The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Shostakovich Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

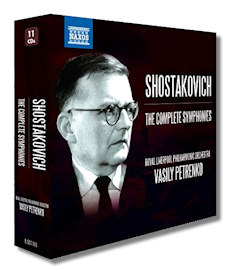

Dmitri Shostakovich

Complete Symphonies

- Symphony #1 in F minor, Op. 10

- Symphony #2 in B Major "To October", Op. 14 2

- Symphony #3 in E Flat Major "The First of May", Op. 20 2

- Symphony #4 in C minor, Op. 43

- Symphony #5 in D minor, Op. 47

- Symphony #6 in B minor, Op. 54

- Symphony #7 in C Major "Leningrad", Op. 60

- Symphony #8 in C minor, Op. 65

- Symphony #9 in E Flat Major, Op. 70

- Symphony #10 in E minor, Op. 93

- Symphony #11 in G minor "The Year 1905", Op. 103

- Symphony #12 in D minor "The Year 1917", Op. 112

- Symphony #13 in B Flat minor "Babi Yar", Op. 113 2

- Symphony #14, Op. 135 1

- Symphony #15 in A Major, Op. 141

1 Gal James, soprano

1 Alexander Vinogradov, bass

2 Huddersfield Choral Society

2 Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko

Naxos 8.501111 11CDs

Although its name is that of a provincial orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (RLPO) is actually the UK's longest-surviving professional orchestra. The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society was founded in the early nineteenth century and also manages the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir and the Liverpool Philharmonic Youth Orchestra. The only professional orchestra in the UK to have its own dedicated hall – the art deco Liverpool Philharmonic Hall – the RLPO played an important part when Liverpool was the European Capital of Culture in 2008. Conductors and performers who have distinguished themselves in Liverpool include Furtwängler, Szell, Monteux, Koussevitzky, Walter, Casals, John McCormack, Elisabeth Schumann, Menuhin, Solomon, Moiseiwitsch, and Maggie Teyte. Both Sir Henry Wood and Sir Thomas Beecham are closely associated with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, whose "principal", now "chief", conductor since 2006 has been Vasily Petrenko, who was born in Leningrad in 1976 and made his conducting debut with the RLPO two years earlier.

The Orchestra's suitability to tackle the mammoth cycle of Shostakovich's 15 great symphonies is evident from the very first bar of their performance of the First Symphony. All 15 symphonies by Shostakovich (1906-1975) have just been made available as a set of 11 CDs on Naxos; they were first released singly as they were recorded between April 2008 (the Eleventh) and September 2013 (the Thirteenth). It's a superb set which has garnered multiple accolades and can be safely recommended in every respect.

The first quality which many listeners will probably notice is precision. The trills, drum rolls, brass and strings in the higher registers – all hallmarks of Shostakovich's quasi-"military" moods – are played with exactness and transparency. But never soullessly. Indeed, in the early Second and Third Symphonies (all date from between 1925/25 and 1929), there is the passion, if not yet the "sear" which first emerged in the Fourth, so typical of a Shostakovich influenced (most notably in the Fifth) by the high Romanticism of Mahler. The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir doesn't let the idea of declamation overrule their sense of the need for clean articulation and perhaps a bit of ironic restraint in both the third movement of the Second, "To October" [CD.2 tr.3] and the sixth movement of the Third, "The First of May" [CD.1 tr.10]. Early works these first three symphonies may be, but Petrenko has no doubt about the huge amount of musical substance which they contain. Dynamic is rigorously observed – as is typical throughout the entire cycle. The Second begins very quietly [CD.2 tr.1], very slowly; while the Third arches across a series of emotions beneath the apparently extrovert surface.

Indeed, Petrenko is particularly adept at probing beneath the surface. It's been said that the Symphonies were the "public" Shostakovich to the "private" figure (or at least his internal or even semi-concealed world) of the String Quartet cycle – which also numbers 15 works, of course. This skill of interpretative penetration by these performers emerges in the Fourth Symphony [CD.3], where, for the first time, the composer allows his understanding of orchestral color to paint the rich and varied picture which we associate with Shostakovich the symphonist. There are lengthy passages of xylophone and strings in staccato marches, flute and woodwind dancing above divided strings, cymbals and timpani to introduce – not summarise – passages, unexpected crescendi, diminuendi and abrupt "about turns" in dynamic, rubato, and even "crude" refrains redolent of Mahler's inclusion of folk and street music acknowledging other trends of the 1930s. Above all, there is a muscular reflection on the strange interaction between poignancy and the composer's well-digested sense of the horrors in the world in that period. Although the continuity which distinguishes this cycle is helped, maybe even underpinned, by use of the Leitmotiv, especially DSCH (D, E flat, C, B in German notation) and EAEDA (for Elmira Nazirova, a student of the composer, with whom he fell in love), Petrenko's understanding of the music plays as much of a part in achieving the sense of purposeful structure as the mechanical.

In the Fifth, too, the music is approached as music, not documentary. This best known of Shostakovich's symphonies is played in the same spirit as the Fourth: the tension never lets up; yet the longer first and third movements (twice as long in the Fourth as the Fifth) develop in their own time – not to the timetable of one conductor's vision. Petrenko is honoring Shostakovich's integrity and inventiveness. He's not trying to fit the music into a public (or personal) mold. This is not to say that he doesn't bring his own qualities to the works. He does. But they start in the score and respect it to the utmost. This also entails a much slower pace than is customary. Particularly they draw out the magical filigree of the end of the Fourth [CD.3 tr.3] and at the start of the Fifth [CD.4 tr.1].

Petrenko's and the RLPO's searching and consumate accounts of the Fifth, Sixth and Eighth ideally display their ability to expose instrumental timbre and characteristics. Focus is fine and finite in all the strings; the brass project sound, not wind; the section never sounds overblown. The woodwinds match delicacy to clarity; and the percussion players use precision to suggest presence, not bombast. Typical of this insistence that instrumentation be pointed and honed, not contribute to an impressionistic blur, is the allegro non troppo section of the Fifth's first movement [CD.4 tr.1] nearly nine minutes in: at first hearing the combination of piano running under growling trombones and oboes with unstoppable tramping may seem crude.

But the further it goes on, the more it can be heard as standing for the wider temperament of the Fifth Symphony, indeed it's consonant with the flavors of the cycle as a whole. The music mixes pain with elation in Petrenko's conception. Such a blend occurs in few other orchestral giants after Mahler. Further, the players convey a dignity bordering on the detached – yet which is entirely appropriate because the phrasing, tempi and sense of structure are so assured and purposeful. As phrases die away, pauses make their point. New themes emerge, they all seem to be coming straight from an overall scheme. Hence the controlled and steady – not breakneck – speed of the Fifth's finale [CD.4 tr.4], perhaps.

The Ninth is paired with the Fifth on the fourth CD. It's usually considered not "slight", but a response to the weight of other's (nineteenth century German) ninth symphonies. Even these performers' approach to it brings out Shostakovich's mildly and pleasantly perverse and playful dismissal of conventionalism. It also suggests substance and a justified place in the cycle – like a course in a meal. For these players the work mildly showcases the instrumental "flavors" of the orchestral sections and soloists – especially woodwind. The second, moderato, movement [CD.4 tr.6] is played as tenderly and gracefully as anything in this cycle. Its performance thus adds weight to the otherwise often not fully-understood Ninth symphony. In fact, Petrenko in his notes emphasizes the fact that Shostakovich was probably lamenting that, although the War was over and "won" (the Ninth was completed in 1945), few things really changed for the Russian people.

To be effective, the first movement of the "Leningrad" [CD.6 tr.1] can't be a mere crescendo depicting only resistance and survival – although clearly such determination is perhaps more central to this than any other of Shostakovich's symphonies. The blockade in 1941 mirrors all such foul losses of life (over one million died). Petrenko and his players have a strong understanding of Shostakovich's symphonic structure; and that understanding os nowhere more starkly displayed than in their performances of both the Sixth and Seventh Symphonies. The music always seems to be traveling somewhere; if it weren's we would only be dealing with a static memorial.

Of course the (first movement of the) Seventh needs to "build". But both here [CD.6 tr.1] and in the last movement of the Sixth [CD.5 tr.3], there is great purpose. And it's purpose which doesn't remotely sacrifice the beauty of Shostakovich's writing. In some ways, the RLPO's and Petrenko's Seventh sums up their approach at the half way point through the cycle: it has confidence; it has all the necessary technical prowess; majesty without undue pomp; it pays out the music in architectural splendor without losing either delicacy or the elegant beauty of the writing. Above all, it quietly presents the very essence of Shostakovich's symphonic thinking in the dark years at the start of the Second World War. Elevated though you are by the end of 80 minutes of superb symphonic playing, Petrenko seems to be inviting you to wonder what's next. And indeed, you will not be let down.

In their account of the Eighth and Tenth, the sinuous, reflective beauty of Shostakovich's orchestral writing is again to the fore. The moods, sounds, play of light and shade in the slower passages are striking and get pride of place every time. Emphasized in integrated fashion too are such potentially "insistent" moments as the third movement allegro non troppo [CD.7 tr.3] in the earlier work; and fiery condemnation of Stalin in the Tenth's second allegro movement [CD.8 tr.2]. Again this is not to say that the teeth are drawn of the ferocity of the writing. Rather, that the fire is contextualized. The music is not spectacle; it's situated in the series. For when the quiet returns after the storm, it's never a degradation or anti-climax. But as much a part of the work as was the preceding "excitement". Indeed, the build up – in the Tenth's taut first moderato movement [CD.8 tr.1], for example – to such climacterics are as much part of the music as the "fireworks" themselves.

The Eleventh [CD.9] is subtitled "The Year 1905"; the composer's grandfather was a hero to him, a real revolutionary who took part in the storming of the Winter Palace. Much has been written, of course, about the extent to which actual historical events "appear" in the music… the Eleventh was written at the time of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, for instance. It's probably wiser to see this – as much of Shostakovich's writing – as a broader, general critique of the intolerance of a State when its people are dissatisfied. Again Petrenko and his forces happily and successfully work with that abstraction, and not a particular political or local saw in mind. By the time you've reached this Symphony in the cycle, you'll have come to expect power, drive, precision and projection along with Petrenko's phlegmatic light touch and attention to all musical details. Here grandeur is added… listen to the push of the march in the second ("Ninth of January") movement [CD.9 tr.2]. Splendid because the rhythms and dynamics derive from the music itself, not an external narrative.

The Twelfth Symphony, written almost five years later (1961), is also ostensibly named to recall events in the composer's country's history, "The Year 1917". For all the scope for rhetoric, one senses that Shostakovich had become mellower and more resigned by this point in the cycle. The performance reflects this: it's (correspondingly) more introverted, reflective, dour, slower, sadder. Though it never lacks energy or pulse. But is justly more subdued. Once more a new characteristic of this set is aded: conscious sobriety. At the same time, a corner has been turned: the last three Symphonies are different.

The Thirteenth, "Babi Yar", was written in the next year. It's the first to include singers again since the Third. Alexander Vinogradov's bass is superb – his intonation, commitment and projection have just the right amount of detached sardonic scorn; yet are clear. They ultimately evoke a musical and lyrical response as much as a worldly one. One might have reservations over the clarity, diction, and miking even, of the Huddersfield Choral Society and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir here. A little fuzzy. At the same time – one hears it particularly towards the very end of the fragile fifth, allegretto, movement – Petrenko's RLPO displays tenderness, passion and almost comfort instead, perhaps, of an easier downright resignation. This is perhaps a Slavic strength. It's highly effective.

The Fourteenth, written eight years later (actually the longest gap between any two of his symphonies), again has Vinogradov with Gal James (soprano). Again the singing is clear, trenchant and affecting. Both singers curve and delve into the lyrical lines and negotiate the sardonic runs and passings which express – with the exception of the Kuchelbecker setting, "Delvig" – total despair and nihilism… Shostakovich knew his mortality more closely than ever before, having survived a heart attack. Petrenko considers it the composer's greatest work. Perhaps not least because he can relate to Shostakovich's implicit insistence that art must be allowed (obliged, even) to survive beyond death.

