The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Alwyn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

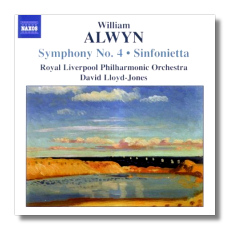

William Alwyn

- Symphony #4 (1959)

- Sinfonietta for String Orchestra

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.557649

Summary for the Busy Executive: A good job, but not as extraordinary as other entries in the series.

Alwyn's fourth symphony was the last of a planned cycle. Apparently, four different solutions to symphonic writing came to him at one go, and this inspired him to embark on the multi-work project. He also wrote a fifth symphony, inspired by Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, but it came much later and connects to the others weakly, if at all. One idea, which the composer referred to as a "motto" (although it tends to appear anywhere in a particular movement), runs through the set, further binding all four together.

Alwyn sings in a big, neo-Romantic way, sort of an off-shoot of the Walton First. His symphonies have the richness of a Dickens novel, a Shakespearean prodigality of invention given shape by a master of thematic manipulation. The bag of basic themes is small – essentially three for the entire fourth symphony, although the composer himself speaks of two groups of three pitches each. However, the composer's brilliance in varying them gives the illusion of more entropy than the actual case. Nevertheless, this kind of microscopic attention to detail and the deliberately limited thematic resource in hindsight points to the composer's later brief adaptation of dodecaphonic serialism (essentially confined to one incredible work, the string trio from the Sixties). The orchestral sounds are varied and, in general, sumptuous. The fourth symphony constitutes no exception, and indeed the impression of a thematic flood probably makes itself felt even more strongly than in the other three. In my opinion, it's also the most unconventional formally, with an opening allegro, a scherzo (probably the weightiest movement), and a slow finale, all around ten minutes long.

In contrast to, say, the typical Mozart or Beethoven counterpart, the first movement does not present a rhetorically cohesive structure. Indeed, the mood changes so many times, the argument risks falling apart entirely. As far as the "eye" goes, all is fine: the "tunes" all share a family resemblance. The ear, however, has to do a lot of work. It reminds me of a family dinner where each member talks about his particular day, without much of an attempt to relate to the stories of others. There's very little in the way of conventional transition. Changes are either short or downright abrupt, mostly pivoting on a kind of rhythmic punning. A three-note dotted rhythm suddenly becomes a syncopated six-note rhythm, although you can tell how he moves from one to the other. At times, this kind of shift reminded me of the classic spoonerism, "The shore was strewn with erotic blacks."

The second movement, a barbaric scherzo enclosing a worrisome trio, may bring to mind Holst, in particular the Fugal Overture (scherzo) and The Planets' "Saturn" (trio). What I've come to regard as the symphonic cycle's "motto-rhythm" pounds out prominently in the scherzo. All sorts of contrapuntal tricks pop up (including the scherzo subject played against itself upside-down, in canon, and every which way but loose), and one encounters brilliant orchestral touches, including a marvelous passage for violin solo in chords at the scherzo subject's return.

The slow finale updates the Mahler adagio, and here and there one finds a Mahler turn of phrase and passages of Mahler-inspired counterpoint within Alwyn's own classic modern idiom. As the movement progresses, we recollect, not necessarily in tranquility, the earlier movements, which the adagio gently pushes away, and we end in a Mahler-like "long farewell."

The Sinfonietta for String Orchestra counts as a "late" Alwyn orchestral work, since toward the end of his career, he concentrated on opera, vocal music, and chamber pieces. It followed by a few years the string trio and, although resoundingly tonal, still shows traces of Alwyn's study of the Second Viennese School. Indeed, it combines in idiosyncratic ways fin de siècle Viennese thematic shapes, especially in the slow, lyric passages, with English neo-classical rhythms and harmonies. Why he called it a Sinfonietta rather than a Symphony, I don't know, unless he worried about a length of "merely" twenty-two minutes. However, to me, it's as much a symphony as Honegger's Second, also for strings, and matches that score's vigor as well. The breeze from the land of Angst mit Schlag may have something to do with Alwyn's desire to write a work dedicated to the eminent musicologist and analyst Mosco Carner, who championed the Schoenberg school, as well as Bartók and Bloch, among others. The composer confessed that he had "centred" the work (whatever that means) on a quote from Berg's Lulu, an opera he admired. The particular phrase "haunted" him. The Sinfonietta – in three movements, fast-slow-fast – proceeds a little more conventionally than any of the symphonies. One looks in vain for the quick changes of mood found in the fourth, for example. Things here are much more of a piece. One finds the usual contrast of "masculine" and "feminine" themes, rather than the bounteous variety of shades in the symphonies. The Viennese notes tend to sound more noticeably in the lyrical sections, and, accordingly, they achieve greatest prominence in the slow movement, which I would describe as a dodecaphonic adagio without the dodecaphony. It reminds me of Schoenberg before he tried to bury tonality, when (like Wagner in Tristan) he reveled in soars and swoops of major sevenths and minor ninths. Alwyn, however, writes more cleanly than Schoenberg. In fact, the string writing throughout the Sinfonietta shows a mastery of texture and technique. Alwyn, by the way, was a flutist. After a foot-stomping opening, the third movement settles into a variation set, which includes an intricate fugue. Here, we have the some of the mood-shifting that so strongly marks the symphonies, but the sturdy formal and rhetorical clarity takes a bit of the edge off. The work ends quietly, on a prolonged sigh.

I believe this marks the end of the Naxos/Lloyd-Jones symphonic cycle, although I read that there's more Alwyn on the way. At least, I hope that's true. Overall a splendid series, it competed easily with the composer on Lyrita and Richard Hickox on Chandos. I confess, however, to slight disappointment with this particular disc, mainly because of the first movement of the Fourth. Like the Brahms Fourth or the Sibelius First, it needs a very capable conductor indeed (and apparently a bit of luck) to keep the thing from disintegrating like an aspirin tablet in water. Alwyn certainly gives you very little help. Lloyd-Jones has proven himself again and again as a fine conductor, but I think Hickox does a better job here of holding things together. But that may not count for much. Lloyd-Jones does well enough, the engineering is outstanding, and you really can't beat the Naxos price.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz