The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- M. Gould Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

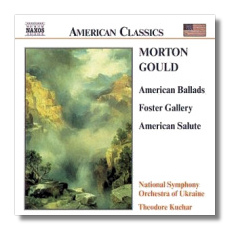

Morton Gould

Americana

- American Ballads

- Foster Gallery

- American Salute

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine/Theodor Kuchar

Naxos American Classics Series 8.559005 73:48

Summary for the Busy Executive: All that doo-dahs is not doo.

As a conductor and a commercial musician, Morton Gould made a lovely dollar. However, beyond perhaps three works, hardly anyone knows him as a serious composer. To some extent, this lack of recognition stems from his feud with Leonard Bernstein, who belittled Gould's music every chance he got and effectively denied Gould a regular New York venue. This, according to the Peyser Bernstein bio (so I have no idea whether it's true), culminated in a shouting match between the two where Bernstein ticked off all the "cribs" in a Gould score, ending up with "and BERNSTEIN!" Of course, if you're going to count steals, Bernstein has more than his share, and it turns out that Gould had written the score in question before Bernstein had graduated from Harvard. Even so, Bernstein made an elementary mistake: that cribbing necessarily means unoriginal. One sees this in Bernstein's own music, where Hindemith, Copland, Stravinsky, Blitzstein, Foss, Poulenc, and God knows who else hap pily remix to form an idiom called Bernstein. Gould steals far less obviously and speaks with just as individual an accent. Beyond this problem, however, the swing to the International School of the Fifties through the Seventies didn't help Gould, just as it didn't help Bernstein himself, or Copland and Barber for that matter. Most of the recordings of Gould's major works, like those of Bernstein's, came from a conductor who was also the composer. With the death of both men, one can get some independent verification on the lasting power of their music. Even before he died, other conductors had begun to take up Bernstein's music. The same thing has started to happen with Gould. This is the second Naxos CD devoted entirely to Gould's music.

Somewhere around the age of nineteen, Gould began professional employment as a staff composer to the large radio networks, at a time when both NBC and CBS kept not only symphonic orchestras, but "pops" and dance orchestras as well. He eventually worked for NBC, CBS, and Mutual. He had going for him not only his ear and his talent, but also speed. Deadlines in the radio business were constant and almost always short. He quickly got into the habit of composing directly onto full score. He also wrote music that "art" composers seldom have to deal with: little "pops" pieces, program "stings," and so on. Compared to someone like Copland or Sessions, Gould has a huge output of light music. Nevertheless, Gould lite has more to say than many other composers' "full." The Prokofieff of, say, The Love for Three Oranges "March" often serves as the model here, although Gould's music speaks in a solidly American, even jazzy, accent. Most of the works on the program com e from the lighter part of the spectrum. All of them mine national songs and folk hymns for thematic material. Gould wrote these kind of works a lot, much as Vaughan Williams did, all throughout his career. Despite the fact, however, that you will find not one original basic musical idea among these three scores, all of them show a brilliant, strongly individual composer pretty much near the top of his game.

Foster Gallery, the earliest item on the program, as you might guess riffs on the melodies of Stephen Foster. I admit up front I don't care for Foster's songs and much prefer those of his contemporary Henry Clay Work, whom I consider the superior melodist. At any rate, the score has much in common with something like Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition - a suite of, in effect, character pieces. We find movements based on such gems as "Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair," "Nelly Bly," "Old Black Joe," "Old Folks at Home" ("Swanee River"), and so on, but these are not arrangements so much as re-compositions. Gould tears down the Foster tunes to their constituent molecules and recombines these molecules to form structures that are instrumental fantasias, rather than songs, pretty similar to how Vaughan Williams sets to work on his Tallis Fantasia or Five Variants on "Dives and Lazarus". "Camptown Races" not only opens the work (parts of it close the piece as well, alternating with bits of "Oh Susanna"), but in variation it also functions as a "link" between movements, again like Mussorgsky's Pictures ' "Promenade." The other movements are pretty much sui generis in their treatment of the Foster tunes. "Canebrake Jig" makes use of the song "Some Folks" and really isn't a jig at all, since it dances in resolutely duple time. "Old Dog Tray" serves as an introduction to the finale, based on "Oh Susanna" and "Camptown Races" trading licks with one another. The same thing happens much more quietly and in a much more integrated manner in the sixth movement, based on "Old Black Joe" and "My Old Kentucky Home." As far as the rhetoric of the movement goes, the two tunes "interpenetrate."

The orchestration will make your jaw drop. My favorite is one of the "Camptown Variations," for a solo quintet of flute, trumpet, trombone, violin, and banjo. Eat your heart out, Richard Strauss!

The idea of tearing down and re-combining previous material carries over into the other works on the CD, but with very different effects. American Salute probably counts as Gould's most recorded piece (it serves to this day as a hi-fi "demo," which gives you some idea of how yummy the orchestration is), Although I think it respectable, I find it a good job, rather than totally satisfying (Gould not only wrote it in a single night, he revised it in the same night). The orchestration dazzles and in that lies the work's chief appeal to me. The piece is both a straightforward variations set on the Civil War hit "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" as well as a quick-march.

Written for the U.S. Bicentennial, American Ballads is by far the finest and most intricate piece here. The work has six substantial movements (as opposed to the equally-long Foster Gallery's thirteen): "Star-Spangled Overture" (based on "The Star-Spangled Banner"), "Amber Waves" ("America the Beautiful"), "Jubilo" ("The Year of Jubilo"), "Memorials" ("Taps"), "Saratoga Quickstep" ("The Girl I Left Behind Me"), and "Hymnal" ("We Shall Overcome"). The titles provide the clue that these aren't "arrangements." They are original compositions, significant and complex in their own right, with far more intervention and reshaping than in, say, Stravinsky's "Pergolesi" Pulcinella. Each I think a masterpiece and the work as a whole in many ways a reinterpretation of the Folk-Populist movement in American music of the Thirties and Forties. Most American composers had moved on in the Fifties, including Gould, who, like Elliott Carter and others, became fascinated with the simultaneities of Charles Ives. American Ballads thus becomes a re-engagement with older, more politically- and culturally-naïve ideas. I find a nostalgia, a sense of loss and mourning in much of the piece, particularly in the sobering, Ivesian "Memorials" movement, a tribute to the country's "honored dead." Remember that this work appeared shortly after Watergate and the Viet Nam War. Gould, usually considered at best an entertainer rather than an artist (you won't find him mentioned in most scholarship on Modern American concert music), violates expectations to a great extent. And yet American Ballads remains essentially optimistic, though not brainlessly so. Hope remains alive, if not exactly triumphant, in the "Hymnal" movement on "We Shall Overcome" - surely no accident that Gould made this the finale. Gould supported black civil rights long before it became fashionable. In short, I see the entire piece as a tract for the times.

Kuchar and his Ukrainians (and, man, doesn't that sound strange?) do a wonderful job with these works. I reviewed Kenneth Klein and the London Philharmonic on Albany TROY202, a full-price disc which I enjoyed more for the program than for the performances (it contains American Salute, Spirituals for Strings, and American Symphonette #2 as well as American Ballads). The London Phil do a thoroughly professional job, but the Ukrainians play with far more fire and understanding. The notion that only Americans can play American music makes as much sense as the assertion that only the Viennese can play Mahler. Our national music does indeed travel. Add to this superb sound and the budget price, and the Naxos seems to me the better buy.

Copyright © 2006, Steve Schwartz