The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Ives Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

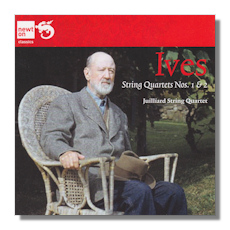

Charles Ives

String Quartets

- Quartet for Strings #1 "From the Salvation Army"

- Quartet for Strings #2

Juilliard Quartet

Newton Classics 8802197

It's something of a pity that Charles Ives, given his importance in musical history – especially for tonal and rhythmic innovation – does not receive more attention in concert programming and recordings. There are half a dozen or so other recordings of the composer's two string quartets. Although this one from the Juilliard Quartet on Newton Classics is in good company, it stands out over the others available for the performances' faithfulness to the spirit of Ives, and the animated yet never overly excitable playing. This is a reissue of the recordings made for Sony at their Columbia 30th Street studio in New York as long ago as 1966/1967 (three takes: two for the First Quartet and one for the Second) when the lineup was Robert Mann and Earl Carlyss (violins), Raphael Hillyer (viola) and Claus Adam (cello).

The first Quartet, "From the Salvation Army", was composed at the very end of the century – between 1897 and 1900. It contains themes from organ music which Ives had been playing at church since a child. Typical of the composer. Yet in styles that at times resemble diluted late Beethoven and even earlier composers of stately canon. It doesn't lack life. But tends to the expository as much as the intrepid. So the Juilliards' measured and dignified style with a blend of sweetness and stillness certainly reveals the music in the best light. By undemonstrative, yet lively though well-paced, playing full of direction they seem to be quietly helping Ives sidestep potential challenges of derivativeness. Listen to the blend of pizzicato and chordal writing in the third movement adagio [tr.3], for instance: climaxes and changes in tempo and dynamic especially in the second half of the seven-minute-long movement are given point and purpose. Our interest is maintained as Ives' handling of melody unfolds in linear fashion.

The second Quartet is very different – although written fewer than 15 years later. It's much more sharply pointed, atonal; it forges new sounds for the medium and is more evidently the Ives we know. What links the two approaches by the Juilliards is empathy… a warmth, tenderness almost. Certainly a significant accord with what Ives achieved in the work. Although the first Quartet's fourth movement allegro marziale strays into the world of ambiguous tonality, it's always centered in a way that the second Quartet's tonality is often not. Their playing is also unassumingly authoritative. One knows for sure from the very first note that one is in good hands with the Juilliards. This is music which they have totally internalized, which they understand, and which is all their own. Although it's played with a breadth and generosity which suggest it's been happily loaned by the composer, rather than snatched from his often idiosyncratic grasp.

The more nervy, possibly more substantial, certainly more "pushy", "edgy" qualities of the second Quartet offer the players opportunities to present Ives' quiet adventurousness in just the light it needs: Yes, the tonality shifts and invites our closer attention than has to be the case with the earlier work. Yes, one thinks of Schoenberg's Second Quartet, written around the same time (1908), especially during Ives' Second Quartet's third, and final, movement adagio [tr.7]. But the music is quite content to be what it is for its own sake. Nowhere is this more evident in the Juilliards' playing than at the quiet (but not fully-resolved) end of the Second Quartet's final movement.

In the case of both the First and Second Quartets the Juilliards seem to have taken to heart Ives own description of the medium which draws on Goethe's that it's "four rational people conversing" as for "…four men (sic) – who converse, discuss, argue (in re "Politick"), fight, shake hands, shut up – then walk up the mountain side to view the firmament". Yet at the same time, the players are aware that conversations end, discussions do reach conclusions. There is a global conception and import of the music. Their strength as an ensemble is this blend between being involved with the music's progression and very reliably directing it.

Given the age of these recordings (nearly 50 years; Ives had only died a dozen years before, in 1954) the acoustic is remarkably good. Understandably the dynamic range is less than it would be for a digital recording. But there is a minimal, helpful, resonance; and a clarity of each instrument's register and projection which really put the musical experience first. The recording is close. Again, this is a benefit: the music is presented as if the listener were there. Yet is not in any way cloying. The slim booklet contains but two and a half pages on the music, though that's a useful introduction for anyone unfamiliar with this captivating music. Lovers of Ives who do not already own the String Quartets (the Leipzig Quartet's survey of these two Quartets plus the two Largo risoluto works, A Set of Short Pieces and Halloween for String Quartet and Piano on MD&G (Darbinghaus & Grimm) Gold MDG3071143-2 is a good alternative) will be happy with these recordings – even though this CD lasts under 50 minutes. For nuance, insight and overall transparent yet persuasive accounts of music that deserves to be better known, this classic account by the Juilliards is recommended without hesitation.

Copyright © 2013, Mark Sealey