When Shostakovich introduced the work in June 1969 he alluded to Mussorgsky "… [it's] a great protest against death and a reminder to live one's life honestly, nobly, decently, never committing base acts&helli; [Death] awaits all of us. I don't see anything good about such an end to our lives and this is what I'm trying to convey in this work." One might extend that sentiment and say that Petrenko faces just such a task: does he add and/or use audible anger, resignation, serenity, clarity, despair, and indifference so as to convey the force with which Shostakovich had and had not made his peace? In fact, his forces tether the well-integrated performance to the essence of Shostakovich's ambivalence. Listen, for example, to the the intimate yet lively Apollinaire setting, "On Watch" [CD.11 tr.5] where mischief and a motif vaguely redolent of the Totentantz vie with those tears that only come from the laughter of hopelessness to suggest a reaction to all pointlessness, not this particular pointlessness. Such detachment suits the music and its intentions very well.

It's perhaps by now that the listener who had expected a searing, brassy, wailing or a militant, marching purely ironic Shostakovich will see how Petrenko's conception and execution are far more subtle, authentic and ultimately far more satisfying. For they achieve a balance which returns time and again to the soul of the orchestral and instrumental object, not the symphonies as political or personal commentary (although clearly they were written – and exist for us – in these familiar contexts). Yes, Shostakovich wrote in the world – just as Mahler aimed to encapsulate the universe in his symphonies – but he used music to place music in the world, not to suggest references to the world. The dynamic, the shadowy, quiet passages of the Fourteenth ("The death of the poet" [CD.11 tr.10], for instance, which for Petrenko is almost operatic in scale) make this point well: as this movement slides almost without notice into the brief, pungent two dozen words of the "Conclusion" (of Rilke), the music as conscious artistic creation will last after external allusions or glosses have faded.

Shostakovich's final Symphony, the Fifteenth, dates from 1971, only a few years before his death. In fine Shostakovich's eloquence needed no words; this is a purely orchestral essay of barely 45 minutes consciously alternating slow and fast movements and sections (the second and fourth have three and four such internal alternations of tempo each). It famously contains quotations from Götterdämmerung and William Tell, which confused and puzzled when the symphony appeared. It would be possible for a conductor to content themself with allowing the mélange (which also includes nods to Mahler's Fourth, as well as self-quotation by the composer) to stand for something supplied by a knowledgeable audience. Not in this case. Petrenko is aware that – perhaps like the suppressed joviality of the very last chamber works of Beethoven – Shostakovich had already seen past death. He conceived a lot of the Fifteenth in hospital. Petrenko lets the orchestra tend towards the indeterminate (the "disentanglements" of the first movement allegretto [CD.2 tr.4] hint at playfulness, for instance). Yet it is the playfulness of someone happy in their own nightmare. The second movement halts, splutters and falters like no other recording. A final sign, perhaps, that Petrenko has seen other dimensions in Shostakovich's works than many other interpreters. Yet it's all integral to the music. Instruments (pizzicato strings, for instance) voice their concerns. And lead to the final doleful passage when – perhaps somewhat unexpectedly: Petrenko hints as something more until the last – Shostakovich quietly, wistfully, regretfully, closes his account with the symphonic world.

The acoustic of the aforementioned Liverpool Philharmonic Hall is grand without being too resonant; yet strangely intimate and supportive of a full projection of orchestral color. This is well for the composer, soloists and each section of the Orchestra… no nuance is missed. Gradations between tutti and smaller-scale passages are maintained and the music is heard at its distinct best. The 50+ page booklet explores each symphony in chronological order through Petrenko's own words as contained in a series of interviews for the BBC Music Magazine with its former editor, Helen Wallace. It's particularly illuminating as a commentary on Shostakovich's musical and personal life, the symphonies, and the relationships between all three. The booklet also contains all the texts of the choral and vocal symphonies (2, 3, 13, 14) in transliterated Russian and English.

These Symphonies are, of course, megaliths of the last century's orchestral repertoire. Of the non-Russian cycles (consider Gergiev on the Mariinsky label for an all-Russian cycle), Petrenko's and the RLPO's must now be considered the reference set. They have the depth, integrity, balance, musicality, interpretative intelligence, technical aplomb and sheer love of Shostakovich's developing musical story to grant them that status. Thoroughly recommended in every way.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey