of an orchestral analogue of the mass ordinary, and despite its length and scope he did not give it a symphonic number.

According to the booklet notes, the structural inspiration for the Symphony was the Brahms 4th. I must say that I find this comment tangential and indeed distracting. Indeed, the above-mentioned 5-3-1-6 opening of the earlier work exactly matches the pitches that open the Brahms 4th – but in Symphony #1 both idiom and atmosphere suggest other ancestry. Flagello's work opens with a sonata form, but the "A" and "B" themes are melodically similar, which, of course, is a strange fingerprint of Franz Joseph Haydn's.

More deeply, in mature Flagello, just what IS the sound of the music? What is Romantic about it; what is personal; what is modern? I believe there is a clear answer to this in a trait which is shared by others, but a true major fingerprint for him. Melodic statements often begin boldly but clearly – pitches and rhythms one can remember or indeed sing – for the first phrase. However, then, where an answering second phrase should be – we find a headlong, careening rush – wider range – scrambling rhythms, volcanic scoring. We may lose our ability to recall the tunes – we may be irritated by what sounds like gesturing – but at its best, this method achieves an edge-of-the-chair feeling of desperation and even panic. Although the music may be "sostenuto", "bow-on-the-string", these precipitous ideas often end in extremely short staccato (or detaché/martellato) moments, reinforced with side drum or suspended cymbal punctuations.

On repeated listening to the first movement of the symphony, I could not resist a comparison which may seem strange. In this to-the-abyss rushing complexity, I think there is one clear predecessor – the first movement of the Tchaikovsky 4th symphony. In its 9/8 meter – with frequent melodic bravura, and rhythmic/orchestral attacks, it is unique in Tchaikovsky's genre, where usually the melodies keep the "lid on" no matter how impassioned or tragic the thinking may be.

Now I will make a stronger statement. I am not suggesting that Flagello is operating in the shadow of Tchaikovsky, but rather that – first movements at least – Flagello in Symphony #1 SUCCEEDED in writing the composition Tchaikovsky was TRYING to write in Symphony #4.

As expected, Flagello provides a whopping climax – propelled by an irregular rhythmic "motor" using the pianoforte, at 5:42 of the first movement. There is an after-shock to end the development and introduce recapitulation at 6:20, on a bona-fide dominant-tonic cadence. This may show us that Flagello's heart is still in tonality; I personality find it disappointing, but we can chalk that up as my modality-prejudice.

The slow movement has several brooding solos, but that hardly prevents equally climactic writing and rhythmic/contrapuntal roaming. The scherzo finally gives us a very periodic melody, which is repeated many times. It is, however, the kind of music that gets under one's skin, and has some daemonic character, so the reiterations please us in spite of ourselves. The harmonization is usually dissonant but rhythmically regular and obsessive. Near the end, he again shows us the whole bag of climactic apparatus, driving rhythms in the orchestra with four unison horns on fortissimo melody; a display of blazing triadic consonances with bells going off and – finally, when he appears "out of gas", a bone-chilling cluster-tight dissonance for strings, set off with a side drum four-note flam.

All this sets the stage for a big finale, and Flagello offers a showcase of variation technique. He begins "a la chaconne", then branches off into more traditional variants, and finally presents a fugue, with an epiphany-like conclusion. Of course, the listener is tempted to evaluate the movement not only for its position in the symphony, but as against the early variation work presented here and discussed above. The theme is more opaque, Flagello's control of orchestra and structure are fully developed. The content is rich emotionally; the form is thorough and mature. However, I must confess that to my ear form and content are not working hand-in-hand. I do not feel one enforces the other. Rather I find myself (and I presume Flagello himself) lost in the labyrinth of his own construction. This does not prevent us from enjoying some very thought-provoking and at times cathartic music, and if the finale is not thoroughly equal to the task, the symphony as a whole is a major success.

Shortly after the symphony, Flagello wrote an opera on The Piper of Hamelin, the intermezzo of which is presented here. Certain emotional shifts seem less than satisfying, but I feel it is wiser to reserve judgment until one hears the entire work – which is, apparently, available these days on CD.

By now collectors are well aware that recordings such as this one are often made by orchestras who have never seen or heard the works before – and likely never will again. 20 minutes of music are recorded in three hours time – and then the editing techniques come into play. This is often accomplished with European orchestras who are economical to use and technically excellent. Some middle-ground American orchestras have participated – Nashville on the Naxos series, and Altoona and Owensboro in a recent CD of compositions of my own. This may sometimes provide the possibility that a concert performance may be scheduled, which, in my opinion, does a lot to personalize the parts for the orchestral personnel.

So, in these foreign-orchestral under-pressure recordings, are there moments where one feels a player – most often a solo woodwind – is playing a major solo and simply does not know that he is? Are there moments where the high string intonation gets a bit rough? Yes – of course – but the Slovak orchestra under David Amos's experienced and impassioned direction keeps any such flaws to a minimum and generally delivers richly emotional and convincing renditions of these works.

Copyright © 2003, Arnold Rosner